The most recent temporary exhibition at the Museu Nacional do Azulejo fills three venues. But, to be more precise, it also covers the permanent collection. A grey caption tells us that the works, which we can visit at any time in the museum, are also part of this narrative. This is a sort of peddy paper, calling for our active attention. Like the pictorial medium of the tile itself, the aim is to camouflage, adapt, reshape itself.

We start on the ground floor, where Sombra de Convite by Lourdes Castro takes us into the room. A formal borrowing from the nineteenth century invitation figures, presented here in a contemporary language. One of the possible perspectives of this show, at a converging point between several works, is this rearrangement of old references through a new and uncluttered look. Another example is found at the back of this first room, in a panel by the Hungarian-Portuguese Hansi Stäel, where we revisit the pictorial motif of the diamond pattern, typical of the tiles of the first half of the seventeenth century, through a pointillist approach. This tile motif was first produced in Spanish potteries and then imported to Portugal (which began to develop its production later) during the Spanish annexation of Portugal. This act of importing a foreign motif, meanwhile naturalised, is relevant when we consider that it was the pattern chosen by Hansi Stäel to pictorially reformulate when she settled in Portugal between 1946 and 1957.

The most interesting point of convergence, perpendicular to this, evident not only in contemporary production, but in the history of tile production, was when ceramics transfigured itself into other pictorial media, often lying to us, convincing us that it is something that it is not. We see a manifestation of such in Cecília de Sousa’s work, especially in Placa Cerâmica from 1991 where faience becomes granite, and traces draw the outline of an imaginary place. In Graziela Albino’s work, shown on the first floor, a dish in modelled faience masquerades as cork. This dialogue between media collides fatally in Cândida Wigan’s efforts, where the artist applies textile patterns to the tile’s ceramic plate, as if it were a printed sheet.

The dialogue between tile and textile is unavoidable since its origins in the 16th century. Although Cândida Wigan’s work is the consequence of an avant-garde, and profoundly contemporary, reformulation, tapestry has always existed not only as a model, with tile often being its substitute for practical reasons, but also as a kind of ghost, given the large size of the two media, as well as their roles as coverings. Some of the contemporary tiles we see here revive that path. For instance, the tile panel by Bela Silva, made up of a framing where surreal, comic, shapeless figurations dwell, as well as references to decorative motifs, such as shell-shapes from the rococo aesthetic. We also find a set of large panels, “tile carpets” such as the delightfully cerebral Presente by Catarina Rita and Almeida Negreiros, composed of kinetic modules, reliefs like two-tone painted tiles. They elicit an illusion of movement as we walk through it – only at a distance do we see that these tonal combinations make up one word: “present”, as if it were a self-conscious act. We also highlight the decision to exhibit experimental works in tile production. Among them, the beautiful untitled compositions by Ana Hatherly, made in the artist’s last years, when she sought to explore graffiti as a pictorial possibility.

There are essential names of Portuguese art: Maria Keil, Vieira da Silva, Fernanda Fragateiro, Menez, even Joana Vasconcelos, all mandatory in an exhibition that wants to document the female pathways of contemporary ceramics. But pertinent names are missing. The most obvious is the Brazilian Adriana Varejão, who not only works with a post-colonial reading of the Portuguese tile in her country, but is also one of the most recognised artists in this current pictorial medium. This would give the exhibition and the museum collection a problematising layer to healthily reconsider historical narratives of the museum institution itself. But this inclusion would imply a more inclusive and comprehensive alteration of the exhibition’s title.

But if we bear in mind the curatorial aspect, this is the exhibition’s weak point: although museography is appropriate with ceramic objects, tiles or archive documents, there is no narrative persuasion that allows us to look at the displayed objects from new angles. On the contrary, there is an agglomeration of important works that are somewhat closed in on themselves, apart from the aforementioned Presente by Catarina Rita and Almeida Negreiros. This kind of inconclusiveness is also visible in the exhibition’s signage. We do not know exactly which rooms are from the temporary exhibition. The vaguely arranged texts do not indicate whether they belong to the same exhibition. We can only tell if we read the works’ captions, descriptions or poem excerpts. The first text of the exhibition states that these will be visible throughout the show. Be that as it may, the exhibition’s inclusion in the permanent collection solves this problem cleverly. It proves that female representation has always been a concern of the institution, while inviting us to discover the museum’s other spaces.

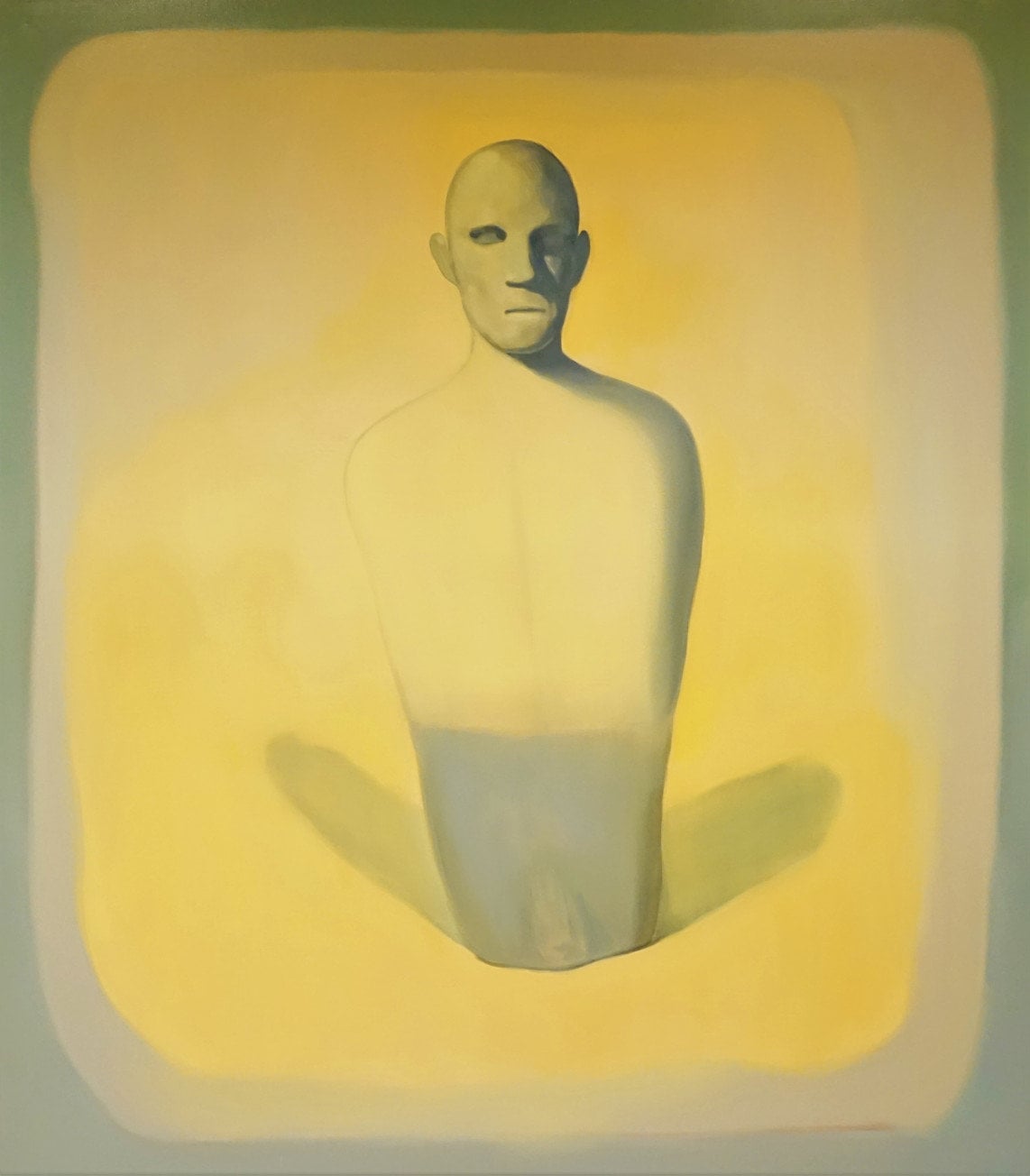

We should highlight some less well-known, but also important, names present here: the religious painting by Estrela Faria, with tiles in symmetrical, hypnotic compositions. The figuration is reminiscent of the austerity, emotionally intensified, of Byzantine icons, or the ceramic possibilities of Maria Manuela Madureira in her Auto-retrato in moulded faience, with a cubist tendency, somewhere between Picasso and Rosa Ramalho.

This is a qualified exhibition to uncover the opportunities of a pictorial medium that is sometimes pushed into the background, as well as the role of women artists in reshaping their contemporary imaginary. They created new pluralities for a more comprehensive and democratic understanding of Portugal’s art history.

Territórios Desconhecidos: A criatividade das mulheres na cerâmica moderna e contemporânea portuguesa (1950-2020) is at Museu Nacional do Azulejo until June 26.