article

Mounira Al Solh, at Fundação de Serralves

Y’a Hamam Yalla Ma Tnam, Ma Tnam [O Pigeon, Do Not Sleep, Do Not Sleep] is the title of Mounira Al Solh’s latest exhibition at Serralves. By inverting the traditional logic of the lullaby, which normally soothes and protects, Al Solh imposes a cry of vigilance. From sleep to insomnia, protection to alarm, the exhibition's spirit condenses. What was tenderness becomes urgency. What was consolation turns into resistance.

Curated by João Mourão and Luís Silva, the exhibition is constructed as a space of suspension where trauma is filtered through small gestures of care: sewing, embroidering, wrapping, drawing. The exhibition articulates different artistic practices and mobilizes a fictional, sometimes allegorical language, to access experiences that resist direct naming. It is not about reconstructing a linear narrative, but about welcoming and scrutinizing that which, while intimate, is also historical and collective.

With traces of a naïve aesthetic, childhood occupies a central place, not as an angelic space, but as a territory permeable to fear. A fear that, stripped of metaphors, manifests itself as instinct. The narrative that guides the exhibition recognizes the simultaneity between vulnerability and lucidity. The child who inhabits that space is a body that, intercepted by conflict, sees in acts that require patience a form of escape. Subject to loss, the child transforms fear into gesture.

In a logic of care and mending, Al Solh constructs a visual language that is simultaneously affective and political. Notions such as home and childhood are given prominence: not as idealized spaces, but as territories marked by fragility and persistence. The lilac-toned walls soften the light, while children's voices, singing lullabies, punctuate the visitor's path. Clothes hanging out as if in domestic courtyards show marks: holes, patches, scars sewn with children's drawings. They are traces of a gesture that insists on repairing. Here, the act of sewing is more than manual labour: it is a way to keep going.

Thus, between the personal memory of childhood in Beirut and the collective catastrophe of forced migration, Al Solh constructs a visual lexicon in which pink, black and naïve lines coexist with packhorses whose travellers have been deprived of identity. The presence of the word, in Arabic and English, drawn in freehand lines or inscribed in speech bubbles, does not function as a mere caption. Ambiguous and fragmented, it inscribes the linguistic multiplicity of the migrant subject.

There is a form of hope that does not retreat in the face of violence, and it is in this space that Han Kang’s words resonate when, in Human Acts, he writes: The thread of life is as strong as the tendon of an ox. The tendon is neither fragile nor volatile: it is hard, fibrous, and resistant to tears. Invisible, but essential, it is what sustains movement. And as a physical archive of oppression, the figure of the ox emerges – the one that endures, carries, resists, like so many bodies silenced by war, migration, and the history of time. Although the figure of the ox does not appear explicitly in Al Solh, its symbolic force resonates in the bodies that the artist summons.

Thus, despite the violence that tears apart bodies and memories, an insistent, invisible force remains, sustaining the gesture of continuing. It is this force, silent and persistent, that the artist summons in each patched fabric. A repeated act of reparation, begun in childhood, during the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990), and which, after the explosion in the Port of Beirut in 2020, took on a new dimension by becoming collective. This gesture then began to be shared with a group of Lebanese and Dutch women, including migrants, who, by tearing and patching their own nightclothes, shared stories of loss, persistence and care.

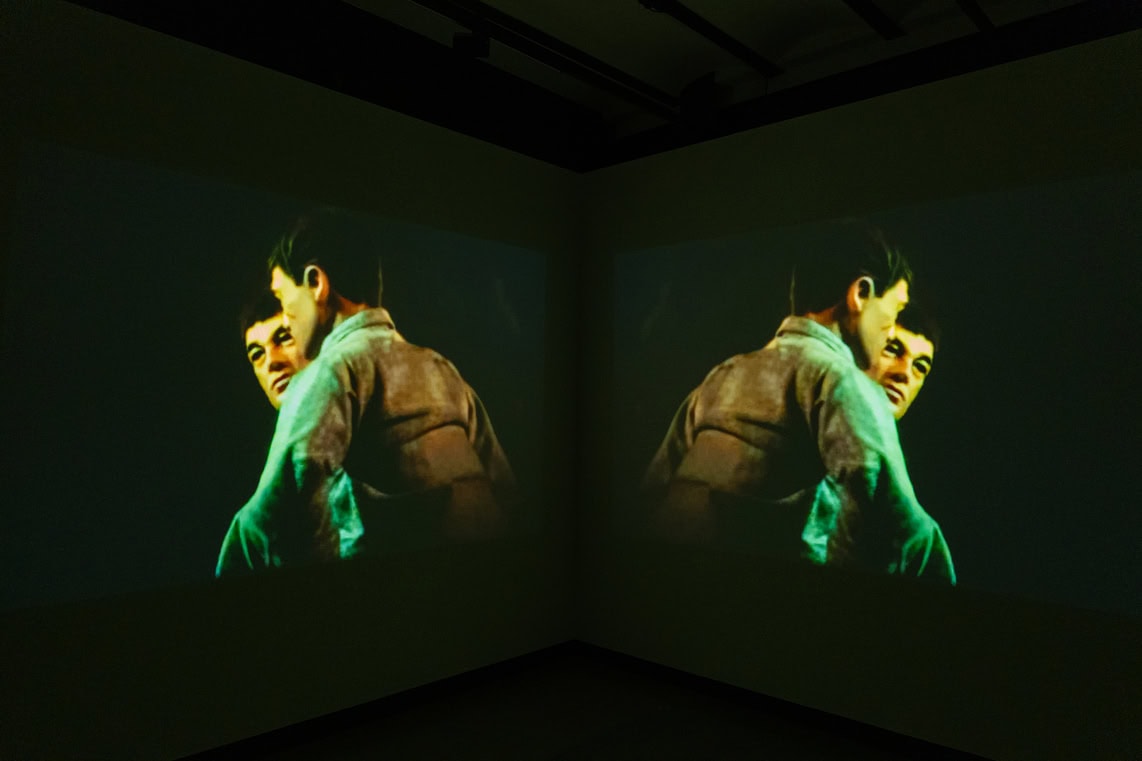

We see these clothes hanging out as a metaphor for the arbitrariness that structures the effects of violence. But it is also between these pajamas that, at the end of the exhibition, we see projected the child who had been with us until then. However, now she appears metamorphosed: a subject on the run, a lucid consciousness, a body that acts and resists.

After all, narrating is already resisting.

The exhibition is open until August 31.

BIOGRAPHY

Débora Valeixo Rana (b. 1990, Lisbon, Portugal) is a philosophy teacher living in Porto. She graduated in Philosophy from the Faculty of Letters of the University of Porto (2011) and has a Master's degree in Teaching Philosophy in Secondary Education (2019). Her academic and professional career reflects a deep interest in the intersection between Art and Philosophy, a dialogue that led her, in 2022, to take up a master's degree in Artistic Studies and Art Criticism at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Porto.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

22 May 2025

Vital and Virtual Energy at Tejo Central

By Wilson Ledo

Next

agenda

-f2kgu.png)

29 May 2025

By Umbigo

Related Posts