article

Histórias lindas de morrer, by Sofia Saleme

“Sofia Saleme works between the intimate and the clinical, the beautiful and the object, the visible and the elusive. The exhibition does not romanticise pain, but observes it, names it, and covers it in gold. Histórias lindas de morrer does not address the end, but rather continuity.”

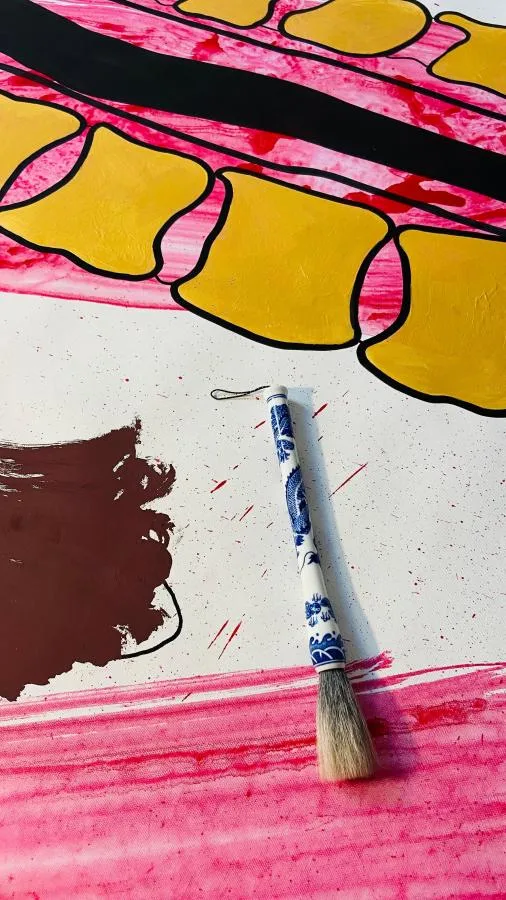

In the former anatomy laboratory of the National Museum of Natural History and Science in Lisbon, Sofia Saleme installs Histórias lindas de morrer. The exhibition transforms the body into a surface for observation and the formerly clinical space into a place of symbolic healing. Comprising ten vertical canvases suspended in the Branca Edmée Marques room, it invites visitors to confront what the body remembers: wounds, matter, and what remains, scars.

Saleme approaches space with the same rigour with which she observes the body. She measures, draws, and translates its entrails, transforming the artistic gesture into an exercise in recognising what is imperfect, vulnerable, and vital. Drawing is her native language, the point of contact between the physical and the symbolic.

The artist, born in São Paulo in 1989 and now dividing her life between Lisbon and São Paulo, proposes a simple and effective gesture: replacing the exhibition leaflet with a pharmaceutical leaflet. ‘Read this leaflet carefully before ingesting the Histórias lindas de morrer’, it reads. The irony returns the role of patient to the public and the function of diagnosis through reflection to art. The museum is transformed into a symbolic consulting room where each painting acts as a symptom, a remedy, or a relapse.

The materials reinforce this idea of repair. By using natural Japanese pigments, such as gofun, a white pigment extracted from oyster shells, and gold leaf applied to the canvas as if covering a scar, the artist emphasises the importance and beauty of the body marked by time. Here, gold does not appear as a metaphor for triumph, but for acceptance. By using techniques associated with the Wabi-Sabi philosophy, Saleme values imperfection and vulnerability as aesthetic material, for example, in works such as Céu Estrelado or Pústula Ouro the body is treated as a territory of memory and transformation, and what is uncomfortable or rejected, such as wounds, pus, fat or ageing, is covered with gold and transformed into a precious scar. The gesture is intimate, almost ritualistic, and reflects an attempt to reconcile what society tends to hide.

The titles of the works, Peso do Invisível, Compulsão Prazerosa, Arrepio e Entre o Pus e o Ouro, are reminiscent of medical diagnoses hand in hand with poetry. They function as mirrors of what cannot be seen but can be felt, of what is part of our memory and our body, where the latter takes on the role of an archive through its imperfections.

There is a clear parallel between the works and the space where they are found. The museum, which houses the Cuidar e Curar (Care and Cure) collection, linked to the Faculty of Medicine, becomes an accomplice in this dialogue between art and anatomy, between cure and disease. Sofia Marçal's curatorship emphasises this relationship between art and science. By choosing the former anatomy laboratory and integrating it into the museum context, the curator transforms the space into a conceptual extension of the work.

The body, which was previously an object of study, becomes here a territory of reflection and memory. Sofia Saleme works between the intimate and the clinical, the beautiful and the object, the visible and the elusive. The exhibition does not romanticise pain, but observes it, names it, and covers it in gold. Histórias lindas de morrer does not address the end, but rather continuity. It is an exhibition about what remains after the wound and about the capacity of art, like the body, to accept itself from what hurts.

Histórias lindas de morrer, by Sofia Saleme, is curated by Sofia Marçal, at the National Museum of Natural History and Science, in Lisbon, and can be visited until 6 January 2026.

BIOGRAPHY

Bárbara Braga has a degree in Art History and is in her second year of a Master's degree in Curatorial Studies at the Faculty of Arts of the University of Coimbra. She conducts research and writes critically in the field of contemporary art.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

28 Dec 2025

Terra Sol Liberdade, at the Casa de Arqueologia e Artes de Beja

By Carla Carbone

Next

article

05 Jan 2026

Dois Stereos, by João Pimenta Gomes

By Mariana Machado

Related Posts