article

Crescent Art: Lunário Perpétuo, at Alfaia

Brought together under the curation of João Francisco Reis, the works of the four artists presented in "Lunário Perpétuo" result in an idea of dominated time and liberated temporality, of invoking the past to question the present mode of existence. The times and places that begin as unique, irreplaceable (the sound recorded at that point in the Barlavento, the photographed rock located at a specific point in southern Portugal, the Syrian sand), become, through a "dialogue between science, intuition, and imagination" – in the curator's terms (and, in other words, through art) – transversally and universally human.

First declaration of interests: I have an irrational passion (I believe they all are) for calendars and other lunar timekeeping artifacts. Second declaration of interests: any exhibition with objects that beg me to handle is dear to my heart. Thus, Lunário Perpétuo has appealed to me since I entered the gallery. The Alfaia space has been transformed, once again, to house a delightful collection of visual pieces and a sound installation. I begin by referring to the latter, as the exhibition's Stimmung is conveyed through noises captured in the Western and Eastern Algarve and transmitted, in unexpected harmony, by two speakers in a gallery in central Algarve—Loulé, precisely, belongs to neither one nor the other part of the region. This is the work Barlavento/Sotavento by Inês Mendes Leal (1997), a subtle update of what the artist developed in the 2nd edition of the Visual Arts Course of the Luso-American Foundation for Development in Loulé in late 2023. Facing each other at the back of the gallery, immediately visible to those who enter, the two speakers are like two people facing each other, each pronouncing the voice dictated by their innermost being (they are, in fact, cleverly placed at the height of an adult's head): two people who become one sound; who are only wind, who are only the earth that that sound grounds.

By the same artist, the piece that most directly embodies its title theme was added to this group exhibition, curated by João Francisco Reis: a wooden "Lunário," (Lunar calendar) constructed in five parts representing any of the phases of the moon. It is this object that the visitor can touch, rotating each lunar circle within its respective frame and drawing the different faces of our closest natural satellite. Lunar cycles dominate us, but art allows us the illusion of subverting this relationship of dominance, of acting as if we determine the rhythm of its movement. The curator asks, in the presentation sheet: isn't "the prognosis of a lunar calendar" identical to the divination implicit in artistic creation?

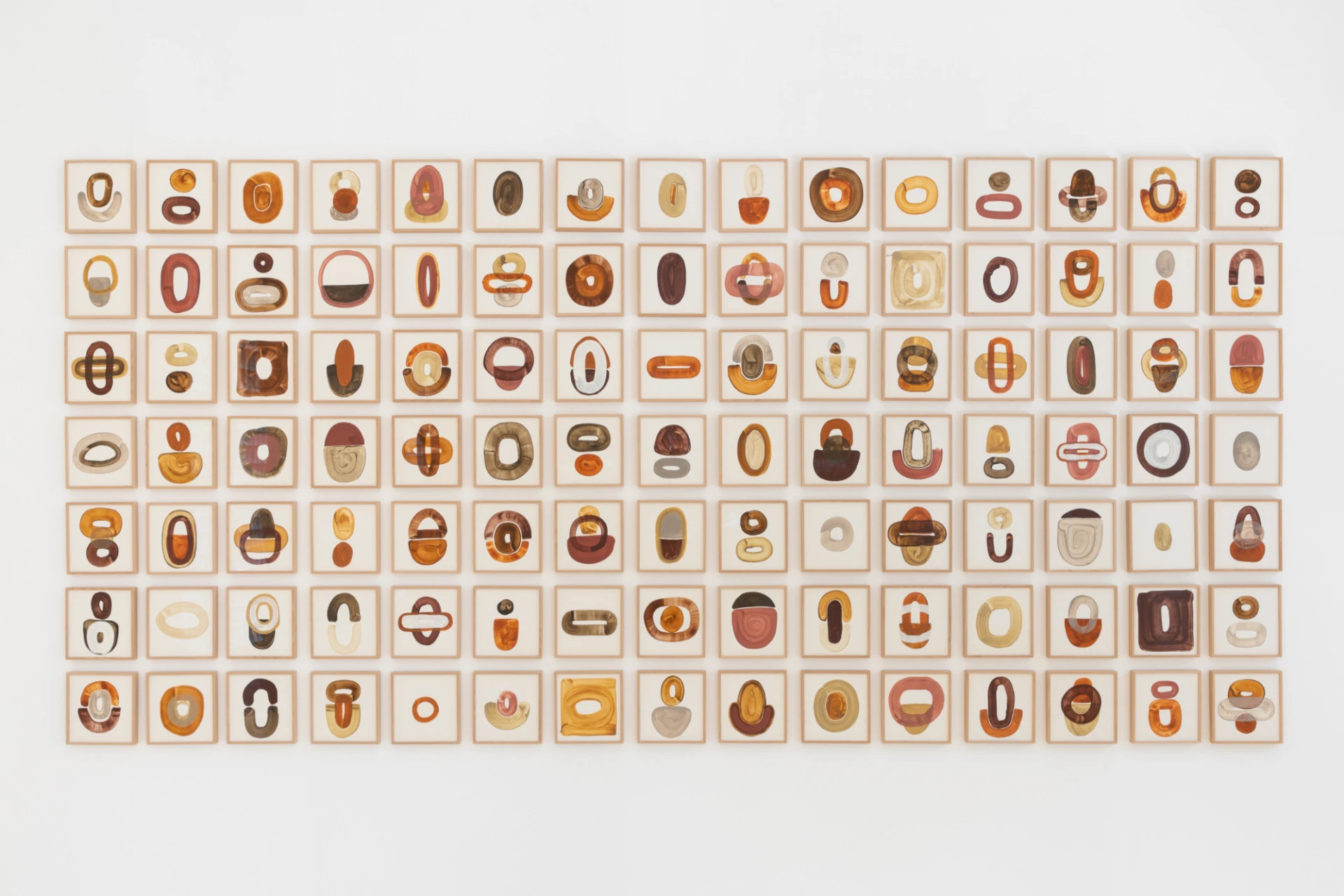

Unlike the lunar calendars integrated into almanacs1 (the oldest date back to cave art, almost as old as humanity itself), which recorded forecasts of the weather and other natural events, such as changes in the moon, this Lunário Perpétuo does not fix anything: it rather destabilizes fixedness and constitutes a challenge to reflect “on the natural forces, cosmic cycles and enigmas that have always fascinated humanity” (text by the curator, cited above). The seven beautiful Indian ink images by Maria Capelo (1970, FLAD Drawing Prize 2022) are an example of this instability. Framed and distributed throughout the gallery, they appear inscribed on the surface of the paper as if they were engravings illustrating pages from lunar calendars from centuries past: these recent pieces are all from 2024-2025 and seem to mimic old oriental engravings, while simultaneously proposing themselves as a visual counterpart to air displacements (in which, incidentally, they compose a dialogue with the sounds emitted by Inês Mendes Leal's speakers).

One could say that the proposal for the Lunário Perpétuo exhibition is based on opposing principles, generated by the coexistence of the irreconcilable (even in this, Barlavento/Sotavento sets the tone: art originating in the specificity of a local territory, by diluting the differences of that territory in the indistinctness or uncharacteristic transmission of the sound of the wind, transforms itself into universal art). It is also based on an understanding of art as a place of play, or deception: consider the photographs of João Mariano (1969), who knows the landscape around Aljezur (Western region) intimately and has been photographing it for decades. In Lunário Perpétuo, they are abstract images, more than signs identifying the places they record. Although this photographer's work is eminently documentary, here that function is removed and replaced by a creative, aesthetic, and not merely replicative approach. Two of the photographs, strategically placed to "embrace" the sound installation, blend in with cutouts on the gallery wall, almost inviting visitors to step onto another side of the space and explore a hidden dimension. The photograph of the entrance, in turn, facing the wooden "Lunário," even without proposing abstraction, reveals a form (of stone? wood? animal?) and is completely at odds with the lunar geometry it confronts.

Robustness and lightness, two seemingly incompatible traits, are equally evident in the sculptures of Maria Trabulo (1989, finalist for the EDP Foundation New Artists Award in 2022). The density of Pedestal IV may contrast with the airy contours of a grid (Window Grid), but all the pieces share in their material the sand from Syria—of which the artist provided some for replenishment. João Francisco Reis selected five samples from the Fragile Stones collection, which the artist created for the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology in Lisbon in 2022, to compose a statement that is both aesthetic and ethical, using primary materials (clay, iron, and sand) and structures based on digital communication.2

Brought together under the design of João Francisco Reis, the works of the four artists presented in Lunário Perpétuo result in an idea of dominated time and liberated temporality, of invoking the past to question the present mode of existence. The times and places that begin as unique, irreplaceable (the sound recorded at that point in the Barlavento, the photographed rock located at a specific point in southern Portugal, the Syrian sand), become, through a "dialogue between science, intuition, and imagination" – in the curator's terms (and, in other words, through art) – transversally and universally human.

1 Publications on which, for example, an Algarve scholar of popular literature, Manuel Viegas Guerreiro, focused, together with João David Pinto Correia, in ‘Almanaques ou a Sabedoria e as Tarefas do Tempo’ ('Almanaques ou a Sabedoria e as Tarefas do Tempo’), an article published in volume 6 of the ICALP Magazine (August/December 1986).

2 They resulted from the dynamics of preservation and memory of archaeological artifacts that were part of the Raqqa museum and the Syrian Heritage Archive, almost completely destroyed by the invasion by the Islamic State, and whose forms a group of Syrian archaeologists and historians exiled in Germany are recreating.

BIOGRAPHY

Ana Isabel Soares (b. 1970) has a PhD in Literary Theory (Lisbon, 2003), and has been teaching in the Algarve University (Faro, Portugal) since 1996. She was one of the founders of AIM – Portuguese Association of Moving Image Researchers. Her interests are in literature, visual arts, and cinema. She writes, translates, and publishes in Portuguese and international publications. She is a full member of CIAC – Research Centre for Arts and Communication.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

18 Aug 2025

Que Emoção!, at Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes

By Carla Carbone

Next

interview

20 Aug 2025

Interview with Marta Castelo, author of Umbigo´s monthly cover

By Maria Inês Mendes

Related Posts