The essay finds the best conditions to survive in the in-between zone between lógos and poíesis, rigour and originality, calculation and deviation, research and invention. It is within this transitional gap that the essay-form’s interdisciplinarity becomes unruly, a joyful rebellion of concepts, forms, systems and orders. The essay explores transient and fragmentary details, rejecting the obligation of an apparent totality for the sake of a constellation of ambiguities and concerns. Unfazed by accusations of eclecticism or absence of truth, the essay challenges us to free ourselves from the invisible shackles of the method: the method of doing and reasoning science, philosophy, literature, film and the visual arts.

This is the theory and the mantra that echoed at Carpintarias de São Lázaro, in Lisbon, on March 3 and 4. Over a weekend, the fifth edition of the Purga project took place, an exhibition called Estudo do Meio, conceived and organised by Isabel Cordovil and Rudi Brito. Featuring 24 artists and lots of beer and relaxation, the proposal was for a free, experimental and collective programme, in the most essentially anti-essentialist meaning. The focus was in the middle: in the field of art, in the centre of creation and in the transition between the beginning and the end.

The event was not limited beforehand, as it happens in a rehearsal, as stated in the official press release of the cultural centre. It was not a “visual artists’ collective, nor a performance festival, nor a series of concerts”. Rather than seeking scientific validation or creating something artistically unprecedented, the value and boldness of an essayistic curatorship lies in reclaiming the ability to be surprised: “[…] its efforts still mirror the willingness of one who, like a child, is not ashamed to be excited by what others have already done”, as Adorno stated, defending the essay form as a singularly reflective expression in which “[h]appiness and play […] are essential” [1].

In this play, of which we do not know or share the rules, subjectivities do not appear immediately, but rather through the effort of bringing to light the specific configurations of the objects on which they dwell. There were two afternoons and two nights dwelling on the restlessness of this desire – the only duty of the essay (I feel the urge to extend the sentence with indents that include “also that of the arts”, but that would be naive). Strolling aimlessly through all the floors of Carpintarias, I often reached the door and turned the exit into an entrance again, zigzagging, circling, sitting, drinking, laughing and completing the itinerary between the works again. And yet only one more time. Another beer? Now I’m off. Oh! Is it already time for the next performance? Estudo do Meio ended without coming to an end, without exhausting its (more or less) confidential search, in this pursuit of will and freedom in an intermittent and fickle rhythm.

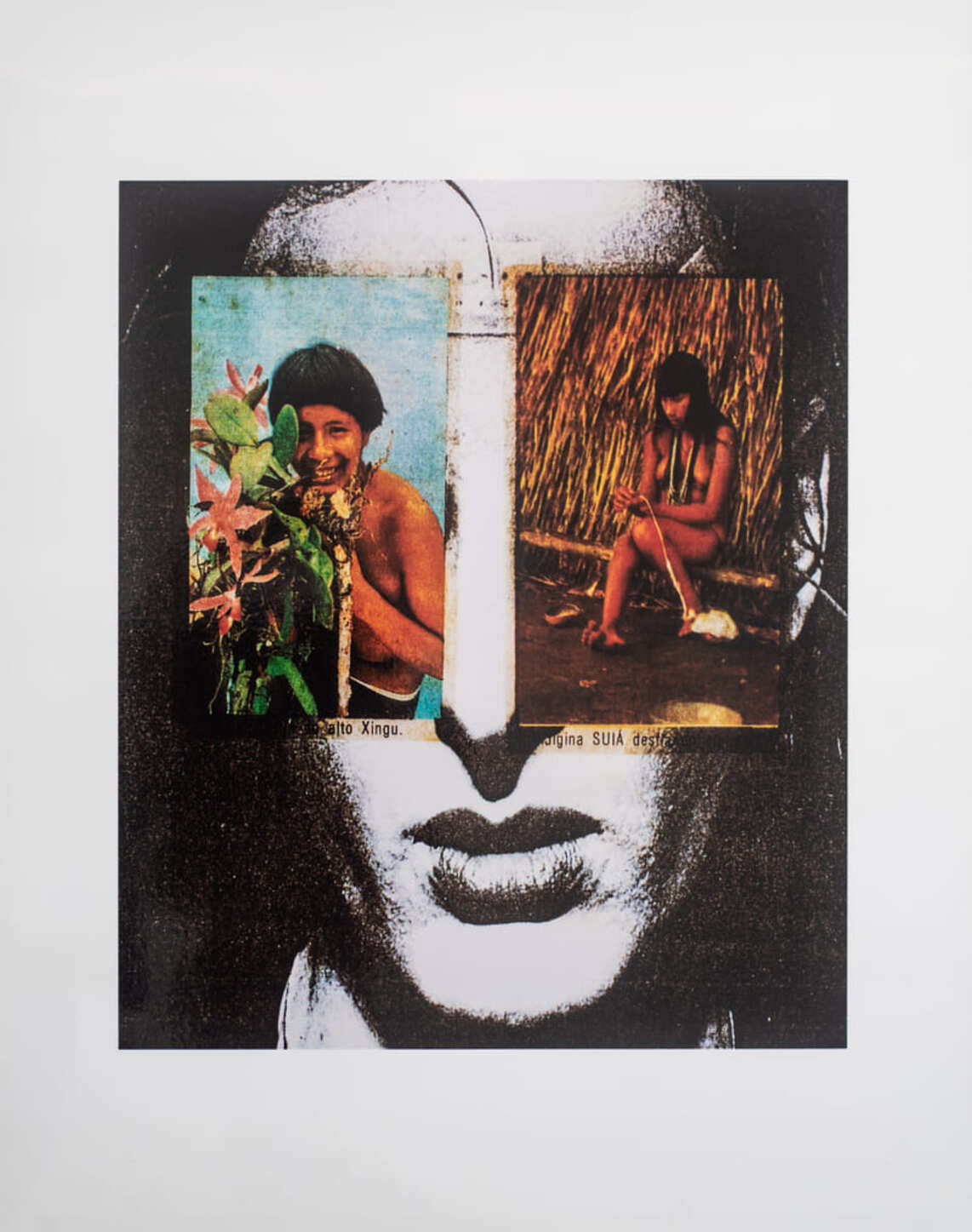

An essayistic practice that appreciates playfulness does not have a defined finish line, but it still provides important and positive discoveries. For once, I highlight the mesmerizing film by João Bragança Gil Anticline(2020), side by side with One Last Longing (2020) by Henrique Pavão, attracting us through the beauty and drama of the images, until it is already too late – we are immersed, drowned in an ecology of wounds and pain. Rudi Brito’s photographs also leave their mark, whose presence and contrast are felt at first sight, inviting us to grope with our eyes the grains, textures and movements of Container (2020). If these visual essays awaken our urge to touch, Diogo Bolota’s Uma escultura dá sempre vontade de comer (2023): from the ears between leaves – indeed tempting -, and the vibrant, sinuous figures in Phantom (2023) by the talented Ema Gaspar, awaken our taste for a miraculous fantasy that infects us and becomes a bit more real. As Lukács had already anticipated, “[…] just like Saul, who went out in search of his father’s donkey and found a kingdom, the essayist capable of seeking the truth will reach, at the end of his path, something he did not seek: life” [2].

I wish this brief article had disregarded my initial expectations and outlines and taken on the broader contours of an essay. I feel it would thus have been a more honest literary attempt at my subjects of analysis: Estudo do Meio and, ultimately, my own desire. However, I rejoice in the acknowledgement that the internal dissent of essayistic force can only result in an inevitable lack of final conclusion. I remain halfway there – indeed, the only place there is to be.

[1] Adorno, Theodor. (2003). “O ensaio como forma” in Notas sobre Literatura I. São Paulo: Editora 34, pp. 16-17.

[2] Lukács, György. (2014). “Sobre a essência e a forma do ensaio: carta a Leo Popper” in Serrote. São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Sales, n. 18, p. 44.