Aristotle said that art emulates nature and sometimes even completes it. Alexander’s preceptor also affirmed that, amongst its essences, art has features inherent to humanity: diegesis and mimesis, which are respectively discourse and imitation, narration and reproduction. These principles run through prehistoric, ancient, medieval, Renaissance and pre-Columbian art, and began to splinter in modern and contemporary art, following the limited Western historiography.

In 1911, when Ricciotto Canudo defined cinema as the seventh art, it incorporated much of the other arts. Filmmaking involves cutting out and using sound, video, writing, plasticity, art direction, architecture, craftsmanship, hands and machines that were once distinct and fragmented – all diluted together in a single structure intended to tell stories in a more or less consistent manner. The American playwright and writer David Mamet, in his book On Film Directing, put it very concisely: ‘that’s filmmaking, it’s juxtaposing images’. Filmmaking would then mean juxtaposing different techniques to compose images. Is every image a mirage?

Between July 10, 1998 and November 6, 2000, French-Maghreb philosopher Jacques Derrida granted an interview to Antoine de Baecque and Thierry Jousse, published in the issue number 556 of Cahiers du Cinéma in April 2001. Entitled Le cinéma et ses fantômes (The cinema and its ghosts, in English), the philosopher’s rare interview on cinema helps us to think of the seventh art as one that captures ghosts. The reason for this is that it captures/records the apparitions of the present, the same ones that fade away or change, stopping being what they once seemed. Derrida even identifies the filmstrip, through which the film was projected, as a ghostly component, laden with spectres, spreading ghosts.

Harmony Korine, known for exploring the depths of American underground cinema, is an American director, screenwriter and multi-artist best known for his films Spring Breakers, which he directed and wrote, Kids, for which he was screenwriter, and Gummo. The later ones were described by Folha de São Paulo, one of Brazil’s most widely read newspapers, as ‘controversial’. His solo exhibition, carefully curated by Agnés B at La Fab in Paris, features a rare essay on how filmmaking can loom over and spawn the synthesis and unfolding of cinema. In other words, the artist presents works that address ghostliness, the construction of a space, intervention/creation in/of reality, overlaying techniques and overturning hegemonic narratives on ideas and personas.

As we enter La Fab, walking through the La collection wing, we encounter a series of works by Korine displayed in such a way that they shift between the already mentioned ghostliness and the second crucial element for the artist’s cinema and production: space. The first four works on the left, entitled Orange Ghost, prominently feature a non-human form devoid of detail and with brushstrokes that produce a blurry effect. The piece in this series with the sharpest detail predates the others, which are always distorted, making confusion a pattern. The curator then cleverly presents us with The Golden Torques of Ulaid, a very grainy photo on which Korine painted and then photographed again. These interventions enhance the ghostly nature of the production with witch/wizard/ghost hats and orange shades, a colour that echoes the previous work and which, given the photographic clarity, could confuse us with the striking effect of thermal cameras, which theoretically detect the volume and movement of spirits. The tension between analogue, manual, digital, printing and hand-painting provides this exhibition with a heightened consistency, as it shows the dialogue between technical exercises, their findings and the visual and discursive proposals of the show and the artist.

White and Black Check, an oil and latex painting on canvas consisting of small black and white squares, is an elaborate composition designed to reveal a complex variation between shapes and volumes. This motion, obviously brought about by a mathematical study, is also connected to Malevich’s memorable Black Square, which he also called the ‘zero of form’ painting. Therein lied a black hole/square able to swallow up all the forms of nature. Indeed, White and Black Check bears a fantastical relation to chroma key, a surface on which any and all ‘forms of nature’ or figures can be projected and displayed after an editing process. Mini House Sitter 2, oil, latex and collage on canvas, appears next because of its rectangular, regular shapes and the linearity of its composition. The rectangles on a black background convey the recurring image of a house. As we step away from the canvas, we notice its resemblance to a bundle of negatives disturbed by the white paint splashed on the canvas by the artist, almost as if in a permanent effort to twist the images, distort reality and its sharpness or clarity. This bias can once again be seen in his mixed techniques, which are always more or less evident in his production. Collage in this work becomes an odd relationship with montage when made in an analogue way. This process used to involve gluing a square of film (filmstrip, reel) to the other section that would follow the scene. It was like putting together a jigsaw puzzle, a hand-made collage.

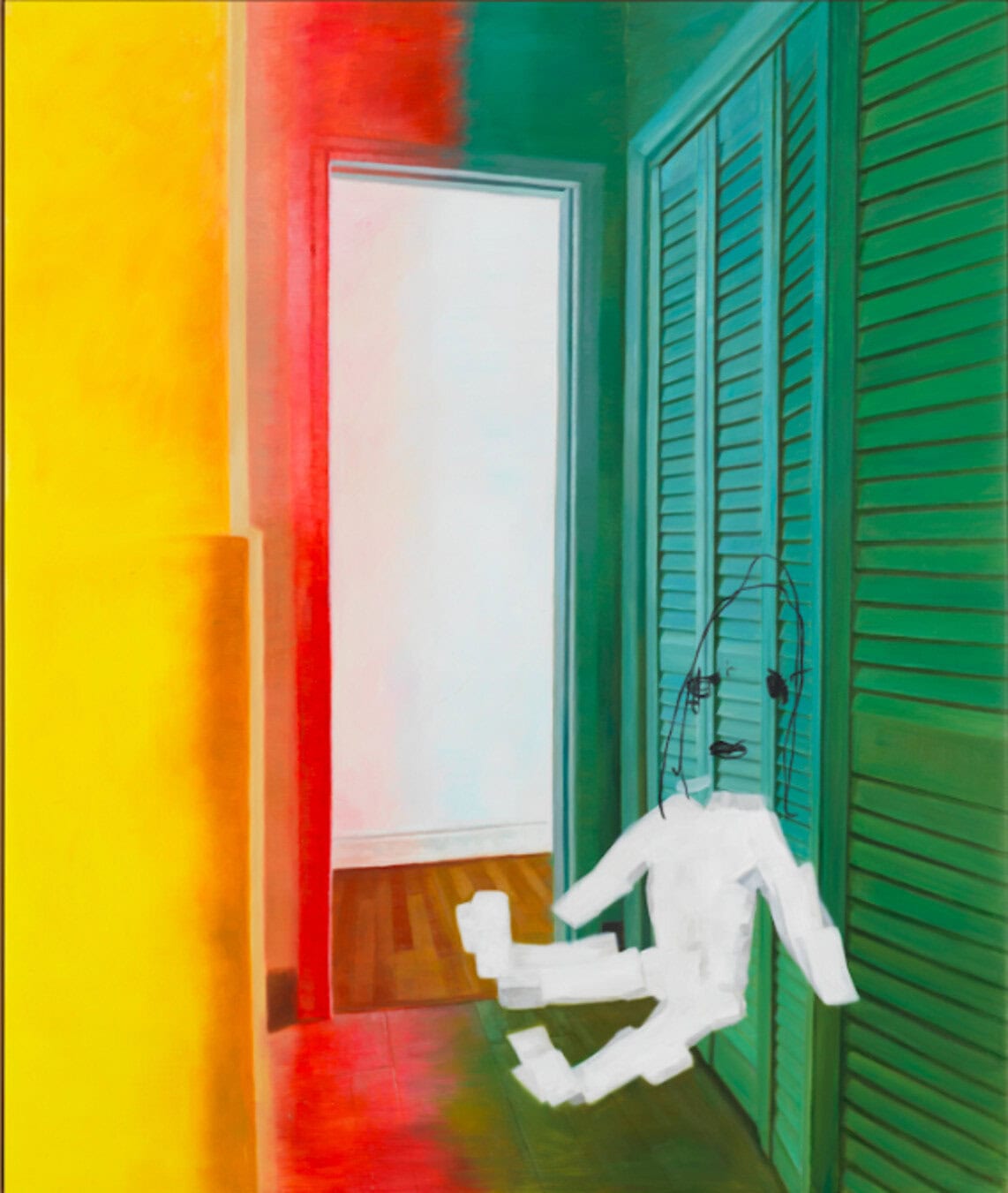

Partitioned off by the pillar supporting the La Fab building in Paris’s youthful 13th arrondissement, this piece is the least explicitly ghostly of all the works presented so far. The oil on canvas Twitchy Glue Boy guides us to a highly important and brilliantly ‘diluted’ point in the curator’s proposed route: space. The last work on the wall featured here is the only one that brings the space closer to realism and, on top of it, the delirium or ghostliness expressed by the ‘sketch’ of an almost human form (or ‘Banana de Pijamas’), in a clear representation not only of 3D animation, but also of rotoscoping, if we accept the artist’s lines as light experiments. In cinematographic terms, the more or less realistic setting with its detailed depth superimposed on a clearly unreal figure becomes more appealing when we read Christian Metz’s Film Language, in which the author states: ‘In conclusion, the secret of cinema lies in adding too many reality cues to images which, although they are enhanced in this way, are still perceived as images. Poor images do not sufficiently nourish the imagination enough to allow reality to be extracted from them. By contrast, the simulation of a fable by means as complex as reality – as is the case with theatre – always carries the risk of being nothing more than the all too real simulation of an imagination without reality’. This means that cinema tries to strike a balance between distance and proximity, the unreal and reality. As such, even fantasy has something real about it, at least in the imagination of the viewer.

It was precisely to confuse or disturb the memory of many spectators that Korine presents Devil Goat, a photographic installation marking the first of a number of other works that will feature Macaulay Culkin in absolutely opposing contexts to the brutal mythologising triggered by the success of the Home Alone saga, in which Culkin was the lead actor. The young actor fell victim to psychic ailments, possibly also caused by the notions of perfection and behaviour that he had to follow, as a consequence of his thunderous success and the brutal violence committed by the media profiteering that is common in the current capitalist stage. Contradicting the collective imagination (at least the admitted one), and in the sense of freeing or reversing this perfect symbol, Korine shows Culkin enjoying a meal with his mouth full, while sitting relaxed and shot from an angle that does not try to emphasise his beauty, for instance. We will also see pictures from the photobook the bad son later on in the exhibition, in which Culkin is shown looking less and less child-like. Harmony Karine also displays works that are derived directly from his work as a director and screenwriter, like The Milk Chicken Review series, a spin-off from his film Gummo, with photographic prints referring to analogue video prints. Some of the prints contain interventions (perhaps pen or brush strokes) in the characters’ eyes. Violence is even more clearly present in this series. Marguerite Saint-Quen writes: ‘the main characters suspended in time are the centre of the portraits: a boy pointing a gun, others with features that have been greyed out like those of criminals, one seen in the middle of the body, the other in a close-up. The oscillation between spontaneous poses and shots of characters in ‘depraved’ situations provides the vibration of the images. The same essay explains that “this series is rooted in Harmony Korine’s universe, which is particularly captivated by the culture of the southern United States. He grew up in Nashville and left for New York at a young age, but with his first film Gummo he returned to the South of his childhood.”

In line with his work, the curators also present some of the artist’s most recent pieces: a set of paintings made from the making of his film AGGRO DR1FT. Directed and scripted by Harmony Korine, it features Jordi Mollà and Travis Scott in the cast. Its plastic aspect, tapped into by Korine’s painting approach, is apparent in some of the film’s frames, particularly those shot with an infrared thermal camera. Attentive eyes may notice the outline of rapper Travis Scott on one of the screens. However, the most surprising element is the technical dexterity with which Korine succeeds in composing his work. Well beyond the fundamentals of depth, light and composition, the artist uses different techniques at different times to build a picture that remains whole. The layers, intersections and dialogues between techniques make Korine’s production incredibly consistent, breathtaking and wonderful. There are dialogues even in the most straightforward of works. Few of his works are not in some way formed by mixed techniques, such as cinema itself.

I propose a final superposition of works to form a dialogue with the immense mosaic of Harmony Korine’s wide-ranging artistic production. I’m drawing on Film Form, a famous book consisting of different writings by filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. The Brazilian edition of the book has a foreword by film critic José Carlos Avellar, who states in the foreword:

’For Eisenstein, cinema started to be invented long before it actually began to be invented.

Editing already existed in painting, (…) it already existed in theatre (…), it also existed in music, as we can see in Debussy’s and Scriabin’s experiments, similar to what can be done in a film with the wide-angle lens and telephoto lens; and also in prose, as we can see in Gorki, Tolstoy or Dickens; and in poetry, as we can observe in Mayakovsky or in Japanese verses such as,

A lonely crow.

On leafless bough.

One Autumn eve.

signs that the poet is writing with cinema shots and editing his poem just as a director edits his film, developing a new idea from the fusion/collision of independent shots’.

The exhibition is on view at the La Fab Foundation until 23 March.

-m8btp.jpg)