article

Notes on a finished photography

"Jeff Wall's work has always been anchored in reality, refusing fiction to define it. The artist explains that all the images are born out of real situations and are therefore closer to documentaries and have no pictorialist ambitions, even when they are inspired by literature. He rejects amateurism, not only as a form of representation, but also as an aesthetic essential to photography".

I couldn't help but take advantage of the occasion provided by one of Jeff Wall's largest exhibitions to date – which occupies the entire Maat building with an impressive number of works (despite the absence of some classics), especially when coupled with the recent release in Portuguese of his Escritos sobre Arte (Writings on Art) – a clear demonstration of the persistent importance of the theoretical discourse that underpins his work – to revisit a question recently raised by Dorrell Merritt in ArtReview[i], on the occasion of another major exhibition by the artist at the White Cube – but which has already been widely discussed over the last two decades: is there a future for Tableau photography?

I would like to point out that the word "finished" (in the title) does not in itself suggest that Jeff Wall's work is obsolete. Rather, it refers to his conscious approach to the photographic image as a final, stabilized construction, the result of a controlled process of staging, production, and post-production, which culminates in a single, definitive object (what is exhibited), with any transition to another medium becoming a reproduction, just like a painting. This conception of the image as a single, stabilized artifact is central to tableau photography, but it doesn't end there.

Far from seeking a generalization that reduces the Canadian artist's work to the “mode of presentation” of his photographs, it is difficult not to approach him, when he – among the other "usual suspects" such as Sherman, Struth or Gursky – is a central, almost canonical figure in that way of operating that played a decisive role in the emancipation of photography as "art” from the 1980s onwards, opening doors to institutional interest and raising new questions and ambitions for the medium.

The recognition that Jeff Wall's work enjoys, particularly in the art market, is largely because his photography shares art logics not associated with this medium, such as uniqueness, monumentality, and scarcity. This decision implied a departure from the qualities historically associated with photography, such as accessibility and reproducibility, to which are now added others, perhaps more difficult to pin down, such as the fluidity and fragmentation that define contemporary visual culture.

Moving away from the argument that art is obsolete – a criterion that only applies to "bad art”[ii] – I'm interested in thinking about whether it has lost its ability to problematize the way photography is exhibited. And even more so, if it continues to depend on photographic practice to exist as a language.

Jeff Wall's work has always been anchored in reality, refusing fiction to define it. The artist explains that all the images are born out of real situations and are therefore closer to documentaries and have no pictorialist ambitions, even when they are inspired by literature. He rejects amateurism, not only as a form of representation, but also as an aesthetic essential to photography – a central position of the famous essay Marks of Indifference[iii]. He argues, like Michael Fried, that this stance, as well as the existence of an original, culminates in an approximation or elevation of photography to the status of autonomous art, close to painting and sculpture. It's not a question of "using" photography, but of making photography, with the artist being a full operator of the process and its intentions. This legitimization has been true, even commercially.

However, a genre that imitates reality, as opposed to spontaneity, error, or gesture, may find here, along with other issues, similarities with the modus operandi of a rising technology: artificial intelligence.

I don't want to jump to conclusions because, at the time of writing, AI may not yet have the capacity to "imitate" to this extent. Still, I do not doubt that this capacity will soon come.

Wall is certainly more restrained in his detachment from reality than other photographers in the genre, such as Gregory Crewdson, and, in my opinion, also more interesting. However, when we look at this sample of images at MAAT, we realize that the photographs from the last decade tend to be more stylized, formal, and rigorous, with greater dramatic restraint than the previous ones. I believe they can be considered less documentary, sometimes breaking the "unified image", as in Informant (2023), where the overlapping is reminiscent of a digital device aesthetic, sometimes giving space to the narrative and introducing doubles in a Gurskian exercise, as in The Gardens, the huge triptych featured in the exhibition.

If this flexibility with reality exists more and more vehemently and if the viewer doesn't seem to be affected by this distancing, is it possible to admit that the way the image is presented has become more decisive than the way it was made? The strength of Wall's images – and tableau photography in general – lies less in their fidelity to an observed reality and more in the way they impose themselves as constructed images. Its impact is the result of an exhibition device that demands attention, scale, uniqueness, and permanence. In this sense, this distinction between documentary and fiction becomes less relevant than the way each photograph behaves in the exhibition space – this is the essential space of the genre and the form that brings it closer to painting or sculpture, as Fried proposed.

If the mode of presentation overrides the mode of production – and if the authority of the image depends more on its form and institutional inscription than on its fidelity to reality – then perhaps it's not absurd to ask: if an AI-generated image is constructed and presented under the same exhibition regime, can it provoke the same aesthetic experience? And if so, will it no longer depend on traditional modes of photography to exist? Because with the evolution of AI, through training from millions of images, this problem is expected to be purely conceptual – something that will never cease to be a question for Jeff Wall.

In 2009, in an interview with Aperture[iv], Michael Fried criticized Gursky for crossing the line that makes photography his business. This is followed by an important question: "Wouldn't it be interesting if, in a future digital age, the idea that photography is an 'index' or a drawing of light ceased to have great relevance?". To which he replied: "That would be interesting. But what isn't clear is what the very concept of photography and the photographic might mean under these conditions. It could be the evolution of a set of technological procedures to produce large, flat, and 'representative' artifacts for observation. But would viewers begin to feel that these artifacts are no longer photographs? And if they didn't feel that, would it matter to them? I have no idea.". Perhaps the time has come to answer this question in Tableau, of course. I believe that documentary photography has other solutions.

The Jeff Wall exhibition, Time Still Stands. Photographs 1980-2023, curated by Sérgio Mah, is on show at MAAT until September 1, 2025.

[i] Merritt, Dorrell. Does Tableau Photography Deserve to Survive? ArtReview (Available here: https://artreview.com/does-tableau-photography-deserve-to-survive-jeff-wall-white-cube-opinion-dorrell-merritt/)

[ii] This expression was used by Jeff Wall in a talk at MAAT before the opening of the exhibition. The use of this unjustified value judgment comes from the artist using his criteria. It's a statement I tend to agree with, though

[iii] Present in the collection of texts by the artist published by Orfeu Negro

[iv] Welling, James; Fried, Michael. Why Photography Matters As Art As Never Before. Aperture (Available here: https://archive.aperture.org/article/2009/2/2/why-photography-matters-as-art-as-never-before

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

26 Aug 2025

The cause and chance

By Tomás Camillis

Next

article

29 Aug 2025

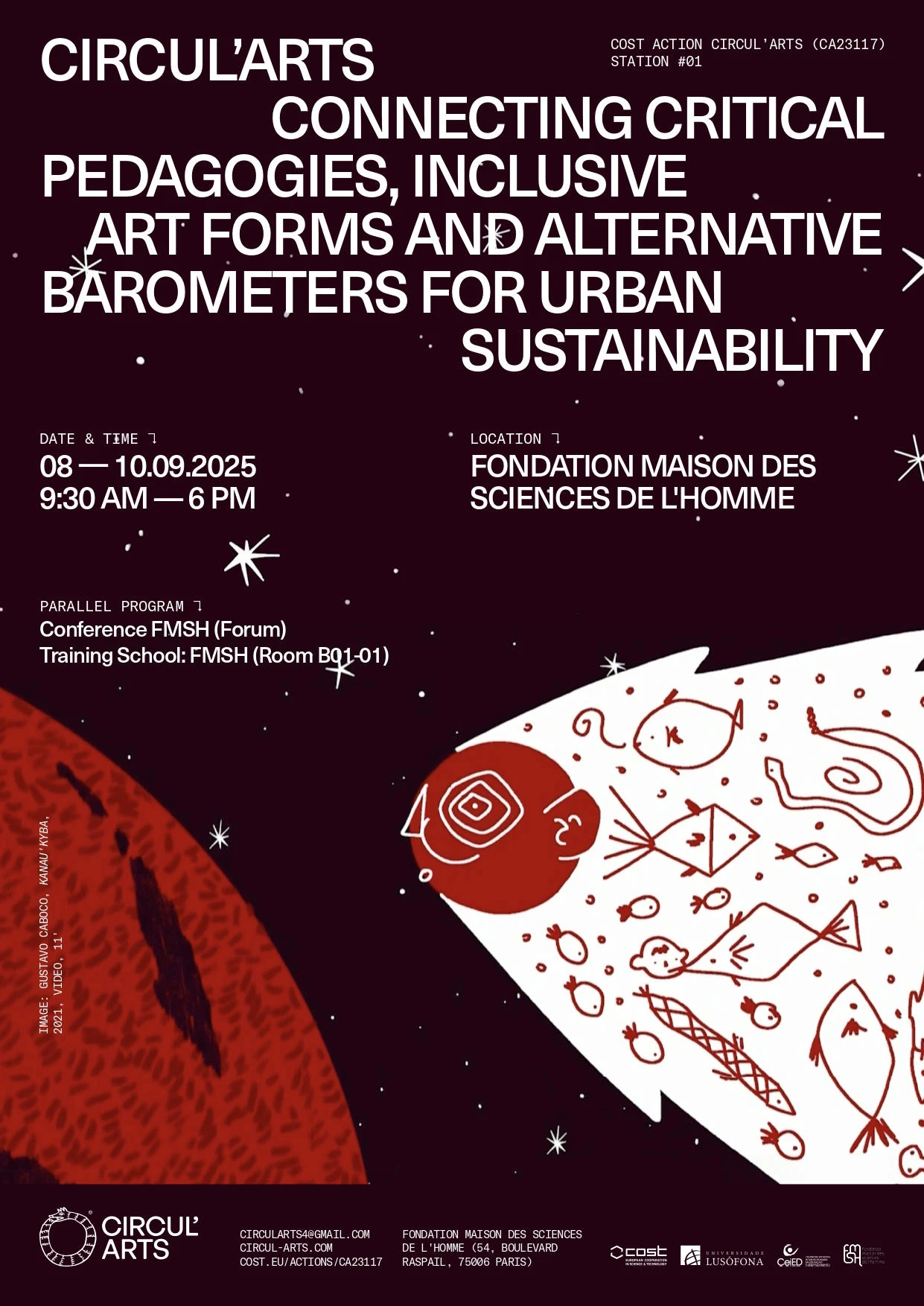

CIRCUL’ARTS: practices, critical and alternative barometers for urban sustainability

By Umbigo

Related Posts