article

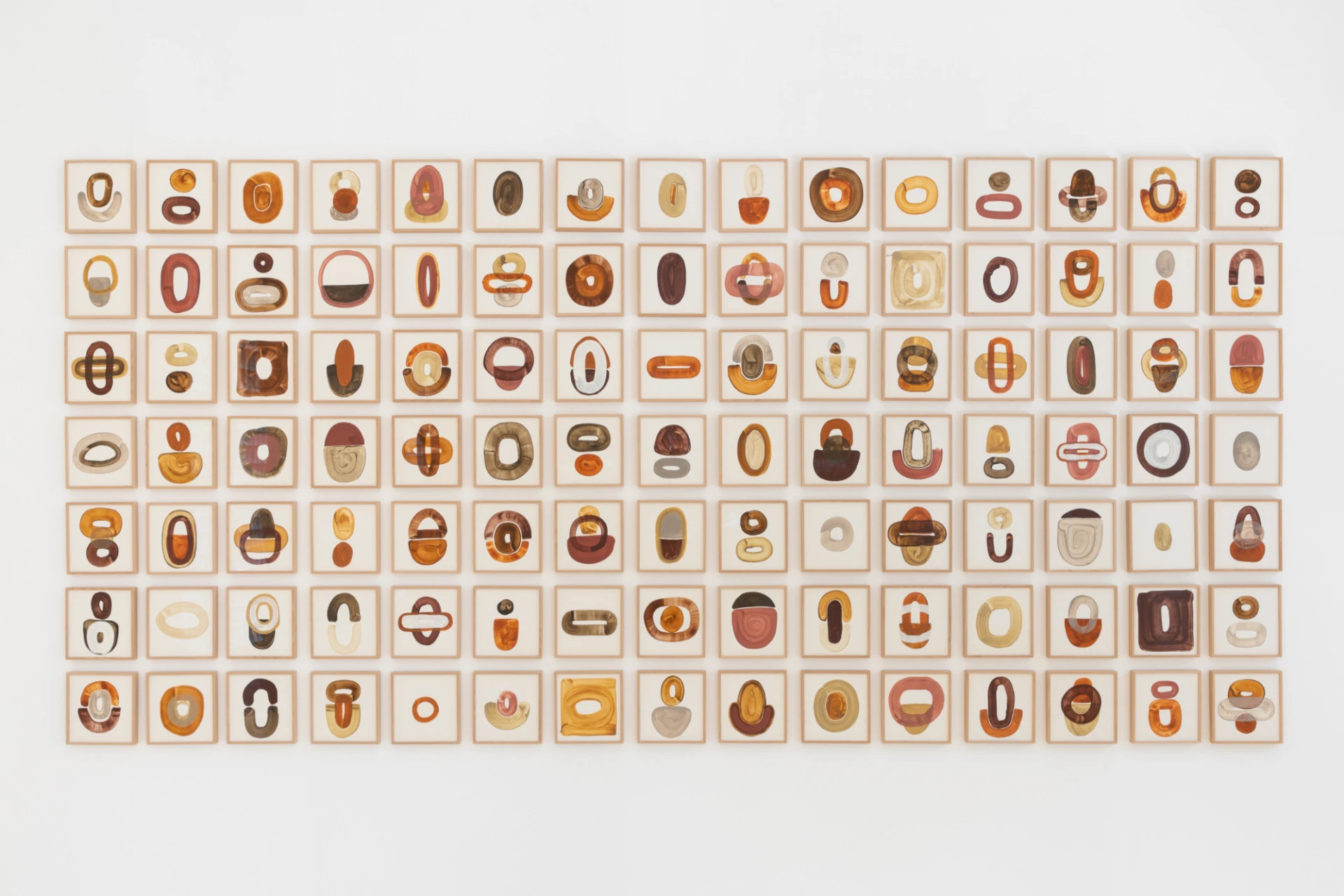

Mute Track, by Bianca Hlywa

Those familiar with Bianca Hlywa’s work will find in "Mute Track", on display at Sismógrafo in Porto, a coherent extension of her artistic practice.

Known for her monumental installations created with SCOBY (Symbiotic Culture of Bacterial Yeast), the artist once again repeats her formula, which remains as relevant and impactful as ever. While the use of these bacterial cultures to produce kombucha is already recognizable to us, their transposition into an artistic universe creates a discomfort that is both repulsive and fascinating.

We have not yet entered the exhibition when a mass of air, laden with an acidic, pungent and vinegary odour, enters our nostrils. This is the first indication of a living organism that inhabits it. In the centre of the exhibition space, two large SCOBYs, roughly sewn to a grid of synthetic fabric. Their tones between beige, green and fermented brown, combined with a viscous and fleshy texture, evoke images of the interior of the human body, suggesting membranes, viscera and putrefying fatty tissues. A disturbing strangeness emerges that Freud would describe as uncanny[1]. This organism is not human, but it is not another either – it’s a body that could be inside us, that perhaps is, after all, part of us. A kind of abject, as defined by Julia Kristeva in Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection: that is neither subject nor object, but that threatens us precisely because it resides on the threshold of both classifications. It is precisely on this border, between the self and the other, the human and the non-human, that Mute Track operates.

The installation also gives way to a hypnotic choreography – a cadence of repeated gestures, precipitated into a mechanical automatism. Attached to a structure of scaffolding and industrial rotary motors, the SCOBYs start from a resting position and gradually increase their speed. They alternate between slow rotation and abrupt acceleration, in a continuous cycle programmed to repeat every six minutes. The material follows this movement, leaving a wet trail that spreads in concentric rings across the gallery floor. The intermittent, metallic sound of the motors punctuates the space with rehearsed precision. From time to time, a dripping sound – irregular and almost imperceptible – can be heard, interrupting this mechanical rhythm. The installation seems alive: not because it moves, but because it imposes itself with its own cadence, a pulsating and unpredictable presence. A latent tension thus stands out between the fragile, organic bodies of the SCOBYs and the robust metal of the mechanisms that support them. The machine seems to allow these bodies to remain alive and, at the same time, wants to tear them apart at every moment.

In a liminal state between flesh and steel, integrity and collapse, the installation evokes an ambiguous scenario. Are we in a laboratory or a butcher shop? In a sanctuary or a biotechnological waste dump? The title of the exhibition, Mute Track, suggests its paradoxical nature from the outset. The term ‘track’ presupposes a path, a displacement—perhaps even a sound path, a music. In turn, the word ‘mute’ describes a silence, a sound suppression. There is a suggestion of absence that reveals itself as a listening to what remains unclassifiable, in a disconcerting in-between space given over to silence. In times of absolute domestication of the world, Mute Track is above all a primary, almost ritualistic, encounter that silently confronts us with our own corporeality. It tells us that we are also matter, that there is something of us in those suspended organisms. And that, ultimately, the world, out there (or in here), like a bacterial culture, never stops growing, with or without our permission.

Previously shown at St. Chads, London, Mute Track is on display at the Sismógrafo until the 26th of July.

[1] The Uncanny (1919), S. Freud

BIOGRAPHY

Maria Inês Mendes is studying for a master's degree in Art Criticism and Curatorship at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Lisbon. In 2024, she completed a degree in Communication Sciences at the NOVA University Lisbon. She writes about cinema on CINEblog, a website promoted by NOVA's Philosophy Institute and completed an internship at Umbigo Magazine, where she continues to publish regularly. She also collaborates with BEAST – International Film Festival.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

27 Jun 2025

The Condominium and other forms

By Filipa Nunes

Next

article

02 Jul 2025

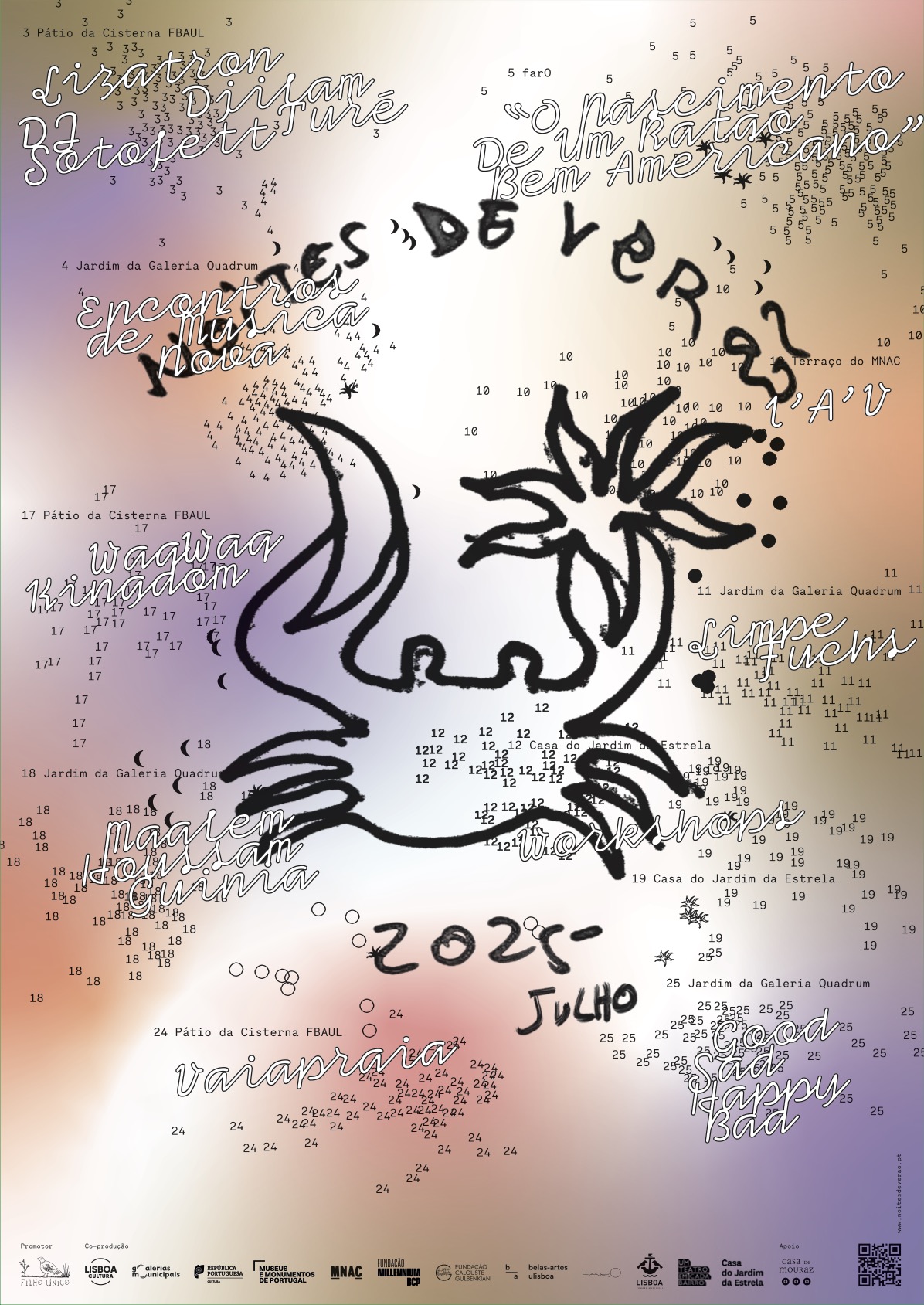

Noites de Verão 2025 kicks off on 3 July in Lisbon

By Umbigo

Related Posts