article

Writing Her Own Story

Koyo Kouoh is an example of curatorial excellence, learned on the job. Nothing predestined her to become the spearhead of contemporary African art.

Note: Koyo Kouoh passed away on 10 May 2025, at the age of 57. This article was written prior to her death. UMBIGO publishes this testimony as a tribute, highlighting the Venice Biennale's significant decision to maintain her curatorial project for 2026.

She is driven by an enthusiasm for the artists she champions—an enthusiasm that knows no bounds. The same goes for her team at the ZEITZ MOCAA contemporary art museum in Cape Town, which she has led since 2019. Whether it's Liesl Hartmann, head of mediation; Thato Mogotsi, curator of the current Nolan Oswald Dennis exhibition; or Rory Tsapayi, curatorial research fellow, she sweeps everyone along with her. No one remains indifferent, and everyone wants to give back that same energy. Her enthusiasm is contagious—her energy seems limitless.

One of Koyo Kouoh’s favorite words—who spent her youth in Zurich and is the next director of the Venice Biennale—is "celebration." The exhibition When We See Us was its clear expression. Presented first at Zeitz MOCAA, then throughout the entire Gegenwarts-Museum in Basel last year, it featured 208 paintings by 161 artists, exclusively showing scenes of celebration, rest, sharing, and joy within Black communities—be they African-American, Caribbean, or Sub-Saharan. The museum director loves to celebrate the pride of Black cultures, as seen at the Zeitz MOCAA Gala which draws an international crowd, just as she cherishes friendships in small gatherings.

One friend at the Gala is artist Otobong Nkanga, winner of Zeitz MOCAA’s 2025 Award for Artistic Excellence (her ninth award in ten years, including one at the Venice Biennale). She says she’s walked alongside Koyo since at least 2010, starting with the Make Yourself at Home exhibition at Kunsthal Charlottenborg in Copenhagen. “Koyo is very straightforward and transparent,” says the artist. “And when she doesn’t like something, she’s not afraid to say so. That’s how we’ve grown together and become friends.” Kader Attia, who participated in the same Copenhagen exhibition and was awarded the Marcel Duchamp and Joan Miró prizes in 2006, observed that the curator pays close attention to her dialogues with artists. “She is an exceptional woman,” sums up André Magnin, now a gallery owner in Paris. “She is determined and a free thinker. When I was attacked during a symposium at a Dakar Biennale because I was the only white person, Koyo defended me,” he recalls. “Her power of conviction is incredible,” insisted Parisian gallery owner Imane Farès in a Le Monde article on October 30, 2015.

Koyo Kouoh is fighting a battle against hundreds of years of prejudice, underestimation, contempt, submission, the deportation of tens of millions, exploitation, and even violence leading to torture and death, as seen in her adopted country, South Africa. Black Consciousness, the Black Arts Movement, or Négritude were artistic and intellectual movements formed in opposition to colonialism, apartheid, segregation, and racism. Today, it’s "Afropolitanism" that stirs minds. Launched by Taiye Selasi and championed by the brilliant theorist Achille Mbembe, it asks questions like: What historical processes have shaped the African continent and its peoples? What existing frameworks of thought are used when discussing Africa? For the Cameroonian political scientist who teaches in Johannesburg, the inhabitants of the African continent have always mixed elements from diverse cultures and beliefs, and even more so since the transatlantic slave trade. This new way of seeing and perceiving oneself resonates in Cape Town and across the continent, just as Northern nations, the world’s biggest polluters, refuse to compensate Southern nations for the increasingly disastrous consequences of climate change.

In 1989, the year the Iron Curtain fell in Europe and two years before the end of apartheid segregation laws in South Africa, Jean-Hubert Martin, a curator of a major Parisian exhibition, presented artworks from around the globe for the first time in Les Magiciens de la Terre, including many from Africa. The contribution came mainly from co-curator André Magnin, who subsequently built one of the largest collections of contemporary African art for the multimillionaire Jean Pigozzi. A little over thirty-five years later, the work of African artists is not only shown in Paris, London, New York, or Shanghai. On the continent today, there are more than a dozen biennials or triennials, several art fairs, and African artists continue to win prestigious awards, from the Golden Lion in Venice to the Grand Prix Images Vevey. Let’s be clear: speaking of "African artists" might seem arrogant to some—we're talking about 1.5 billion inhabitants! But that doesn’t matter to Koyo Kouoh. She is fiercely pan-Africanist and anti-nationalist: “Africa’s strength lies in its continental dimension. Little Senegal, little Tanzania, or little Kenya will never carry the same weight alone when facing global challenges, and not just in the cultural sphere.”

“Contemporary African art has always been contextualized through group exhibitions. This was necessary… for Africans themselves but also for the rest of the world. There was a need to catch up, and I participated in that…” Koyo Kouoh said in an interview with Jeune Afrique on July 16, 2022, concluding: “Today, I intend to prioritize retrospectives on an artist or a collective to highlight aesthetic genealogies and intergenerational influences, such as the Tracey Rose retrospective (shown after Zeitz MOCAA at the Kunstmuseum Bern in 2024). For now, no other institution in Africa can do this work. I say this without pretension. We are the only museum on the continent with so much space—some 6,000 square meters. Enough for us to be ambitious and generous!”

It’s true that the new conditions Koyo Kouoh established in Cape Town in record time are impressive. A polyglot, she has given Africa's largest contemporary art museum an international reach, reorganized the board of directors, found new donors, activated more sponsors, and at the same time re-energized a team worn down by the previous director, who had to pack his bags shortly after the museum's opening due to issues of sexism and racism. But above all, the winner of the Swiss Grand Award for Art / Prix Meret Oppenheim has defined the museum's direction, for which the title When We See Us (Lorsque Nous Nous Voyons) is a guiding principle. It refers to the Netflix miniseries When They See Us (2019) by African-American director Ava DuVernay, inspired by a true story of a miscarriage of justice due to racial prejudice. The title shifts perspective by replacing "They" with "We." From now on, the art collected, conserved, exhibited, theorized, and mediated at Zeitz MOCAA will primarily be art for a Black audience, exploring the Black condition, women's issues, neo-colonialism, and gender. This is what it means to take charge of writing one’s own story.

The art that interests the director is art that, like a sensitive seismograph, records the tremors of our histories,of history itself. “…an art that therefore goes beyond mere aesthetic appeal,” she told the German daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on April 1, 2011. It's the transformative power that interests her, its ability to change our thoughts and feelings, as she put it. Asked by the same newspaper about her ideal museum, eight years before her appointment, she said: “…it would be a museum whose architecture… becomes almost invisible, so that art can truly express itself, without being overshadowed by the building. It should also be open at night, and one should be able to stay there temporarily.” And in another context, still before her move to Cape Town, she expressed this wish: “…it should also be a museum that can move…, relocate itself constantly… Besides artists, I would also invite amateurs to exhibit things they believe in.” Today, Koyo Kouoh is radiant, having pulled it off: she heads a museum that doesn’t overshadow the art—former grain silos on Cape Town’s Waterfront. In a few months, the museum will travel to disadvantaged neighborhoods thanks to MOCAA Mobil—a project developed during COVID-19 and supported by a Lucerne-based foundation. And following the forced closure during the pandemic, the team devised an exhibition, Home Is Where The Art Is, that brought many Cape Town citizens, including many amateurs, to hang "works" from their living rooms—a public success. And sometimes people even live there: upon her arrival, the new director made 600 square meters of museum space available for artist residencies for Cape Town artists.

During our visit, artist Berni Searle occupied spacious rooms to display a portion of her work in a museum-like setting. The artist, who comes from a sculpture background, primarily uses photography and video, including for her new series that directly references the past of the grain silos and their maritime surroundings. The artist calls the series Sugarbaby and it refers to the women who entertained sailors ashore. To this day, Cape Town is a port of call on the vital sea route for trade between the east coast of Latin America and Southeast Asia. “This artist residency program in the museum is very important to me,” explains the director. “It allows artists to create significant pieces they couldn’t make in their studios. That was the case with Igshaan Adams. He produced the enormous tapestry he showed at the 2023 São Paulo Biennial here with us.” And with that mischievous smile she’s known for, she adds: “As a result, he didn’t want to go back home, he felt so comfortable here.”

Koyo Kouoh is very proud to have initiated a training program within the museum itself for young researchers, established with the University of the Western Cape (UWC). During our visit, Aindrea Emelife—the young curator who caught the art world’s attention with the Nigerian pavilion at the most recent Venice Biennale in 2024—is the curator of modern and contemporary art for the future Museum of West African Art (MOWAA), which she was presenting to aspiring curators. Aside from its very successful bioclimatic architecture, MOWAA’s conservation facilities—designed to house, among other things, objects stolen by colonizing countries like England—are impressive and put to shame all those European museum directors who drag their feet on restitution, claiming that "Africa doesn’t even have the means for proper conservation"!

Koyo Kouoh is a living example of curatorial excellence, learned on the job. Nothing predestined her to become the spearhead of contemporary African art. Born in 1967 in Douala, Cameroon, she moved to Zurich with her mother at the age of 13. During her job at Credit Suisse in Zurich, she became increasingly involved in NGO work supporting migrants and discovered the power of art as a way to reflect on social and political issues. Living between two worlds, she wanted to pass on this richness to her newborn son, Jibril, and in 1996, settled in Dakar—“definitely the cultural capital of Africa.” Twelve years later, in the same city, she founded Raw Material Company, a unique center for art, knowledge, and society, which has nurtured dozens of mediators and curators. Twice co-curator of the world's largest contemporary art exhibition, Documenta, she was appointed in December 2024 as the new director of the Venice Biennale for 2026.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

23 Jun 2025

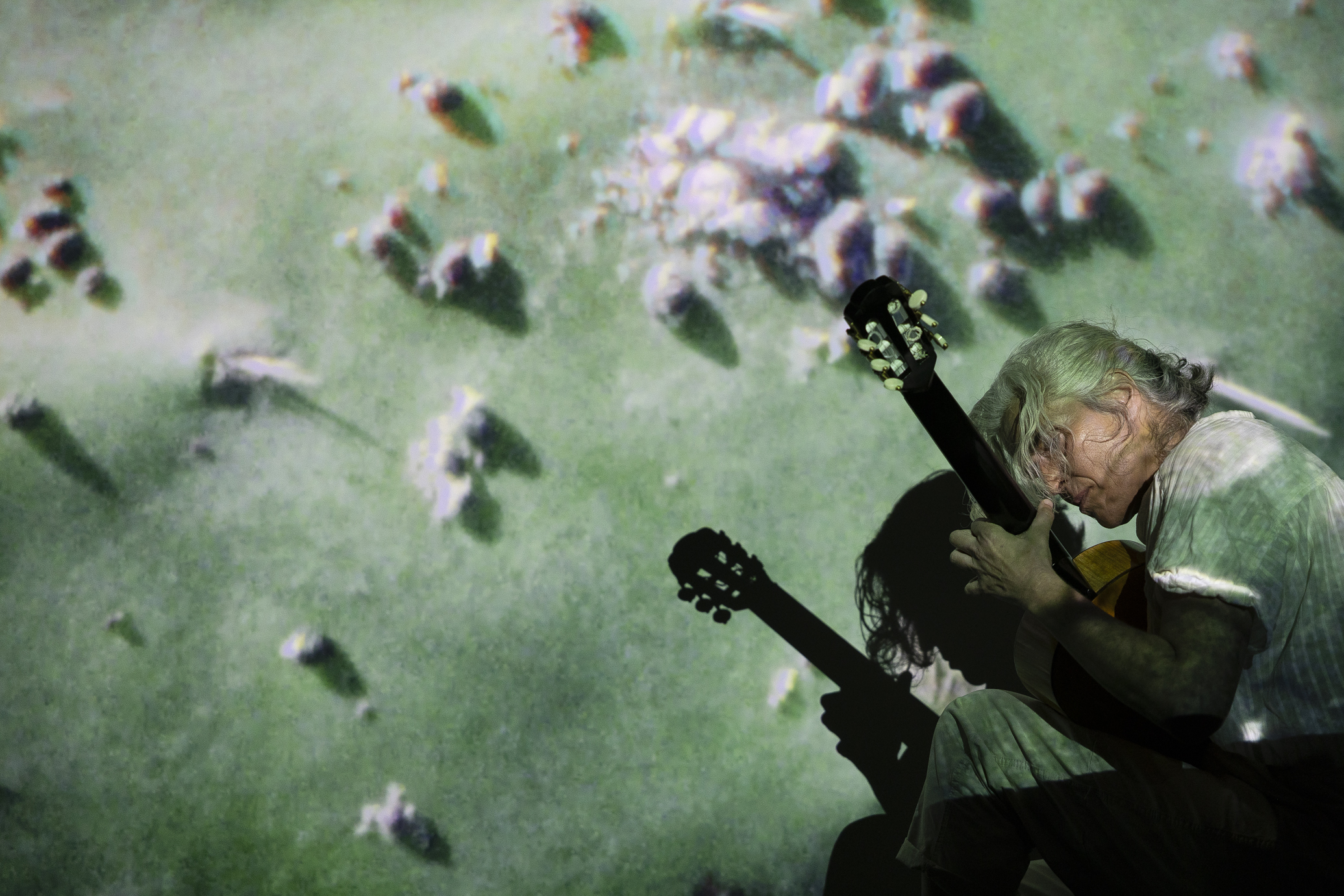

Lâmina da Lua: ritual as resistance

By Laurinda Branquinho

Next

article

26 Jun 2025

By Mafalda Teixeira

Related Posts

-poow5.jpg)