article

Inhabiting an impossibility: Estaleiro Almada/Orozco by José André and Patrícia Portela

In Estaleiro Almada/Orozco, Patrícia Portela and José André bring together two coordinates: alongside artistic languages (installation and performance), there is also a dual geography (Portugal and Mexico). They question social realities and the power of tradition through the pictorial motifs of José de Almada Negreiros and José Clemente Orozco.

At issue are the panels at the Gare Marítima de Alcântara, by the Portuguese painter, and the frescoes by the Mexican muralist at the Museo Cabañas in Guadalajara, a former hospice. On this side of the Atlantic – from where ships first departed and later welcomed first-class tourists to the only tourist destination of choice in Europe. On the other side, on the continent that would come to be called America – a place of killings, looting, fire, blood, crucifixes, armour and frightening rituals, upon the arrival of the so-called ‘Conquistadors’.

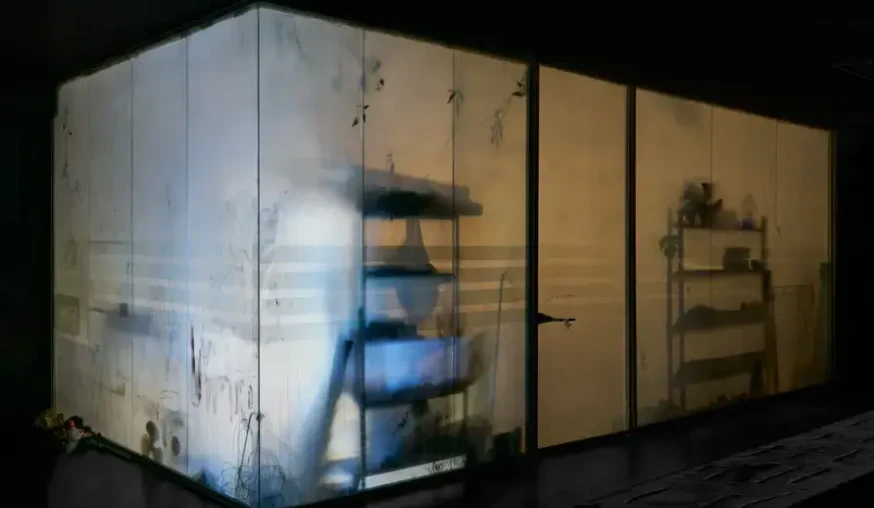

Upon entering the Appleton gallery, visitors are greeted by three screens in the room. The images are a mixture of scenes depicted in these two murals: a two-headed horse, boats, sails and amalgamated bodies, possibly a unicorn, unwrapped in a cloud of thick black smoke. Each image is transformed into another, making it impossible to distinguish the original or any certainty. The elusive territory of the digital installation surprises, both with amazement and alacrity, wandering through the vibrant colours, the yellows, blues and reds of the chosen paintings. José André (half of the duo Irmã Lúcia – special effects, who has worked, for example, with directors Pedro Costa, Gabriel Abrantes, and João Botelho) and Portela, creating interdependent images and text, reconfigure the two distinct imaginaries of the painters Almada and Orozco. It should also be mentioned that André and Portela, long-time collaborators, had already worked together on projects where painting is the raw material, such as the performance Parasomnia (presented at Mãe d'Água das Amoreiras, 2019, and included in the programme of the Teatro do Bairro Alto).

Next, in Patrícia Portela's lecture (the italics in this text are quotations), a gallery of characters with whom she dialogues parades by: a special travelling companion, a kind of fairy godmother (sharp-tongued and inquisitive), that is, Dúvida, as she is named; Odília, a confused muse; Pedro Álvares Cabral; Júlio Dantes (precisely, the one from Almada's manifesto); Duarte Pacheco; Michelangelo; the Countess of Alba; the chairs of Duchamp and Salazar; Alexandre O'Neill; the ship Catrineta; Pero Vaz de Caminha; the strapping young men with their fine physiques; the girl so well-formed, so round, and her shame, oh, so graceful; Bartolomeu Dias; Stanley Kubrick; the yellow Adidas trainers; the secondary school teacher; the crying child; the breastfeeding mother; José Mário Branco; António Câmara; Santa Rita Pintor; Tristan Tzara; a Pessoa; a Donald Trump, ….

The writer's rhythmic, inventive and radiant enunciation faces an impossibility. To merge, in a third place, a corridor, Almada projecting on one side and Orozco projecting on the other: a central space where two or more realities would coexist simultaneously. At the nerve centre, the viewer would be three contemporary people (neither this, nor that, nor witness), but bringing together the ability to feel and understand various times in the continuum of history and its problematisation. If the departure was a promise, the destination will be an atrocity. In fact, these intentions are often reproduced, as are neocolonialism, racism and fascism, which are daily and transversal.

And, besides the impossibility, another question arises in Portela. When visiting the panels at Gare Marítima today, she is assailed by doubt. Incisive and questioning. When we look at something with fresh eyes, we may lose a great love. The confessed Almada enthusiast finds herself wondering. Portela confronts Almada. Who, after all, are these people in the scenes? What laughter comes from these settings? What strength and what cry did Almada imprint on these panels? Wielding arguments with Doubt, she concludes that the painter does not shy away from portraying the lives of the poor during the Estado Novo, but does little to elevate or save them. An inadequate denunciation. But that is not enough. Let us take a step back.

And she distributes barbs for all tastes (a nod to the satire of two other figures – Eça and Ortigão). Rewinding aspects of history, searching for such a tiny Portuguese identity, we come across the Letter from Pero Vaz de Caminha in Vera Cruz: the audacity of thinking that a country is being founded, and for oneself. And also today's schools, where nothing more than crystallised models are taught, places where violence among young people is not addressed, so that parents can continue to exploit them for labour.

We live to maintain the fraud, to maintain the script. Reasonableness and humanly shared urgency are thrown to the wind.

The artist's two characteristic modes, landscape and narrative, intertwine in a proposition: Portela requires both artistry and humanisation from an artist.

Perhaps inhabiting is not a matter of levity, but neither is it a matter of force. The Portuguese narrative – small people, not rocking the boat, asking favours of despots, of any state or era – smacks of farce. The tragic fado of the Portuguese soul is neither comedy nor tragedy.

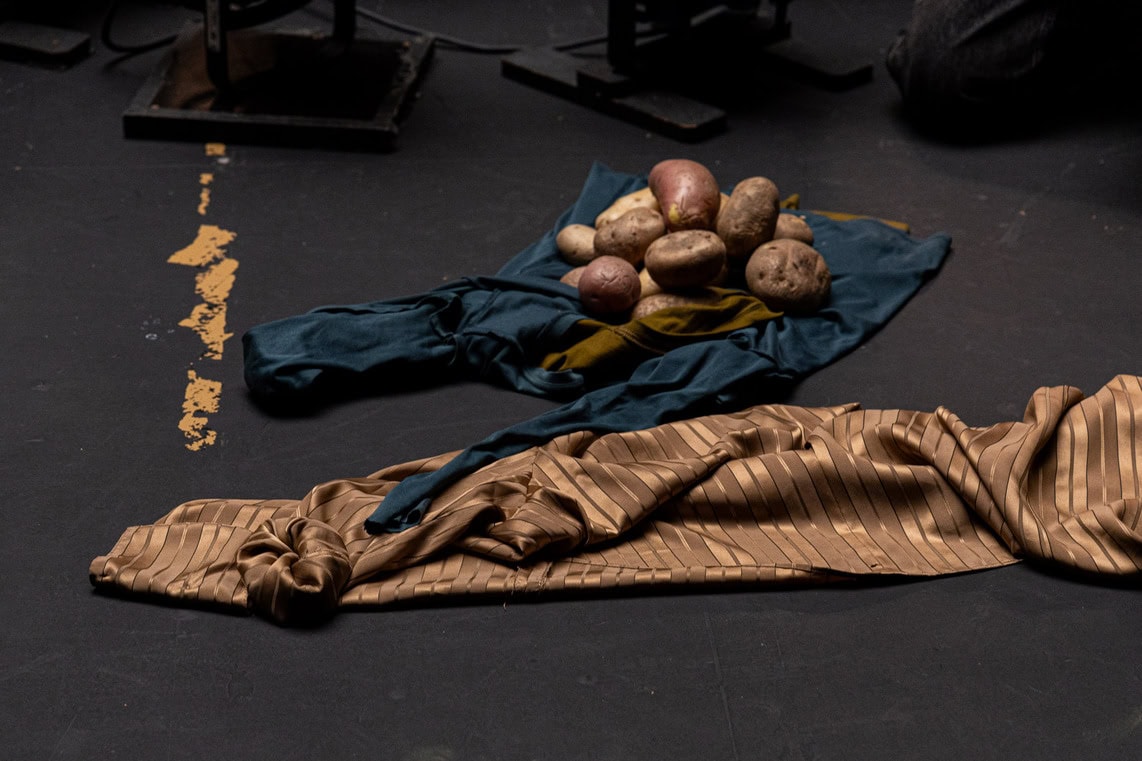

Perhaps, in its own way, Portela is seeking to eliminate tradition, as did the artistic manifestos of the last century (even so, not even these escape the scrutiny of the writer, who quotes with disdain: We want to glorify war, militarism, patriotism, (...) and contempt for women). Let us recreate the spirit of the time – with our everyday bodies, like the fishmongers at the Gare Marítima – because this is, after all and always, a clash. Yes, let us put our finger on the wound. And so, what is the power of an artist, and how can it be used? Orozco in blood and fire, Almada in fearful melancholy. With hammer and brush: the icon, the space, the word.

The show was presented at the Appleton Gallery on 24 and 25 October 2025, as part of the Festival Temps d'Image programme.

BIOGRAPHY

António Figueiredo Marques writes essays, exhibition texts and articles on the performing arts, combining artistic and theoretical components. He reflects on dramaturgical editing and modes of scenic composition, studying the visual, sound, body and intermediate dimensions of contemporary performance. He is a researcher at ICNOVA, has a PhD in Communication and Arts (NOVA FCSH) and is co-editor of the website on performing arts and expanded performativities CRATERA | Performance & Cognition. As a performer, he regularly trains with Mónica Calle, Yael Karavan, Renato Ferracini, Miguel Moreira, Tiago Vieira, Jorge Silva Melo, Miguel Loureiro, among others.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

10 Nov 2025

Nem pena nem paixão: Paulo Serra at Salto

By Dela Christin Miessen

Next

article

13 Nov 2025

To stage is to love: to love and devour, by Tolia Astakhishvili

By Tomás Saraiva

Related Posts