30 Sep 2025

Looking Elsewhere: the 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Essayby Orsola Vannocci Bonsi

Titled "Séance: Technology of the Spirit", the exhibition welcomes visitors on a journey through art, technology, and spirituality, a path that is at once historical, cosmological, and visceral. Seoul, with its mosaic of belief systems and religions coexisting alongside the most advanced technologies, becomes the perfect setting for such an exploration.

In 1978, Italy recorded a peak number of UFO sightings: according to some sources, almost a thousand across the country. I first discovered this “alien miracle” a few years ago while reading UFO 78, a historical novel by the writers’ collective Wu Ming, which suggests that in one of the most turbulent years of Italian history, marked by political and social tensions, people, caught between fear and hope, chose to look to the sky, searching elsewhere for meaning.

It is from a similar idea that the 13th edition of the Seoul Mediacity Biennale finds shape, under the artistic direction of Anton Vidokle, Hallie Ayres, and Lukas Brasiskis. Titled Séance: Technology of the Spirit, the exhibition welcomes visitors on a journey through art, technology, and spirituality, a path that is at once historical, cosmological, and visceral. Seoul, with its mosaic of belief systems and religions coexisting alongside the most advanced technologies, becomes the perfect setting for such an exploration.

The curators lead us along a trajectory that shows how, historically, in various periods of uncertainty, including our own, artists, like modern shamans, have turned to spirituality and cosmological practices to respond to crises. They employ less canonical sciences to expand and deepen understanding, entering realities imperceptible to official knowledge. The biennale thus unfolds as a sequence of portals, dreams, and divinations: an artistic sabbath where technology itself seems imbued with a spiritual dimension.

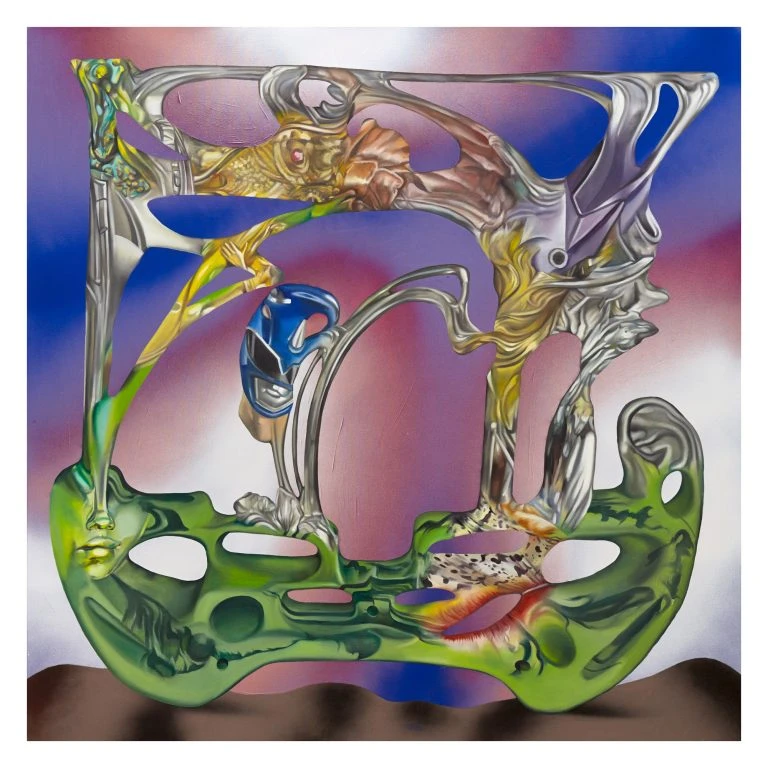

Color is another key element, forming the foundation of the exhibition design. Rather than dividing the space into rigid compartments, colors flow into one another like gradients, recalling their therapeutic properties, their ability to soothe and to stimulate thought. The result is a chromatic cocoon, a sort of mystical spaceship that guides visitors through successive stages of a cosmological yet intimate exploration.

At its main venue, the Seoul Museum of Art, the biennale spans both historical and contemporary moments. It begins with works from the past, as if history itself might be a bridge to the future: the spirit drawings of Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884), conceived as instruments to communicate with entities; the ceramics of Onisaburo Deguchi (1871 - 1948), created while imprisoned by the Japanese imperial regime, molding clay while chanting mantras as though counting beads of a rosary; and the works of Corita Kent (1918-1986), who wove together pop art and religion to capture the tensions of the 1960s. Here, too, is Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), paradigm of the artistic shaman, with his iconic I Like America and America Likes Me.

There are also political echoes of Korea’s own past: Nam June Paik (1932-2006) reflects on shamanism, a practice once suppressed but now reemerging, while Jane Jin Kaisen (1980)’s films draw spiritual traditions from Jeju Island to confront viewers with traumas and wounds left by historical devastation. In this light, mystical and occult practices can be understood as technologies - alternative ones, standing in opposition to extractive, capitalist, and financial systems—capable of easing the alienation those systems produce.

Yet the biennale is not only about spirits, shamans, and memory; it also embraces contemporary and speculative visions. Johanna Hedva (1984), artist, healer, writer, and activist, presents an “alien” kinetic sculpture merging visual art and divination. Yin-Ju Chen (1977)’s installation asks us to see Earth through the eyes of an extraterrestrial colony, questioning the conditions of our survival. And Cyberwitches Manifesto by Lucile Olympe Haute (1984) connects spirituality, politics, technology, and gender issues to imagine more ethical, sustainable ways of being in the world.

The 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale thus poses itself as a journey in which technology is not an adversary but a companion to spirituality, where art and cosmology meet and intertwine to propose new paradigms of knowledge and collective healing. Just as Italians in 1978 chose to look to the skies, this exhibition invites us once again to look elsewhere: not to escape reality, but to find, beyond it, the tools to imagine what is to be.

BIOGRAPHY

Orsola Vannocci Bonsi is a cultural producer and advisor who has called Lisbon home for eight years. Through her work, she fosters connections through her research and the projects she helps bring to life. With experience as a sales director and gallery manager in various Portuguese art galleries, she was also project manager and artistic director of FEA Lisboa, founded the curatorial collective Da Luz Collective, and contributed to the programming of festivals in Italy and Portugal.

Previous

interview

09 Sep 2025

From Screen to Surface: Reimagining Ornament in the Post-Digital Age - Interview with Kamil Bouzoubaa-Grivel

By Alexander Burenkov

Next

interview

01 Oct 2025

Mental Photoshop: Botond Keresztezi on Memory, Technology, and Time Collapse

By Alexander Burenkov

PROJECT SPONSORED BY