This essay proposes reflections based on 12 exhibitions currently on display in Munich, as well as the experience of returning to the German city at the invitation of Various Others. I write about writing and learning, about wonder, democracy, care, technology and ghosts, among others.

May 8, 2025, Thursday

I’m at the Lisbon airport and I’m sleepy. It’s been a long time (a few decades, even though I haven’t yet reached my third one in life) since I last wrote in a diary, and now I’m not entirely sure why this seemed like a good idea. I’ve never been particularly drawn to the format of an intimate description of everyday life: at the height of my self-assuredness as both a psychoanalysis reader and analysand — combined with a personality rather prone to intellectualizing everything — I’ve always considered the effort of giving concreteness (or, in fact, just a second abstraction) to the words that I had already known inside myself to be dispensable. If it doesn’t even interest me, why should it interest a reader? That was my conviction (I hope to be convinced otherwise). In any case, I admit I’m embracing the diary form for a deeply personal reason: to recover a sense of experimental play in writing, and the pleasure of thinking from the outside. Turning a childhood dream into a profession is, at once, an adventure and a trap: between exhibition texts, critical essays, and academic articles, I sometimes feel like a tightrope walker — joints stiff, stomach tight. I need to remember to move slowly, to loosen the ligaments, to carry language close to my chest, careful not to let it fall and shatter on the ground. But I am safe, I have ropes around my waist — and so I let myself write more freely, even though I know perfectly well that I will have to take a few steps back to change a word here, remove a comma there, look for a synonym somewhere (I have already done so).

I am once again traveling to Munich at the invitation of Various Others (VO), an initiative that, since 2018, has inspired international exchange and cooperation between galleries and artist-run spaces, which come together to co-create new exhibition and social programs. I think about returns and the expectations of finding the same city again a year later. The streets of Munich will surely be just as clean and orderly as I remember them, though this time with a slightly colder breeze: we’re still in spring, unlike the last edition of VO, which took place in the summer. I anticipate the exhibitions I’ll see, browse the press program looking for those words and images that already catch my eye, place an asterisk next to some venues, pencil in activities and visits in between. I think about the gatherings, the coffees, the dinners, and prepare myself for days of many kilometres walked and a considerable amount of social energy spent. I’m not complaining at all — mind you, this is exactly my idea of a weekend well lived.

The trip I have ahead of me is not that long, but, of course, I had to arrive at the airport two and a half hours early, as usual. Not long ago I was still participating in a conversation about what a school for radical imagination is or could be — a question that leads me to another inner concern that deserves to be brought outside: what was the last thing I learned? What types of dispositions and devices can trigger a learning process, a new synapse, a spontaneous sigh? Now seated on the plane, floating with tons of steel in the sky, I realize that this is also the challenge of an immersion in art, in a city that is not my own, with people (still, or not entirely) strangers: letting yourself be surprised, unlearning something, fermenting something else.

May 9, 2025, Friday

I landed in Germany after the official opening of Various Others. I missed a literature class at the university in Lisbon; a series of gallery openings in Munich; and all the countless events around the world that were happening between 5 pm and 11 pm yesterday. My personal event was reading, writing, running to catch one of the last trains, dragging the unsteady wheels of an old carry-on through the city center, and finally lying down in bed just to have insomnia (I thought of that sentence before arriving at the hotel, and I feel like I conjured my sleepless fate). In the morning, I meet three familiar and welcoming faces, press colleagues from Berlin and Glasgow: Urte, Susanne and Toby. Together, we head to the Herrenchiemsee Palace, in Chiemsee, to visit the recently opened exhibition Are we still up to it? – Art & Democracy, curated by Verena Hein and Oliver Kase. On the way, we are offered fresh croissants, carefully tended as always by director Christian Ganzenberg and the entire Various Others team. The German voices around me sound like background music, and, unable to assign meaning to the sounds, I let myself drift into thought while watching the flat landscapes and countryside houses pass by through the window.

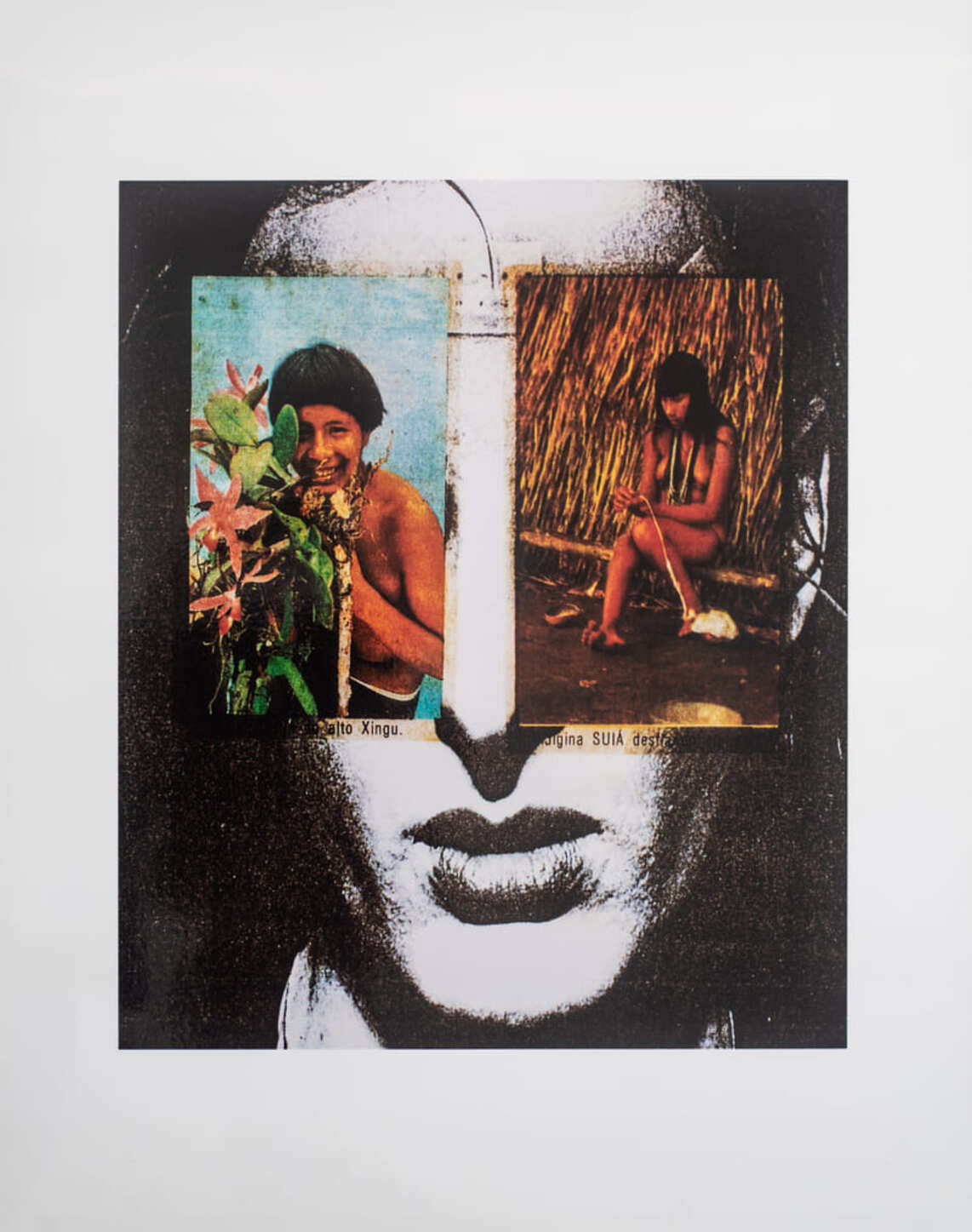

I start thinking about two questions that seem essential to the conversation about democracy. First, the problem of translation (or, more broadly, of transmission): when there is no shared language, a simple hand gesture, a difference in look or a change in posture can indicate the focus, the importance of something. Without knowing the expressive codes of a given community, other ways of situating oneself in space and paying attention are necessary. Then, I ponder what it means to think about democracy from that specific place: a royal palace (modelled after Versailles, a symbol of the absolutist monarchy and home to the longest reign in history, under Louis XIV), located on an island. At first, it does indeed seem like an inadequate undertaking — intuitively, we feel that democracy lives where the people are. But are there (or should there be) restrictions on its extension? Surrounding the Palace, Lake Chiemsee — the largest lake in Bavaria — is home to over 1% of all wintering bird species in the world, as well as of several endangered fish. Wouldn’t public life be there too, on an human-uninhabited island for part of the year, surrounded and entangled with what we call nature? Still, I leave the exhibition convinced that democracy is not green. It is, in fact, always red — the color of revolution, of wounds, of war, of desire, of bricks — as proclaimed, even, in Rose for Direct Democracy (1973) at the start of the show. Are we still up to it? – Art & Democracy is, without a doubt, a gathering of giants: the ever-impressive Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol, as well as Thomas Schütte and Sheila Ricks, highlighted by the curators. Personally, I’d point to two works whose force remains striking at every encounter: Democracy is Funny (1973) by Joseph Beuys and Teaching A Plant The Alphabet (1972) by John Baldessari.

From there, we return to the centre of Munich for what will be the first (and strong) tour between galleries. At Nir Altman, winter resonates — as do war and isolation — in Now the east wind hunts, the fourth solo show by the British duo littlewhitehead in the space. Through their characteristic, somewhat sculptural compositions — in which images are gradually reduced to almost abstract forms, which then gain relief on the canvas —, tinged with cold and pale tones of blue, pink and green, the gallery transforms into a forest of ghosts, perhaps disappeared beneath thick layers of snow and abandonment. At Sperling, which partners with Mexican gallery Pequod Co., Malte Zenses (born in Solingen) exhibits new works produced during a residency in Mexico City — and which also unfold simultaneously in his first solo show in Latin America —, and Andrew Roberts (born in Tijuana, a city bordered by the most-crossed frontier in the world), presenting his first show in Germany. According to the gallery directors, this is the first two-way collaboration fostered by Various Others, in which the German part also travels across the Atlantic. Once again, I reflect on the experience of belonging that can emerge from the difficulty of transmitting codes. This time, however, I also recognise the importance of sometimes resisting the urge to share — of reaffirming the non-communicability and otherness of certain signs, ways of living, or subjectivities. During the guided tour at the Palace, the use of German was insisted upon. Zenses, in Latin America, insists on painting — in a context where, as the directors noted, the politicisation of art often demands that painting constantly justify its own existence. The result is an intimate, lucid exhibition which, in some ways, also resembles a diary.

At Britta Rettberg, together with The Breeder, from Athens, and Ravnikar, from Ljubljana, six artists make up what, among the selection of what was possible to visit in three days, I consider to be one of the most coherent and delicate exhibitions of this edition (later note: on the next day of this journal, others would join this group). In This Must Be the Place, the care is evident not only in the selection of works and authors, but also in the investigations that inform the practices of Nina Celhar, Laura Ni Fhlaibhin, Kyriaky Goni, Caro Jost, Malvina Panagiotidi and Helena Tahir. From the island, we go to Mars, and I allow myself to expand the question about the place of democracy (and of colonialism and imperialism) to other planets. Still, a common concern is the earth — the earth that holds traces of displacements, family memories, plastic, worms, mushrooms and (even!) ordinary words and objects. I particularly learn from the speculative vocation of Laura Ni Fhlaibhin, who weaves stories of illnesses and healing shared between humans and non-humans, reminding us of the beauty and responsibility involved in a process of interspecies mourning and preservation.

Before heading back to the hotel to recharge all my batteries, I manage to add one more exhibition to my itinerary: Works of Wonder, at the ERES projects space. Among objects from the Renaissance and Baroque periods and contemporary pieces, the exhibition brings together extremely sophisticated handmade works — whose preciousness also derives from the initial recognition (and intensification) of the rarity and beauty that already exist in the world, among, for example, the animal and plant bodies with which we live. Incidentally, the title of the exhibition — the last of the day — literally evokes what I had said was the challenge of such an artistic immersion: to release a genuine “wow”.

I wrap up Friday feeling warmly welcomed at one of the dinners hosted by the galleries. I talk about childhood and adult dreams, artist books, autonomy, investigations that last and relationships that end.

May 10, 2025, Saturday

Today, the second round through the participating galleries begins, luckily, later in the morning, which allows me to spend more time at the breakfast table writing. I feel rested and energised for what I already know will be the day with the highest step count on my phone. I am late for the first meeting point (after being at the wrong address with the usual anxious punctuality), but I am greeted with the sweet and understanding smile of Lucrezia Levi, communications coordinator for Various Others, whom I had not had the pleasure of meeting in person until then.

Right at the start of the tour is nouveaux deuxdeux — which I remember from the last VO as having an exciting program with emerging artists. Once again, it does not disappoint: with SYZYGY, the molecular research of Thomas Feuerstein (represented by the Viennese Galerie Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman) and the neo-machines of Mona Schulzek are perfectly aligned. With both, the technological imaginary is re-materialised, given weight, metabolism and an equally wild idea of the future. Here, too — as in the show at Britta Rettberg — the research carried out by Schulzek, in the context of intergalactic communication and deep time, and Feuerstein, with his biophilic activations, translate into works of remarkable and invigorating conceptual depth.

By now, it should be clear to the reader that I have a special affinity for the themes of ecology and more-than-human relationships (whether with living or non-living matter). That is why, although I missed the official reopening on Thursday, I had to include a visit to Lothringer 13 Halle on Saturday — a municipal gallery that, under the new direction of Kalas Liebfried, aims to radically incorporate the community-based and experimental values of the space into the artistic processes it fosters and exhibits. In Anarchic Animism — a programme in conjunction with the annual ECOCIDE Festival and within the scope of Various Others — we meander through dystopian environments that sometimes take us to a humid underground, sometimes to a romantic scene of nature taking back the earth, sometimes to the launch of a rocket (with very exclusive seats) towards the conquest of another planet. In any of these scenarios, the future has already been cancelled (Future Cancelled, 2018, Georgi Gospodinov): we are no longer there, or we cannot get there. In the painting that “mirrors” one of the gallery’s rooms (Scenography, 2025, Paul Valentin), everything is duplicated, except us. Junk sentinels move through the space. Ailing objects rehydrate and play music by themselves — an impressive visual and sound installation by Antoni Rayzhekov (Until the Last Drop, 2022), where the each falling drop of scarce water erupts a musical note. We wait, immersed in the tension between those bodies, for the rare moment when drops fall simultaneously and an orchestra is formed. When the exhibition is dismantled, the void will be ours alone — Maxine Weiss’s parasites (Deepwater Horizon, 2024) will continue to appear, of their own accord, on the walls.

I have some time before the VO’s collaborators’ dinner to visit Jahn und Jahn, which presents Still Life by Remi Ajani. With thick brushstrokes, more or less diffuse contours and a very distinct visual style, the English artist contrasts floral arrangements and bodies dancing on poles, many with their heads turned down, contorted with the same delicacy, brevity and performativeness as the petals. Matthew Holman’s text — the artist had already told me about it — is, in fact, surgical in the reading he proposes of the exhibition based on the pictorial tradition of “still life” (if we were to think of it through the Portuguese equivalent term “natureza morta” (“dead nature”) , it would certainly open up further interpretive dimensions): her canvases capture fleeting moments of “these breathing, sweating things, summoned from some empty space”, “bodies held in precarious situations” that fold and unfold to “doing something extremely difficult as though it is the easiest thing in the world”. I leave the gallery wanting to see more.

I take a bit of a risk with the dress code for the evening event — “cocktail attire with a speculative touch” —, the official culmination of the VO opening weekend, at the Hotel Bayerischer Hof (where, over the first three days, a vast programme of talks, performances and workshops that challenge the discourses around art and politics has taken place under the title Too Soon To Say – The Unconference). I dance with everyone I met last year and this year, and I happily realise that I am building friendships. Another new old lesson — perhaps obvious, but always worth remembering: art, more than anything, is worth for the connections we make with people.

May 11, 2025, Sunday

I didn’t get much sleep, of course. Anyway, it’s the day to return from returning. My feet are already sore, but I’m determined to spend my Sunday walking: it’s the clearest and most beautiful day since I arrived, sunny and warm, and my last chance to witness life in the city. My flight isn’t until 8 pm, so I was able to squeeze in three more visits for today: to the Brandhorst Museum, the Haus der Kunst and the max goelitz gallery. (I already knew, based on my colleagues’ recommendations, that I would love the exhibitions in these three spaces.)

The first, Five Friends. John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, on display since April 10, makes it difficult to articulate any commentary. Difficult, precisely, because of its quality, so clearly and consensually manifest, both in terms of the masterful works of these names — so inventive and decisive for the history of the arts since the post-war period — and in the curatorial framing, supporting materials, and discursive structure.. If there we begin with silence, with white, with the interruption of movement or with nothingness — experiences so fundamental for the group of North American artists, in each of their preferred mediums — Shu Lea Cheang’s Kiss Kiss Kill Kill, at Haus der Kunst, invites us to excess. Hundreds of food boxes, computer keys, and words are poured out. Mushrooms reappear, constant and inspiring presences in many of the works I saw (equally appreciated, for example, by Cage, who collected them, or Laura Ni Fhlaibhin, who sometimes paints with mycelium powder), as well as the machines of a time of abandonment — recovering the tangible reality of an imaginary of progress that wants to be completely algorithmic and two-dimensional. There will be (or already are) many material ghosts which we must deal with. Alongside Cheang, this is what Philippe Parreno also shows in Voices. At the time of Various Others 2024, the same rooms were occupied by a retrospective of Rebecca Horn — now, they continue to be inhabited and haunted by objects with life, movement and rhythms of their own. As on the first day in Munich, I hear voices in a language I do not recognise, but this time, with an inaccessible, invisible, perhaps extraterrestrial origin. Parreno’s installations are mesmerisingly eerie — I almost feel afraid.

At max goelitz, I end my weekend of Various Others on a high note and a bit of humour. everything, entangled, all at once, by Julius von Bismarck, Anne Duk Hee Jordan and Haroon Mirza — a collaboration with alexander levy — is yet another of the gallery’s seductive shows. Highlights include Bismarck’s images — whose processes of “flattening” plants and animals, pressed between wooden or plastic vacuum traps, produce visual compositions that are as poetic as they are alarming and suffocating — Mirza’s sculpture at the entrance — which seems fragile in balance, yet powerful enough to move and generate energy — and Jordan’s bio-erotic film — which confronts us with the abundance of forms of pleasure in a “naturally” queer “nature”, and, using such a simple device, manages to establish itself as one of those artworks that we will never forget.

It’s almost 10:30 pm in Lisbon and we’re about to land. Tomorrow, I’ll miss the hearty breakfast, yes; but, above all, I’ll miss thinking as walking, with the certainty of wonder. I’ll look forward, with even more eagerness, to returning next spring.