article

Vanishing Act: Eduardo Antonio + Maria Máximo

I step off the bus straight into a puddle and keep walking, head down, hood inflated against the rain. The dark alleyway is one I know well, Resolution Way in Deptford, a slightly out-of-the-way corner of London with a row of young galleries, an unlikely place to find two Lisbon-based artists showing. By the time I reach Studio/Chapple, the rain has turned everything black; it’s only four o’clock, but the night has fully settled.

Inside, my boots drip onto a star-shaped ring painted red and blue on the floor. Off its centre, the strangest object: a delicate wooden tripod supports two gold circular mirrors facing each other, and between them a mirrored obelisk jutting from the wall like a waist-high horizontal Shard. Maria Máximo’s Hotspot (2025) feels both dated and innovative in the way occult instruments do: steampunk, astrological, analogue.

In Máximo’s practice, the body´s language plays a central role. Engagement with her works often prompts an instinctive response – a lean, a bend, a brief surrender. This draws her practice towards performance: the Body as material and subject, often in dialogue with small mechanisms, testing how far we can fold our presence into what she calls the Machine.

She is fascinated by mirrors, especially the concave one for its capacity to magnify and invert; influenced indirectly by Jung’s reading of mirrors as symbols of the unconscious: “Projections turn the world into the replica of one’s own unknown face.”[1] When I lean over the mirrors and align my eye with the reflection, my inverted iris flickers back at me. I feel briefly upside down.

I look up to ground myself. A large painting, 2.5m of oil on jute, draws me into a childhood memory of the circus – sitting in the front row, excited and afraid, watching beams of light spin to the cadence of the music. Eduardo Antonio’s Philosopher’s Stone (2025) conjures that image, an emerald lion and a fuchsia lioness prancing in an arena, their silhouettes haloed by spotlights or the moon, as foliage emerges from the dark background.

Louis, the gallerist, tells me the philosopher’s stone is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals into gold or silver; also known as “red lion” and “white lion” respectively. In alchemical tradition, the stone is symbolised by the union of lion and lioness, masculine and feminine, fixed and volatile. For Jung, this pairing stands for the totality of the Self: the conscious and the unconscious.

Antonio drew from alchemical illustrations in which duality is represented by sun and moon. The painting feels ancient, hieroglyphic, its figures flattened and archetypal. I glance again at the mirrored obelisk, now seeing it as a horizontal pyramid. Later I learn that the first obelisks emerged in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis – the “city of the sun” – where they were seen as petrified rays of light.[2] In the exhibition, the moon doubles as spotlight; the ring’s star echoes the sun. Dualities fold into one another.

The show’s alchemical logic reflects the artists’ collaboration – Antonio and Máximo working for a year to bring Vanishing Act together, partners in work and life, unfolding their relationship into the art where the work acts as a spiritual, generative transformation.

On another wall, a face is glitching: eyes multiplying, canines lengthening, chest sprouting fur. Monga (2025) by Eduardo Antonio, depicts a Brazilian fairground illusion using mirrors and a shift of light to make a woman seem to transform into a gorilla – a simple analogue trick of mechanics and timing. Like Loïe Fuller’s Serpentine Dance (1895–1908), where colour and movement created proto-cinematic magic, it belongs to a time before digital effects, when tricks were handmade. I realise I’ve been circling an aesthetic of artifice. Yet my thoughts go to Muybridge’s flying horse (1878), proof that an illusion can briefly be real.

The exhibition invites a suspension of disbelief, inviting the spectator to believe in the reality of what they observe. Optical illusion becomes the medium through which the union between Body and Machine can manifest – not as trick but as event.

I think of what Federico Campagna calls the “ineffable”, the core of Magic: a mode of reality concerned with what escapes language and measurement.[3] His writing sits in the background of my thinking as a way of naming that slip between what we see and what we think we see – the sense that another reality might run alongside this one. A reminder that not everything must be airtight to feel true.

The day before, at Kerry James Marshall’s exhibition at the Royal Academy, I stood before the diptych Invisible Man (1986): one canvas entirely white, the other entirely black except for a figure almost swallowed by its background. I read the work, as many have, as a comment on institutionalised racism; at its centre is the artist’s own invisibility as a Black man and as an artist. Now, in Vanishing Act, I see him again in Antonio’s The Shadow (2025), a small painting mostly black, a skeleton dancing on a stage framed by red curtains, puppeted by an almost invisible figure. I felt struck by how fully a body can be present and still unseen. Now a gimmick – the “Mr Cellophane” act, or its original version Nobody (1905) by Black vaudevillian performer Bert Williams – using invisibility for gain.

I think of the role of the artist slipping in and out of structures of power, coopting erasure into spectacle; of the circus performer, never quite belonging, the marginalised, the queer, the deformed, the dangerous animal, arriving to town only to bring a thrill to the “normal” people.

The show leans on that feeling – not nostalgia, exactly, but the charm of old illusions. In Vanishing Act, the circus, the holograms, the illusion, the alchemical lion – all become invitations into another reality-system, the one Campagna calls Magic: a world where the inexplicable is not a flaw, but a fundamental principle.

On a stormy night years ago, dressed head-to-toe in black and hidden under a dark umbrella, I crossed a road believing a slowing car had seen me. It hadn’t – it accelerated, and my body rolled over the roof. Alchemists believed the philosopher’s stone could make an elixir of life, enabling rejuvenation and immortality. Cheating death: the ultimate trick. First I was there; then I wasn’t. My own vanishing act. The driver insisted later, shaking: “I looked, but I didn’t see you… you were all in black.”

The exhibition is on view until December 13 at Studio/Chapple, London.

[1] C. G. Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Collected Works Vol. 9, Part 1 (Princeton University Press, 1980), p. 20.

[2] Richard H. Wilkinson, The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt (Thames & Hudson, 2000), pp. 90–93.

[3] Federico Campagna, Magic and Technic: A Post-Nihilist Theory of World Building (Bloomsbury, 2018)

BIOGRAPHY

Mariana Lemos (b. 1991, Lisbon) is a London-based independent curator whose work explores performance, queer/feminist phenomenologies, and questions of illness and disability.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

09 Dec 2025

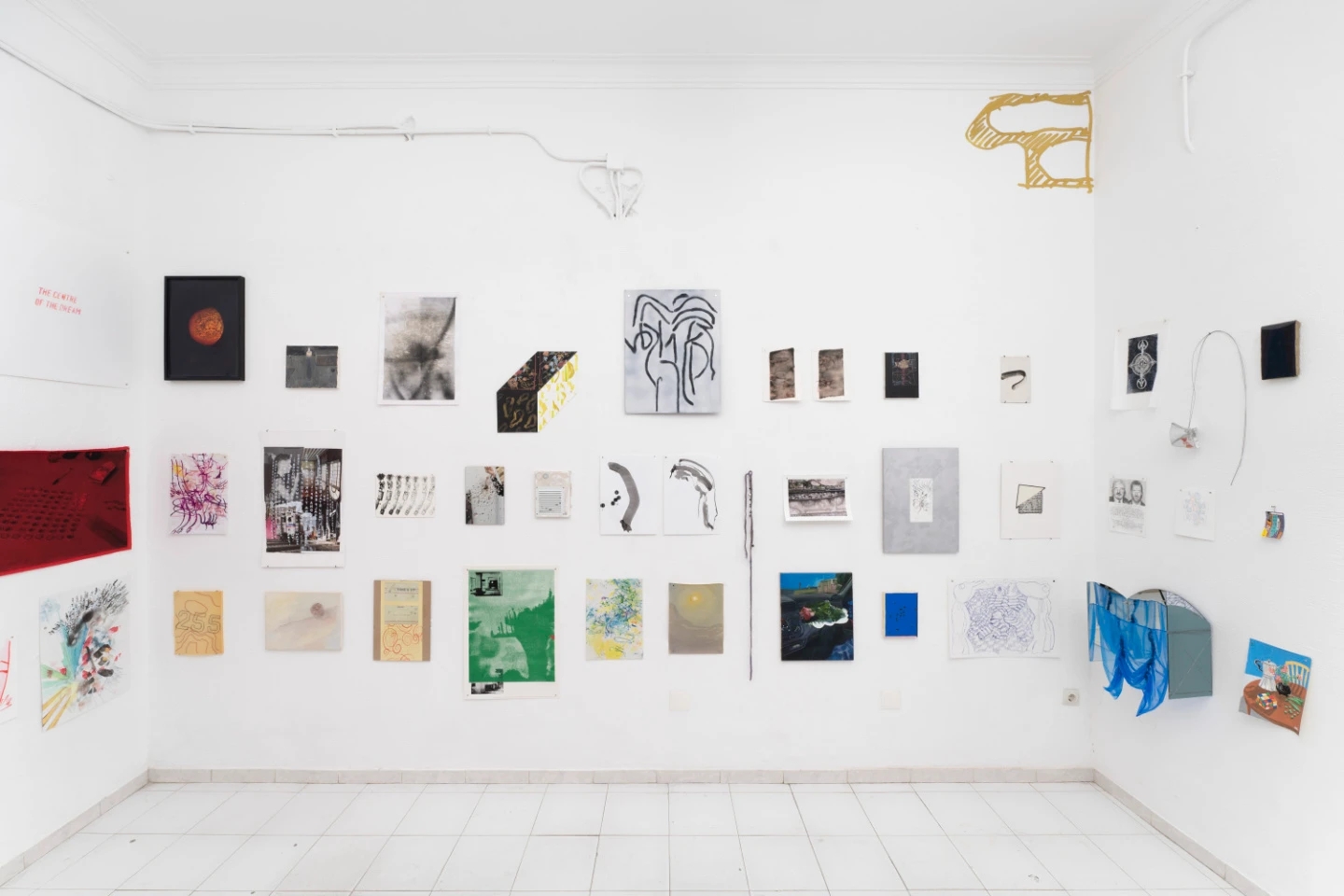

Think of Others: With <3 to Palestine at MALA

By Ayşenur Tanrıverdi

Next

article

-poow5.jpg)

10 Dec 2025

Nage Libre: Sillon Contemporary Art Biennial

By Joerg Bader

Related Posts