article

3 Projetos X 3 Encontros: Networks and Relationships

Artist residencies are becoming increasingly popular, and the structures that enable them, as this popularity grows, tend to multiply and aggregate into national and international networks. The formalization of these artist residency networks allows for the knowledge and access to similar projects, dispersed across diverse geographical locations. Networking becomes a useful tool for those interested in participating in these programs as artists, promoting audiences and allowing connections between the various structures that come together.

Within these networks, the humanization of relationships is often forgotten, a value that could lead such networks to a humanly collaborative operation. While it is true that resource sharing, artist exchanges, and co-programming occur and are promoted with the aim of cohesion and fostering artistic and cultural practices, these generally happen through protocol and as a response to available financial support. Discussion and learning between structures are partially forgotten amidst the need for articulation as a survival tool.

This need for connection among the human mass was the initial motivation for organizing the 3 Projects X 3 Encounters meetings, which have allowed not only the recognition of the similarity of the difficulties and enthusiasms of these peer structures, but also the identification of their human, technical, and material specificities. In this third meeting, keeping in mind the space between network and relationship, PADA, AiR 351, and pó de vir a ser—facilitating structures for artistic residencies and operating in the area of facilitating artistic research and production—met to evaluate the present and imagine the future of the relationships that can be established between them. They advanced in their understanding of the consequences that their organization could bring and sketched out what could be a shared identity, a humanized micro-network. The current uncertainty of their relationships, coupled with the progressive recognition of their distinct identities, purposes, history, and capabilities, is promising for them to be shaped in such a way that the network—here, humanized—becomes operational, contributing to a broader discussion of the importance of these relationships.

Reflection on the future can occur in two ways. On the one hand, through imagination without constraints that allows for subsequent adaptation to reality. On the other hand, through the identification of the constraints that guide the possibilities of building a realizable future. If the first approach can challenge thought without the usual limitations, allowing space for speculation without the logistical considerations that haunt the daily grind, the second allows one not to overwhelm the present with dreams of the future.

For those who operate daily within the possible, navigating the precarious conditions of their resistance, it is natural that a pragmatic approach occurs and that the future is responded to with what is possible in the present. If it is true that between PADA, AiR 351, and the potential to become, the diversity of approaches and contexts is reflected in operational structural differences, it is also true that this operational structuring leads each of the structures to a different model of relational operability. Perceiving this is to understand part of the richness of the possibilities for collaboration and co-learning between structures. And it is also to understand that the future of the relationships that can be created between them will be consequential for the present relationships they maintain – institutional, practical, and human. This relational and collaborative future is designed as a relationship of relationships.

Reinforcing pragmatism and common sense, in order to allow the future of their relationships to unfold, the three structures reflect on the specificity of their programs and the relationships they foster – leaving the dream of the future to the consequence of present awareness.

In a very simplified way, it can be said that AiR 351 prioritizes the resources made available to artists, assuming the role of service provider, guaranteeing working conditions, reflection, and contact; pó de vir a ser assumes a position linked to direct production, where human relationships are built in the day-to-day operations; and PADA prioritizes a close connection to the industrial context, fostering an environment of collective learning and the continuity of artistic work. The specificity of these models means that AiR 351 has a curatorial orientation, pó de vir a ser approaches technical learning, and PADA articulates artistic practice with a structured program that includes visits and critical mentoring.

Time emerges as a scarce resource for each of these structures, despite the differences in their programs, and is one of the main influencers of the characteristics of the relationships established with the artists. PADA recognizes that the need for a rapid turnover of artists, due to the financial sustainability of the project, limits the depth of relationships and the possibility of developing more complex or lasting projects with each of them. In turn, AiR 351 and pó de vir a ser understand that a prolonged relationship with artists allows for the expansion of artistic works and permits more attentive monitoring. To the extent of their capabilities, these structures have been promoting this, welcoming artists at different stages of their projects and creating ongoing relational dynamics. PADA seeks to overcome these limitations through contact and information sharing with its alumni network, but recognizes that the intensity and duration of these contacts are often insufficient.

Secondly, experience allows these structures to recognize that artists develop relationships and collaborative networks that extend independently of their interventions. These small, self-sufficient networks underscore the facilitating role of residencies as catalysts for encounters and multiplied opportunities. It also becomes evident that the impact of residencies is not measured solely by direct intervention, but by the power of influence in building self-sufficient human networks. Maintaining contact with artists allows the structures to measure the impact of their work, identify opportunities for future collaboration, and consolidate a growing network. The effort in this mapping, which is added to the effort of the small teams, is essential to understanding the repercussions of their work.

The relationship with the public is also an important relational dimension to consider. The format of artistic residencies, especially when referring to decentralized projects, promotes direct contact between artists and local communities, contributing to the understanding of the creative process as part of an ecosystem and of artistic practice as a way of life. The work of mediating and facilitating relationships between artists and a general public presents challenges if we consider it quantitatively. The creation of relationships is a result of the balance between available resources and, often, stems from the damaging equation between personal time and work time, extended to all available time, diluting schedules and days off. The proximity that these structures manage to establish would be impossible if this effort were not realized. It is this position that allows them to act as facilitators, promoters of encounters, and mediators of opportunities. At the same time, they recognize the limits of this function: they do not control the unfolding of the networks nor guarantee immediate results, but they create conditions for meaningful interactions to occur.

The role of these structures, often invisible, ensures that artists have access to contexts of production, learning, and collaboration, which are not exhausted by the duration of the residency, but extend through informal networks and constellations of relationships. The impact of different residency programs on artists' careers is, as stated, differentiated, and, hypothetically, the movement between these differences could mean a multiplied impact, combining different focuses and channeling collective energy, even if this implies a reduction in the speed of network expansion.

Thus, considering the present functioning of these programs, the idea of co-programming emerges as a possibility for articulation between structures. As a whole – considering the human element and the material conditions that enable it – a shared program could sustain these relationships and allow for their deepening, which would equally impact the artists' practices and research, maximizing resources and enabling experiences that, in isolation, would be impossible to achieve. Dialogue will be the central tool from this idea; the structures are not reduced to a bland management task, but to the capacity to promote encounters, stimulate conversations, and establish connections that extend the artistic experience beyond the residency period. These conversations, even if informal, allow the structures to begin building constellations of artists whose practices intersect or complement each other, and provide other encounters that promise to be significant. What can be concluded from the present is that the already existing complex relational space must sensibly articulate reality and availability so that the future can be envisioned.

When considering the future of their relationships, sustainability, discussed in the first meeting, takes center stage. New questions arise – all geared towards the balance between resources, time, teams, the gratification of creating meaningful and lasting relationships, and the desire to provide artists with significant and impactful experiences. The triad of residencies, far from being confined to the abstract concept of a network, will build the future within its possibilities, translating its will into concrete actions, encounters, collaborations, and opportunities that, even with scarce resources, sustain the vitality of artistic creation.

BIOGRAPHY

Catarina Real (1992, Barcelos, Portugal) works at the intersection of artistic practice and theoretical research in the expanded fields of painting, writing and choreography, mostly in long-term collaborative projects that address the question of how we can live better collectively.

She is a doctoral student at the Centre for Humanistic Studies at the University of Minho with research that crosses art, love and capital. She maintains a practice of commenting - in the form of reflective texts, introductory texts to exhibitions, interviews and moderating conversations - on the works and processes carried out by artists in her generational group, with the intention of contributing to a healthy environment of criticism and collective and community creation. She has been vice-president of the French association Artistes en Résidence since 2019 and editor at Edições da Ruína since 2022.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

18 Nov 2025

O Museu das Microagressões, de Pedro Gomes

By Laurinda Branquinho

Next

article

19 Nov 2025

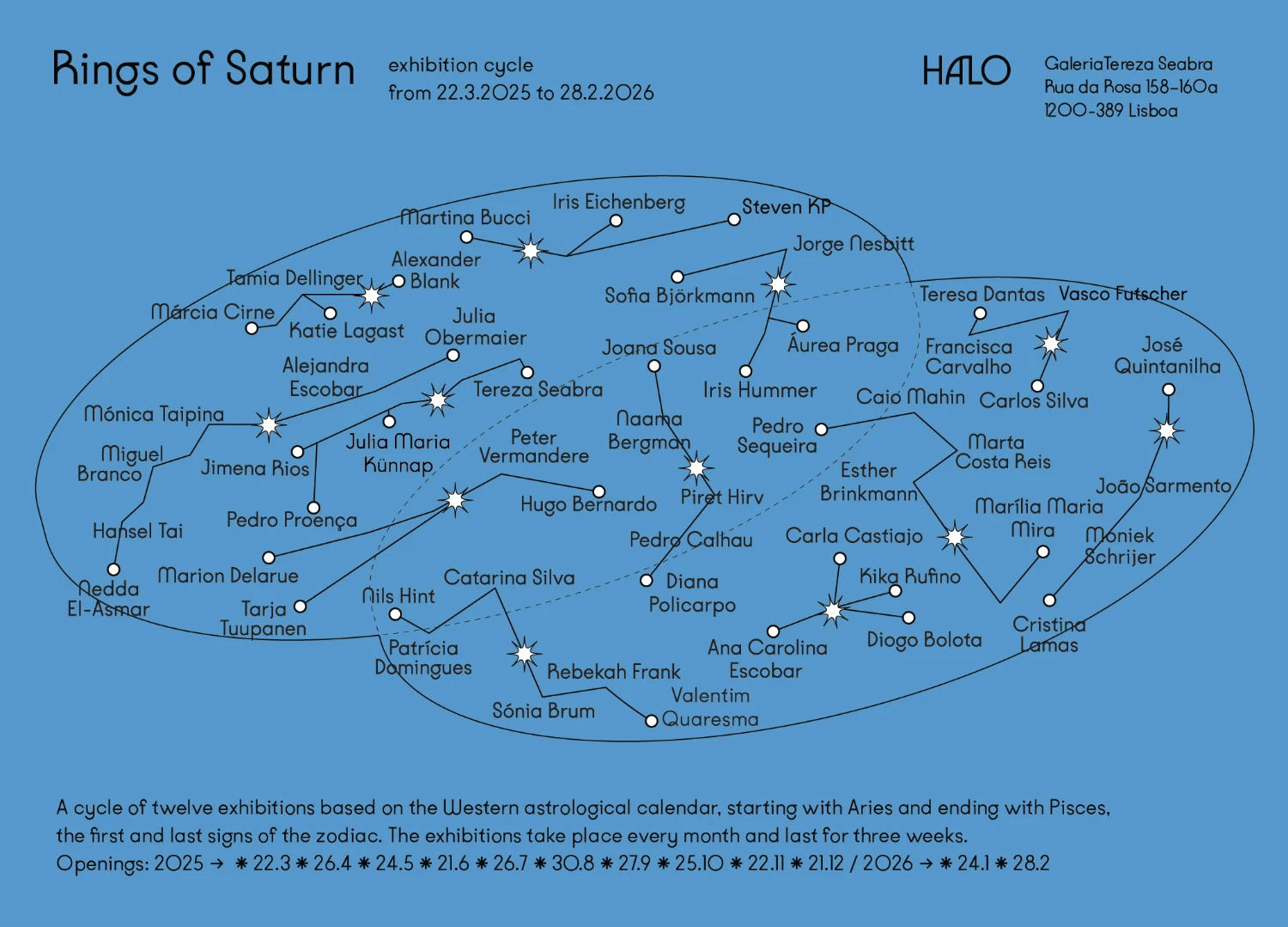

Under the planetary influences: Halo – Rings of Saturn at Tereza Seabra gallery

By Kaia Ansip

Related Posts