article

The new Julião Sarmento Pavilion

The Julião Sarmento Pavilion, inaugurated on the 4th of June, makes an impression even before entering the space that houses the inaugural exhibition, with around eighty works from the 1,500 in the artist's private collection.

The building in Belém, formerly the Blue Pavilion, renovated according to a project by architect João Luís Carrilho da Graça, is painted entirely white and faces the river, with some windows covered, reproducing the same colour as the building. A block of brightness, a mirror of light that reflects, illuminates and/or dazzles. The entrance is on the side of the building. This is perhaps the most interesting angle, in fact, to metaphorically think about the condition of the artist-collector: the one who becomes, more than a canvas, a picture, a screen, the projector of stories that are equally constitutive of their work. The constitutive generosity of the creator. The immeasurable trail of his craft. The mystery of its appearance and its trail.

Under the direction of Isabel Carlos, the space aims to establish a dialogue between artists from diverse backgrounds, in line with Sarmento's multifaceted work. The first exhibition, Take 1, curated by the director and borrowing cinematographic vocabulary for its title, brings together works by various artists, both Portuguese and foreign, and is spread across three floors. On the ground floor, painting, photography, sculpture and a large intervening space present a museological configuration that makes artistic objects elements of a path to be followed, participants in the inhabitation of a place and the sensitive experience of space. In the very first gallery, Robert Morris's work, Untitled '76/Felt (1976), combines symmetry and darkness, graphic design and body, line and texture: the piece could be presented as the blueprint or draft of any element to be built, yet to be born. On the other hand, the black of the felt devours any logic that is not purely contrastive, made up of tensions with the space in which it is displayed, seeming to be defined more by what touches it, from the outside, than by what it contains. The coloured elements are, curiously, on the floor, in the form of two rugs, one by David Hockney, the other by Richard Long.

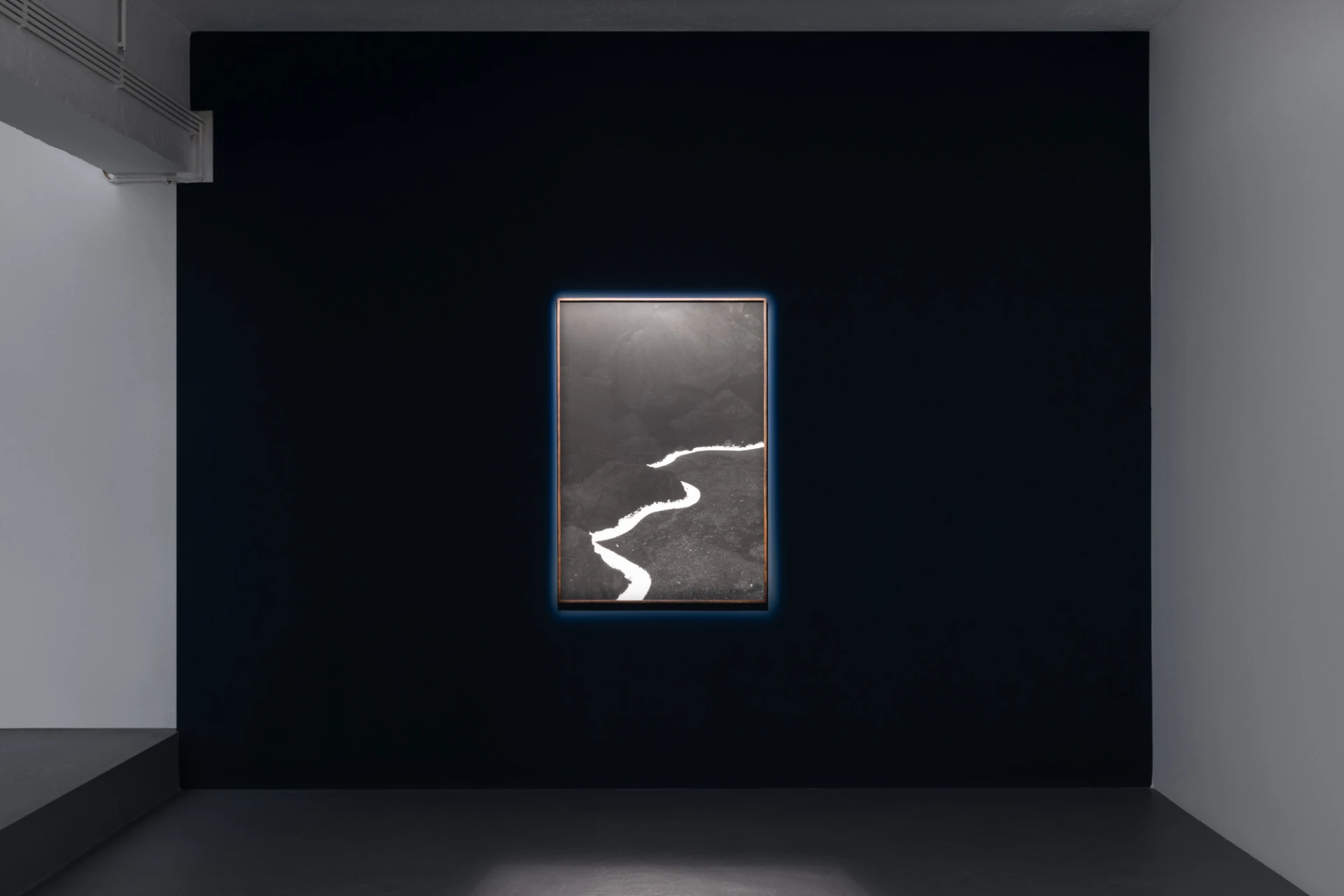

The immersive, laminar coldness of the first gallery—oriented around the theme of architecture—is counterbalanced by the darkroom on the lower floor, which features a film by Marina Abramovic, Dragon Head 6 (1986), photographs of the artist by Paolo Canevari, and Pozo II (2011) by Cristina Iglesias. We return to a mythical time. Here, the awareness of an ancient memory evident in the renewal of the scales of the serpent that encircles Marina’s neck in the video, the passage of time as a singularly experiential substance in the rising and falling of the waters in the well, whose bottom takes the form of a premonition, a quasi-presence. And the waiting: for the expressive change of a face, in Abramovic’s video, and for the new vision of the stone above and below the waters. Ultimately, this is the return to the time of figurations, of the signs of the connection to the powerful unknown matrix.

On the first floor, something like private correspondence is mapped by the presence of portraits of Julião Sarmento made by friends, including pieces by Fernando Calhau, Joseph Kosuth and Miquel Barceló, among others. The diversity of the pieces, their distribution throughout the pavilion — in the bathroom, the soap with a blade applied, by Susana Mendes Silva — makes the artistic objects elements, more than potentially compositional elements of an everyday and familiar territory, components of an enchanted world, from whose testimony it no longer makes sense to distinguish a so-called real life from another created life, given that both planes will intersect in the living mirror of desire. Take 1 places itself outside of any historicist pretensions regarding Julião Sarmento's work, an approach that so often focuses on the works but ultimately forgets to pay attention to them, hostage to an entire critical apparatus, to an entire tradition and genealogy to which it supposedly owes a repeated, citational corroboration.

A bit like the mystery collector in Virginia Woolf’s short story Solid Objects, who is determined to find strange objects—unlocatable accidents as a narrative to be traced, the presence of new matter to be created—this exhibition witnesses the frank admission that everything an artist touches is, from the outset, a message received from somewhere else. The impossibility of absolutely determining the birth of artistic forms makes them permeable to endless combinations, presided over by the desire to join, to touch, to provoke friction, to have as raw material the inescapable, yet astonishing, mystery of the body and its correspondences.

BIOGRAPHY

Master's degree in Portuguese Studies from Universidade Nova de Lisboa, with a thesis on Nuno Bragança. She is currently writing a doctoral thesis on Agustina Bessa-Luís and Manoel de Oliveira and melancholy. FCT scholarship holder, she has contributed to anthologies and has published poetry and essays in national and international magazines. She has published two books of poetry: “E o Coração de Soslaio a Todo o Custo” (2025) and “Penhasco” (2025). She is co-editor of Lote magazine. She writes literary criticism for the Observador newspaper.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

24 Jun 2025

By António Figueiredo Marques

Next

article

27 Jun 2025

The Condominium and other forms

By Filipa Nunes

Related Posts

-rwdro.jpg)