Cinzento/Grey/Gris by Ignasi Aballí, at Galeria Vera Cortês, in Lisbon, encourages us to draw a spatial geometry that (re)shapes us as compositional elements of a plural space, more than just inviting us to an aesthetic experience of sheer contemplation. If we see coloured windows, we become coloured windows. If we watch typographic stamps with the word grey spelled out in multiple languages, we become memos reproducing themselves across unexpected geographies. If we see newspaper clippings jumbled up with poetic-dictionary definitions of colours, we are already the announcement of a new light beam. In all fairness, there is a coincidence to be said between the contemplative nature that every work of art entails – the tempted glance – and the architectural component, from which the exhibition’s audience becomes an active component in the way that place is experienced and/or inhabited and inhabitable. As a matter of fact, to say how something is instantly means to say how it is not yet and could become. For example, Aballí uses chromatic schemes to provide us with the terms and conditions for inhabiting the world – consisting of all those colours and some others that will exactly be a light gap, a distraction from all the atoms other than those included in the shaping of the new colour, and the rush of desire for the beholder.

The Babylon embodied in the exhibition’s title is not so much a sign of difference as it is of an echo, at the precise moment when one sound meets another, similar one, the result of which is an overture to what is different, what has never been heard or seen before. Most impressively, this difference never goes to the often addicted and autistic place of the so-called exotic, which, rather than shifting attention to what is alien, indulges in the validation of a supposed identity and a privileged place, resulting in patronising gestures. We suddenly realise – and we astonish ourselves in this shock – that this difference, and soon this call for an intersection, for an experiment, had been there all along. In potency, whose idea is not confined here to a positive value, an alternative expanse of the world as we know it. Potency means coming across our own image, scrutinising other forms, other faces, and sometimes not being able to break out of that reflective bubble: just like that series of paintings with a caption which is gradually rubbed out by the darkening of the next canvas, until we find ourselves, our mirror image. And there Aballí can hardly be clearer: he wants us to be capable of being seen, of seeing ourselves as a witnessed form, a sign of distance and perhaps a broken lighthouse or compass; a broken one that nonetheless allows others to include us in their private mapping, to seek us out and vice versa. Meanwhile, the artist offers a sort of commutative property of vision: if one disappears, the other emerges. One’s shadow gives the other its halo. Also, the obliteration of forms leading to the clarity of our mirror image sums up the power of the glance as a democratic transmission operator, since through our reflection we are forced to identify ourselves as a foreign body, an alien sign, an uncertain movement. Our sight gives us our life as a vanishing ballast, of which we are no greater owners than the others we pass in the street every day and whose names we never get to know. Calling each shade of blue or brown or grey a code is a compliment and elegy for what we do not know, for the messages we have lost and for the walls we have built that cannot even withstand a roof. This is a way of exposing, strictly speaking: as archaeology and a magic trick, the archive as the deed of a lovesick madman who keeps a record of his fantasies based on the smallest details of reality. Ultimately, the scientist who builds his novel and calls us all into his alchemical laboratory.

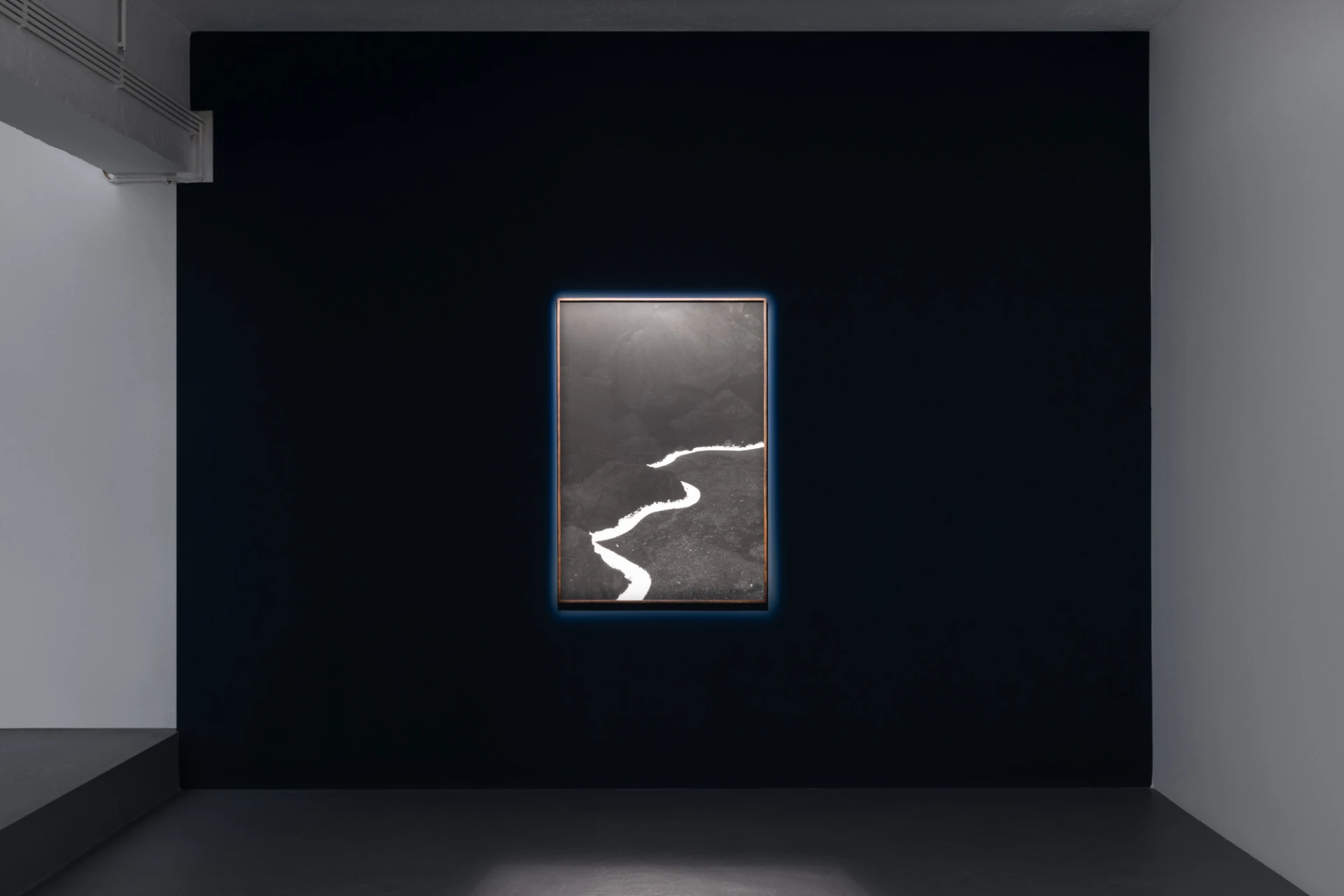

In the beautiful exhibition text by Maria Azparren, the author alerts us to the fact that a type of grey, Eigengrau (‘intrinsic grey’ in German), is the first colour we see when we are born. This same colour is brought back each time we close our eyes and open them again. The eye then undergoes multiple rebirths every day, bearing in mind that the average human being blinks 28.000 times every 24 hours. The exhibition is at times sober and almost frostily architectural, and other times produces sensations close to hallucination – for some moments I felt my vision blur as I searched for the similarity between one tone and another, without ever being certain about the relationship. Desire and mystery led to the formation of a fictionalised image, with the frankness to be built up as a cloudy panel, permeable to other forms, other films and other senses. To be in Ignasi Aballí’s exhibition is like stepping back into the moment when our eyes first opened and we were pushed to arrange the world that already existed and, at the same time, to tackle the emptiness around what we call home: to look at language as a dream too tangible to be random, not tangible enough to be a caption. Above all, art as the return of the poetic.

Cinzento/Grey/Gris is at Galeria Vera Cortês until March 8.

-rwdro.jpg)