The Ergo Forte exhibition at the (A)Space gallery takes us first through an initial glimpse of the reverse side of a painting, which, according to its curator Frederico Vicente, reflects the intention of the exhibition to move away from the usual positioning of paintings and their natural fixation on the wall.

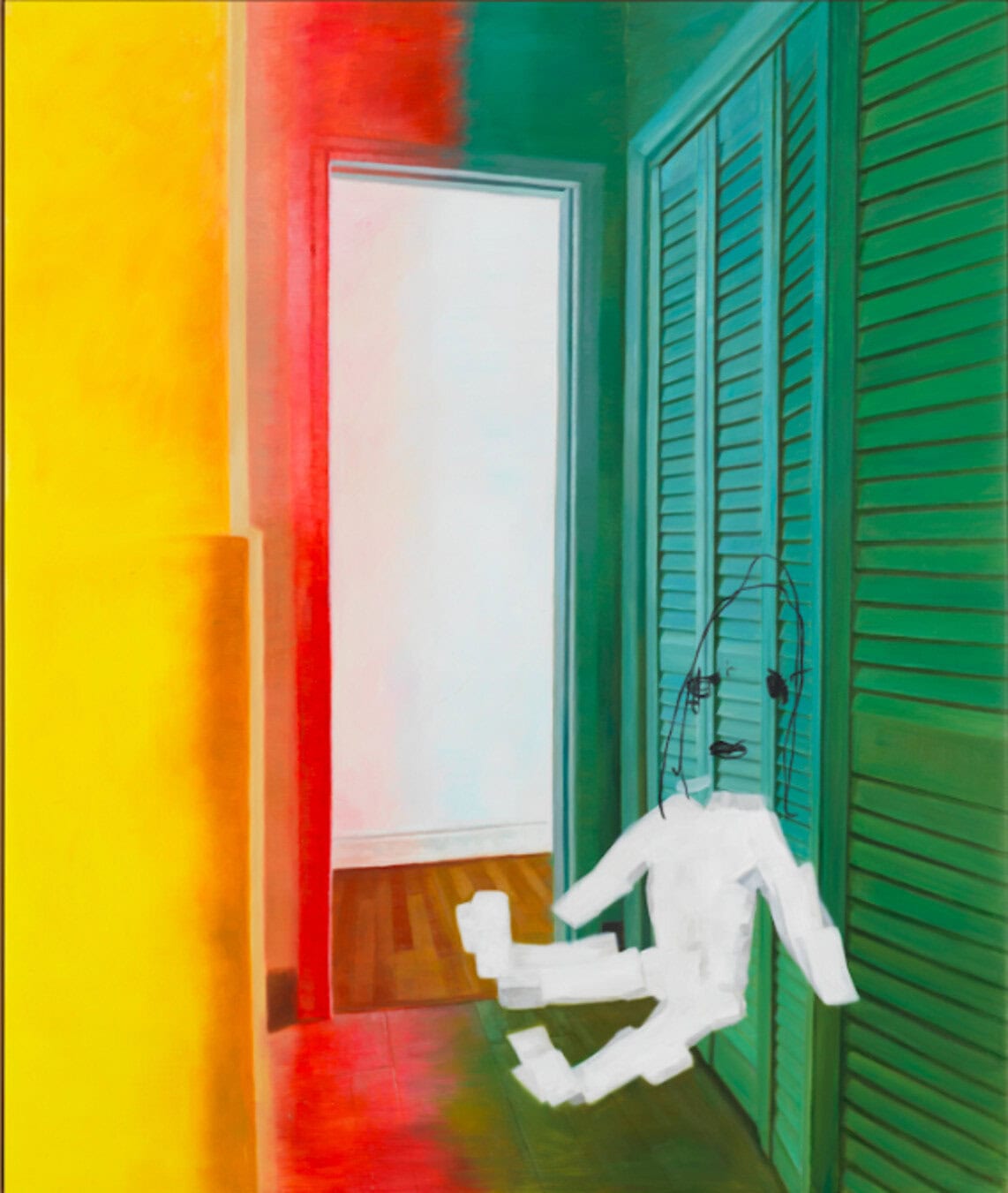

In a route unveiled by several paintings, marked by great pictorial masterful execution, Martinho Costa’s oil brushstrokes are unleashed on the wall, in a languid and succulent manner.

The different paintings, standing on their own, connect to each other, forming a cabin or a structure that wraps itself around or weaves itself into the gallery surroundings. The ceiling itself seems to be similar to the checkerboard effect of the paintings, which are supported and joined in an elaborate set of relationships. This reinforces the site-specific quality of Martinho’s exhibition.

The artist is attentive to detail.

The exhibition is intimately bound up with the gallery premises, with its stained or freshly painted walls, locked doors, corners, gaps.

Throughout the structure, made up of paintings positioned on top of each other or side by side, there are openings through which you can peek, or, behind them, see even more paintings, or rather, more reverse paintings, written in red, including dates, titles, or potential places where the works may have been made.

Following this rhythm, we uncover the ties between them and their antinomies.

In their fragile support, we find landscape paintings, small caves (perhaps), joined to other paintings that unveil wall tiles, followed by fallen plaster, or even small canvases with plant elements, together with paintings that represent the inner workings of a museum, where visitors are unknowingly depicted enjoying works of art.

Large-scale gardens are also featured on the canvas. They contain hidden traces of the urban and banal everyday life, like hoses, stakes and graffitied pillars. The artist’s eagerness to depict everything.

A painting of a wasteland is surrounded by other smaller canvases. There are plant details again, as well as people portrayed hunched over while working the land, mixed with images of modern furniture: upholstered chairs, harking back to a bygone era of industrialist sentiment.

In the largest room, an epitome imposes itself on a canvas: Fuck You I Won’t Do What you Tell Me. This is the phrase that welcomes us at the entrance to the exhibition’s second architectural structure, the cabin.

In the outer shell of the cabin, supported by paintings, we can see, and find available, its reverse sides. Covered in blue handwritten words. Between titles and dates of works, we can take a peek and see how much the structure reveals through its openings. New canvases are displayed inside. Martinho’s exhibition features more than 60 of them. We walk around the large structure walled in by canvases, step inside and are blown away by the vivid color and voluptuous form that the artist has accustomed us to.

As if in a garden of earthly delights and pleasures, we are lashed by a powerful fellowship of canvases that leave us astonished and thrilled. The interior overwhelms us with a series of canvases laid out vertically, reminding us of the old art salons in Paris. Not by chance, Frederico Vicente[1] mentions the Official Salon of the Paris Universal Exhibition, 1855, Courbet, and the Pavilion of Realism, in 1855.

One canvas contains a dog statue. It is golden and sphinx-like and stands straight, in contrast to a background covered by a wall of eighteenth century tiles. We then come across another canvas featuring the interior of a classical house. Other paintings follow, some showing patterns, almost abstract configurations, people in old museums, taking photographs, vegetation, architectural notes, decayed window grilles, walls with fallen plaster (again), and so on.

Martinho’s tendency towards archival images points to a set of references that are layered side by side in a journey that is not in any way linear, either in terms of narrative or meaning. Its discourse and exhibition rationale could be, as Eisenstein would describe it, and according to Georges Didi-Huberman, a “montage of attractions”.

An associative series of images, extending without seeming association, a set of arbitrary ideas, a melancholic resurgence of old artistic tastes, in communion with new ones, reminiscent of a history of art in constant mutation and permanent analysis. A somewhat lacklustre approach. An essay on culture, a Kulturwissenschaft.

The contrast between the various images and styles, the movement and rhythm they impose throughout the exhibition, is one of its major achievements and lasting features.

In every tone, every shape, every nook and cranny of the exhibition, Warburgian accents seem to emerge. Like a library, or hints of a visual anthropology[2], like a camera of curiosities, Wunderkammers, in a centrifugal, almost cinematic succession[3], rather Deleuzianized, and cinematographic[4].

A consistency and compulsion of the pathos of movement[5], or pathosformel[6], in an almost Benjaminian[7] reproduction.

Temporalities, anachronisms, consisting of cuts, montages, jumps, and surviving fossils, as Didi-Huberman would say.

The Ergo Forte exhibition is open until 22 March.

[1] Reference to the exhibition text of Ergo Forte.

[2] DIDI-HUBERMAN, Georges. “Foreword. Knowledge: Movement (The man who spoke to butterflies)”. In: MICHAUD, Philippe-Alain. Aby Warburg and the image in motion. English translation by Sophie Hawkes. New York: Zone Books, 2007, pp. 7-19.

[3] Ibidem

[4] Ibidem

[5] Ibidem

[6] Ibidem

[7] Ibidem