“A house is the shell of a home,”[1] as Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa told us in his 2017 book Habitar.

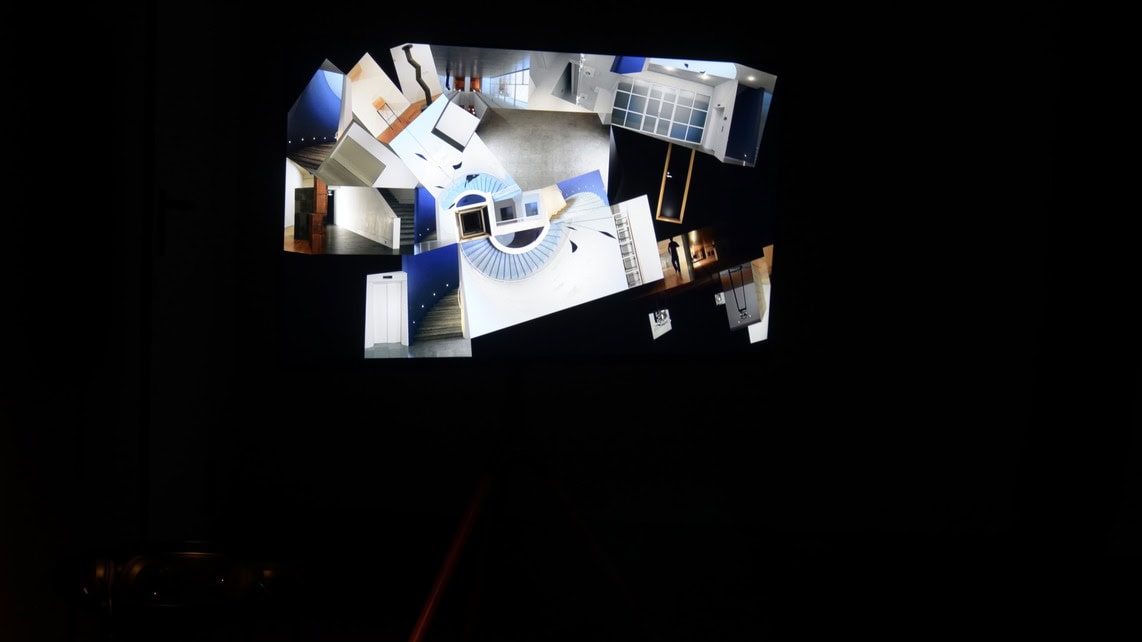

When faced with Patrícia Garrido’s installation at Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes, and in keeping with the exhibition’s name Casas (Houses), the observer tries to find a place to walk through and comfortably enjoy. A sense of dwelling, of interior, of shelter. But we find ourselves at a crossroads, consisting of a set of angle brackets, an assemblage of extensive metal elements stretching out in a maze-like pattern and intersecting throughout the gallery floor, preventing the visitor from feeling the wholeness of an inhabited area.

This sense of relinquishing the idea of home, which Garrido’s metal elements apparently suggest, grows stronger as more gutters are spotted and as the uneven connections between them are noticed. Made up of four supports or foundations, the structures initiate an uninterrupted dance of intertwining straight, perpendicular, parallel and oblique lines, not hard to equate with city streets and thoroughfares, defined by their unpredictability. These free associations may be immediate. A countless array of bridges, motorways and buildings, with their unexpected shapes and angles, throb in the imagination as we travel through the site.

An idea of home, or a place offering privacy, a haven away from the city, or even somewhere safe, is what we strive for. But Garrido’s installation never provides a comfortable experience.

Whenever one thinks that a cohesive area may emerge, a centre where our eyes and notion of home could rest, another sharp edge pops up, another unexpected corner cutting through and disturbing us. It leaves us with a lingering feeling of exclusion, despondency and of not belonging to any place.

The artist’s vision of a built location is not based on the rhythms, areas and silences that an architect usually deals with, but rather on the mental construction of images, on the underlying nature of a house[2].

Pallasmaa explains that the artist “is not interested in architectural principles and formal intentions and, as a result, is directly concerned with the mental meaning of the images of a house and home. Artistic works that deal with space, light, and buildings and dwellings can offer architects important lessons on the very essence of architecture”.

For instance, the painter “creates an imagined house on the canvas”[3], which may be the outcome of a range of emotions and sensations: sometimes protection, order and joy, while at other occasions confusion, rejection, loneliness and sadness.

Garrido’s structures also appear to be coated in memories. Of modernity, the avant-garde and its myths.

Who can fail to recall Rosalind Krauss’s remarks on the exclusive visuality of the visual arts?

In the “spatial sense, the grid establishes art’s autonomy”[4], distancing it from discourse and words.

In her text Grids[5], Krauss points out that, in the spatial sense, there is a distancing from nature.

In Garrido’s installation, the structures ripple between order and chaos, movement and static geometry. Antimimetic and unnatural dimensions surface.

The Casas exhibition follows on from Patrícia Garrido’s work, which, according to João Pinharanda in the exhibition’s supporting text, has been dotted with memories and fictions from her own life. Her work frequently features visual labyrinths and intellectual, geometric-mathematical games.

This exhibition, a project run by the Carmona e Costa Foundation and coordinated by Patrícia Garrido and Manuel Costa Cabral, will be at Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes until June 1, 2024.

[1] Pallasmaa, J. (2017). Habitar. Editorial Gustavo Gili.

[2] Ibidem, p. 19.

[3] Ibidem.

[4] Krauss, R. E. (1986). The Originality of the Avan-Garde and Other Modern Myths. The MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England.

[5] Ibidem.