article

Forma Primeira, by Francisco Pedro Oliveira

“So, how are we to define this matter-movement, matter-energy, matter-flux, matter in variation that enters and leaves assemblages? (...) This matter-flux can only be followed. Undoubtedly, the operation that consists of following can be carried out in one place: a craftsman who planes the wood, the wood fibers, without changing location. (...) Let us therefore define the craftsman as the one who is determined in such a way that they follow the flow of matter, the machinic thread. The craftsman is the itinerant, the wanderer.It's intuition in action.”1

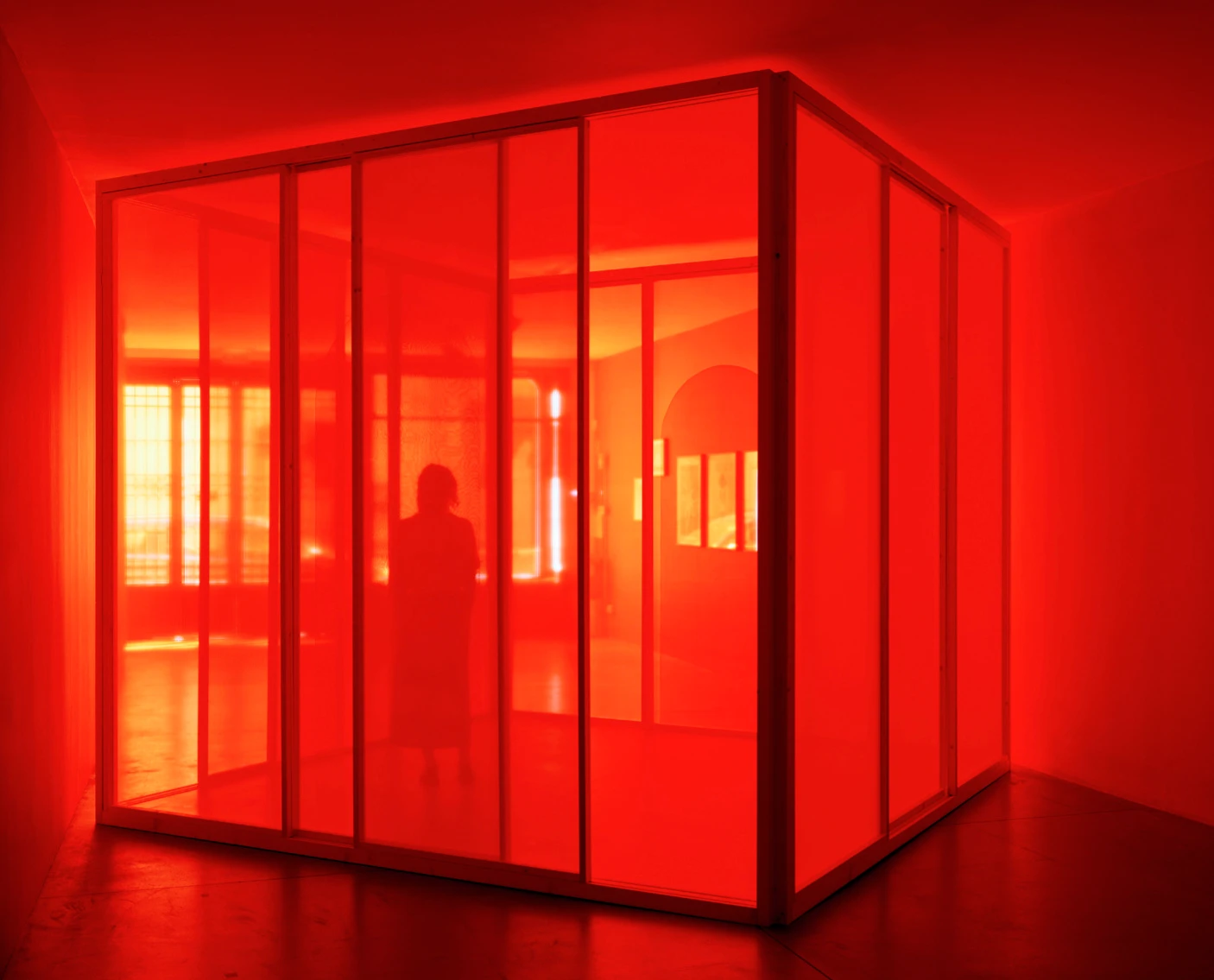

Francisco Pedro Oliveira’s exhibition, on view on Floor -1 of the Porto Municipal Gallery, is based on the title First Form. More than seeking or trying to unveil a first state, a task that would certainly involve other fields such as physics or philosophy, the artistic production presented here seems to unfold around the question as such, about the path around it, and the capacity to dialogue with it. Accessing a first form, which necessarily presupposes its existence, could coincide with the proposal of concrete form as such: sound, light, matter… Now, on the contrary, this prescription does not occupy any space, and if there is, perhaps, some first form, it will be the constant unfolding of the interaction between matter and artist (artisan). We see, then, three large stainless steel panels suspended and territorialized by engravings, illuminated by a single light source. In this sense, recalling the words of Deleuze and Guattari, if the artisan is necessarily the one who follows the matter, metallurgy occupies a particular place: “what metal and metallurgy bring to light is the life of matter itself, a vital state of matter as such, a material vitalism that undoubtedly exists everywhere, but is normally hidden or covered up, made unrecognizable, dissociated by the hylomorphic model. Metallurgy is the consciousness or thought of the matter-flow, and metal is the correlate of this consciousness.”2

These panels, marked by the act of welding itself, become agents like reflectors of the only light that inhabits the space, revealing reflections, colors and textures of the materials through which it passes. This light, even in the apparently empty space, creates a beam of dust that reveals its capacity to reveal what was previously unseen. In fact, in every exhibition, through a single source, this becomes explicit as the only way to reveal any element, not as a latent essence, but as a cut that reveals in the material a possibility of, in some way, being perceived and sensitized. In this sense, it becomes evident and palpable how each panel, intersecting the light beam in a different iteration of its path, reflects the light, and, therefore, forms itself as a perceived object in a radically different way. The metal and the marks secured on it only form as an image when the light, whatever it may be, inserts in them a necessarily contingent condition. If Francisco Pedro Oliveira writes that “it is done – only afterwards, does it acquire meaning”, the division between these two moments seems to be the point at which the work is inserted and for which light assumes the role of decisive agent. However, if it is in the light that we find the explicit element, the sound piece that also circulates the room projects itself precisely onto it: a first form that, when marked, reveals light, sound, metal; when seen, it becomes image and sensitivity. The notion of mark and the creation of objects also appear in Francisco Pedro Oliveira’s vocabulary, where the amulet assumes itself as this marked object, the result of a need to materialize a trace, which becomes free in the subsequent path. Deleuze and Guattari contextualize this dynamic in a similar way when they say that “these fibulas, these gold or silver plates, these pieces of jewelry, are attached to small mobile objects; they are not only easy to carry but belong to the object only as an object in motion. (...) Regardless of the effort or toil they imply, they are of the order of free action, related to free mobility, and not of the order of labor with its orders of gravity, resistance, and expenditure.”3 If labor is the captured activity, where the final meaning commands the act of creation and transformation, the amulet embodies the inversion that constitutes a marking that freely and repeatedly signifies itself.

The relationship between an expressive act that remains intuitive and an object that therefore remains free is also found in the constant oscillation between the abstract and the figurative, which constitutes nothing more than a limit established only at the moment of signification. Amidst the panels that occupy the space, and among the luminous stains and colors that form, the line, the point and the intuitive marking are concretized in faces and objects that in turn also fade into lines and points where clear delimitation is inconceivable. The creation of figures, images and concepts does not operate in the face of an objective of finding them concretely, but in the face of the intuitive contact between the artist and the material, constantly displaying its first form. It becomes clear how this inversion, the attribution of an artistic gesture to an intuitive marking, makes explicit a fundamental question: “Can this becoming, this emergence be called Art? This would make the territory a result of art. The artist: the first person to establish a boundary stone, or to make a mark.”, from which it follows that: “what is called raw art is not at all pathological or primitive; it is merely this constitution, this liberation, of materials of expression in the movement of territoriality: the basis or foundation of art. It takes anything and makes it a material of expression.”4 If the practice that inverts the logic of captured work, that refuses the search for a defined intentionality to be defined, asserts itself as artistic, the sensitivity to it opens up to a sensitivity to all matter, to the cosmos. It is notable how, in an exhibition where there would apparently be no movement, this appears, in an invisible form in the sound, and, above all, in the light beam, which makes explicit a movement that was already invisibly there, is always there. Referring to a cosmic scale, while coinciding with the invisibly small, the exhibition surrounds this movement that escapes the artist, which he only follows. Or, if the concept of artist makes sense in this context: “there is no imagination outside of technique. The modern figure is not the child or the lunatic, much less the artist, but the cosmic craftsman. (...) To be a craftsman and no longer an artist, creator or founder, is the only way to become cosmic, to leave milieus and earth behind. The invocation of the Cosmos does not operate in any way as a metaphor; on the contrary, the operation is effective, from the moment the artist connects himself to the material with forces of consistency or consolidation. (...) people and earth must be like the vectors of a cosmos that carries them away; then the cosmos itself will be art. From depopulation, to make a cosmic people; from deterritorialization, a cosmic earth – this is the desire of the craftsman-artist, here, there, locally.”5 The artist-craftsman becomes an agent of matter: the one who makes visible the cosmos that already exists, but which, with its light, can reflect something.

The exhibition is open until June 18.

1Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (2023) A Thousand Plateaus, pp. 474, 477. Tradução livre

2 Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (2023) A Thousand Plateaus, p. 479. Tradução livre

3 Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (2023) A Thousand Plateaus, pp. 467-468. Tradução livre

4 Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (2023) A Thousand Plateaus, pp. 368. Tradução livre

5 Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (2023) A Thousand Plateaus, pp. 401-402. Tradução livre

BIOGRAPHY

Mariana Machado (2000) was born in Porto and studied Cinema at Escola das Artes - Universidade Católica Portuguesa. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Digital and Sound Arts, also at Escola das Artes. She is an artist and researcher, interested above all in manifestations that articulate the moving image in a context between cinema and contemporary art, as well as the artistic potential of new technologies and their articulations with other materialities.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

Loop Lab Busan-7qk50.JPG)

03 Jun 2025

Loop Lab Busan: South Korea's new video art festival

By Julia Flamingo

Next

article

05 Jun 2025

Depth of Field by Mónica de Miranda and Deep Scarlet, Scream Ruby by Pauline Curnier Jardin, at the Galeria Municipal do Porto

By Rita Barqueiro

Related Posts