Intervening on the Hexagon Pavillion designed by José Antonio Corrales and Ramón Vázquez Molezún, Alvaro Urbano both explores notions dreams & memory and reanimates Spanish histories in the construction of his own dreamscape: The Awakening [El Despertar]. The space exists within a kind of stasis – being at once in a process of growth and decay, these processes become convoluted; time is delineated and space disturbed and disrupted; the architectural structures being fragmented and pervaded by a yellow-hued mist rendering its boundaries non-existent in an endless, timeless dream.

Myles Francis Browne – For me, there is a certain irony in the title The Awakening. What we come to experience is a kind of dreamscape; therein implicating the viewer asleep both before, and perhaps within the space. Are we still asleep?

Alvaro Urbano – The title refers to the activating quality of dreaming, and points to the spatial performance which unfolds in the exhibition. You encounter a retelling of the story of the El Pabellón de los Hexágonos built in 1958 for the World’s Fair in Brussels.

MFB – Psychologically, dreams are a confluence between the conscious and subconscious minds. Does this dream serve as a means for escapism from an otherwise difficult waking world, or does it posit itself on a kind of idealist view for conscious reality?

AU – The “world of dreams” per se is interesting because it allows you to experience differently without a body or time. In the exhibition, I relate to the past and its hypothetical counterpart, the present, and the hypothetical future. As in a dream, these three stages merge. In the case of El Despertar, I wanted to represent what a parallel life of the Pavilion would be, including its desires, fantasies and failures – how a building could perform, speculate and tell us its story.

MFB – So too do dreams have the potential to communicate some desire that we might otherwise not admit to ourselves. Does the installation seek to provoke something perhaps repressed in its visitor?

AU – It’s interesting that you use the word “repressed” which fits very well with the history of Spain as a country that has a very complex path. El Despertar, as you know, is based on the Pabellón de Los Hexágonos, a building made to represent Spain for the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels. Spain at that time was under Franco’s dictatorship. Currently, the pavilion languishes as a ruin in La Casa de Campo in Madrid.

On one hand, the original architecture of the pavilion represents transparency and unusually sophisticated modern technology, something far from the values and the type of architecture that the Spanish regime was endorsing; For me, in this case, this “representation” was reversed, perverted, fictional and inadequate; yet simultaneously very convenient for the image of the country since the pavilion transmitted a very different and better “reality”.

In the 50s, Spain had a strong intellectual community with members like Corrales and Vázquez Molezún, the architects behind the pavilion. Upon researching the building, one can find incredibly interesting and bizarre stories. For instance, a group of artists with the architects and a curator planned an unusual and fantastic exhibition in the original pavilion for the 1958 exhibition. They wanted to leave it nearly empty as a space for contemplation with a black greyhound living in the space (called Felipe II), an orange, the capote of Manolete and the music of Manuel de Falla (a celebrated Spanish composer who didn’t share the same views as the government). At some point during the installation, the Spanish regime led by Franco found out and cancelled the original exhibition in Brussels. They fired the curator and replaced the original plan with more popular, cliché and less interesting material containing folkloric dances and objects.

I was born in Madrid 8 years after Franco left power. Somehow, the dictatorship and his figure had always been a sort of ghost in my upbringing and a period in the history of the country that still hasn’t fully recovered. As a kid, I remember using the old Spanish coin “pesetas” with the profile of Franco on them. Much like these coins, many monuments and fascist symbols have been disappearing and removed throughout the years, but the ghost still remains.

MFB – Has it provoked anything in you?

AU – Certainly yes. El Despertar is one of the more complex processes I have been involved in and it is a sum of many of my interests.

Since the very beginning, José Esparza Chong Cuy (the curator of the exhibition) and I thought about how to create a cinematographic experience, how to make a building or space perform. One important question was how to transform this exhibition into one infinite scene, one that perpetually changes with different emotions, faces and rhythms.

In my studio in Berlin, I worked with a team of architects and theatre set designers. For the music, I took part in a touching and beautiful collaboration with Juan Carlos Blancas aka Coeval, a Spanish composer, whose specialities are field recordings and computer sound transformations. For the exhibition, we created an immersive soundscape composition with an octophonic sound environment with several speakers hidden behind the sculptures, making them vibrate and transforming them into instruments. Thanks to a logarithm, a complex programming and computer coding the music generated in the exhibition is always changing with different accents, volumes, and chords. As a living organism, this newly conceived landscape made out of fog, light, sound, music, and sculptures is always alive; it always mutates.

The invitation from La Casa Encendida was a way for me to go back “home” since this is my first solo exhibition in Spain, Madrid in particular, where I was born and from which I left already 14 years ago. Next year, The Awakening will exhibit its second part in New York, at Storefront for Art and Architecture, in a city where I also used to live a decade ago. In a way, the second part of the project is another homecoming. We are planning to release an album in collaboration with Coeval with the music of El Despertar by then.

MFB – The Awakening seems to operate dichotomously; stratified somewhere between dream/nightmare, truth/untruth, authenticity/artifice. We oscillate between reality and fantasy until they become near indiscernible. How does this relate to the political context of the work?

AU – There are tangible objects in the space that refer to the censored exhibition in the 1958 Pavillion. However, also present is a soundscape partly inspired by Noches en Los Jardines de España by Manuel de Falla. In this soundscape composition, there are various layers made from different sources: environmental sounds, geophonic sounds such as water, wind and fire, electronic textures and biophonic sounds previously recorded from insects and other arthropods. Rarely in the exhibition would you be able to recognize these entities; like in a dream they exist as abstractions. Within every truth there are untruths, and history is exclusionary. Yet dreams and storytelling have a way of making their way into life, of having influence and potency.

MFB – There also exists this notion of animation, or perhaps re-animation which is central to the work. What begs these processes of re-/animation?

The question of animation and animism is always present in my work, the possible life behind a sculpture. Sometimes I recall my upbringing – I was educated in Catholic Spain where you are taught to pray to religious symbols and statues from an early age. As a kid I believed that I had the ability to talk and have real conversations with these sculptures, it was a world full of representations, spirits, beliefs and ghosts.

MFB – Surely this kind of intervention serves only to pervert the course of nature – a kind of Frankenstein’s monster that would have been better off putrefying rather than in permanent stagnation?

AU – I am interested in showing the life of an object, not in replicating something that already exists, but rather in imitating its life and bringing it into an environment that has the ability to tell a story.

In my installations, environments and sculptures there often exists a moment of deception, in that they work almost as clues of a constructed reality. For instance, cigarette butts on the floor can be traces of a person or dry leaves in a corner of a room an indication of a gust of wind. When these situations happen in a museum, an institution in which certain protocols must be followed, they alter reality, a subversive and even political action.

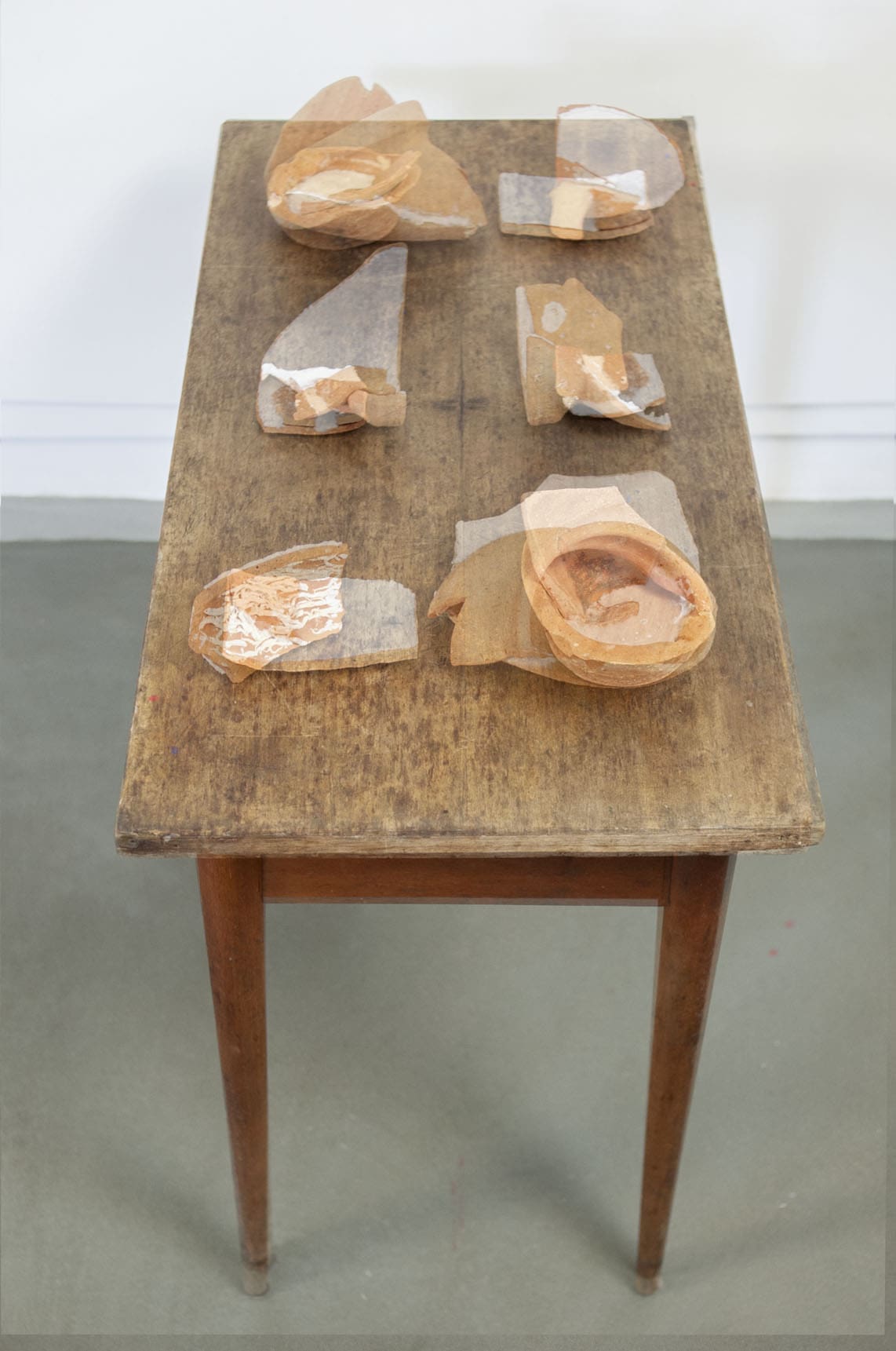

For the exhibition, I made around 1000 sculptures. Not many people realise that all the objects are constructed, but I think subconsciously they feel that something is contradictory, and this is a very interesting moment for me. The concept of fiction and fictional characters infiltrating reality is one that weaves through my practice.

In the installation, there are 2 raccoon costumes that lay on the floor, from a previous collaboration with Petrit Halilaj in 2016. Urban raccoons usually live in semi-abandoned spaces and survive off of human leftovers. Occasionally throughout the exhibition, the raccoon costumes are worn and thus become activated from time to time. In 1977, the Nippon Animation Studio in Japan created Raskal the Raccoon, which was a tremendous hit among kids. After the first episodes, the parents of these kids thought it was a good idea to import raccoons and have them as pets at home. Far from being a pet that someone could domesticate, raccoons are wild and potentially aggressive animals. Their unhappy owners began releasing them in nature, creating a strong disturbance in the ecosystem. It’s interesting to see here how an innocent fantasy could make its way through screens, ultimately producing a real-life ecological disaster.

In the case of El Despertar, we went so far as to make fictional film posters and put them up in the streets of Madrid. By advertising a film that doesn’t exist, the aim was to leak the fiction of the exhibition outside of the museum and into the real world, an invitation to an experience.

MFB – Parallel to the idea of dreams is this notion of memory, of remembering. Our memory itself is intervened with by invented impressions, sensations, and fictions. This is much like the space itself in The Awakening. What use does remembering serve if it is adulterated by these fictions?

AU – Memories are known to get foggy and are commonly adulterated with untruths; they are fragile. With El Despertar I wanted to represent this haziness in the materials I made the sculptures out of as well. The pavilion is an important reference to modern architecture in Spain, a unique building, one could even say, a rarity. A building that perhaps hasn’t been understood fully in the entirety of its cursed story, with multiple interesting layers, rumours and dramaturges. Storytelling, for me, is just another facet of memory, allowing dreams to form; an expansion of perspective and understanding.

The Awakening is on until 1 June, at La Casa Encendida, Madrid.