article

A(na)tomic unity: Vieira da Silva at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

In October, I traveled to the Basque Country for the opening of the exhibition Maria Helena Vieira da Silva: Anatomy of Space, on display at the Guggenheim Museum until February 22, 2026. While the exhibition had already been presented in Venice between April and September 2025, its presence in Bilbao continues a close relationship between the museum and the artist, whose pieces were acquired by Peggy Guggenheim and included in her exhibition 31 Women, held in New York in 1943.

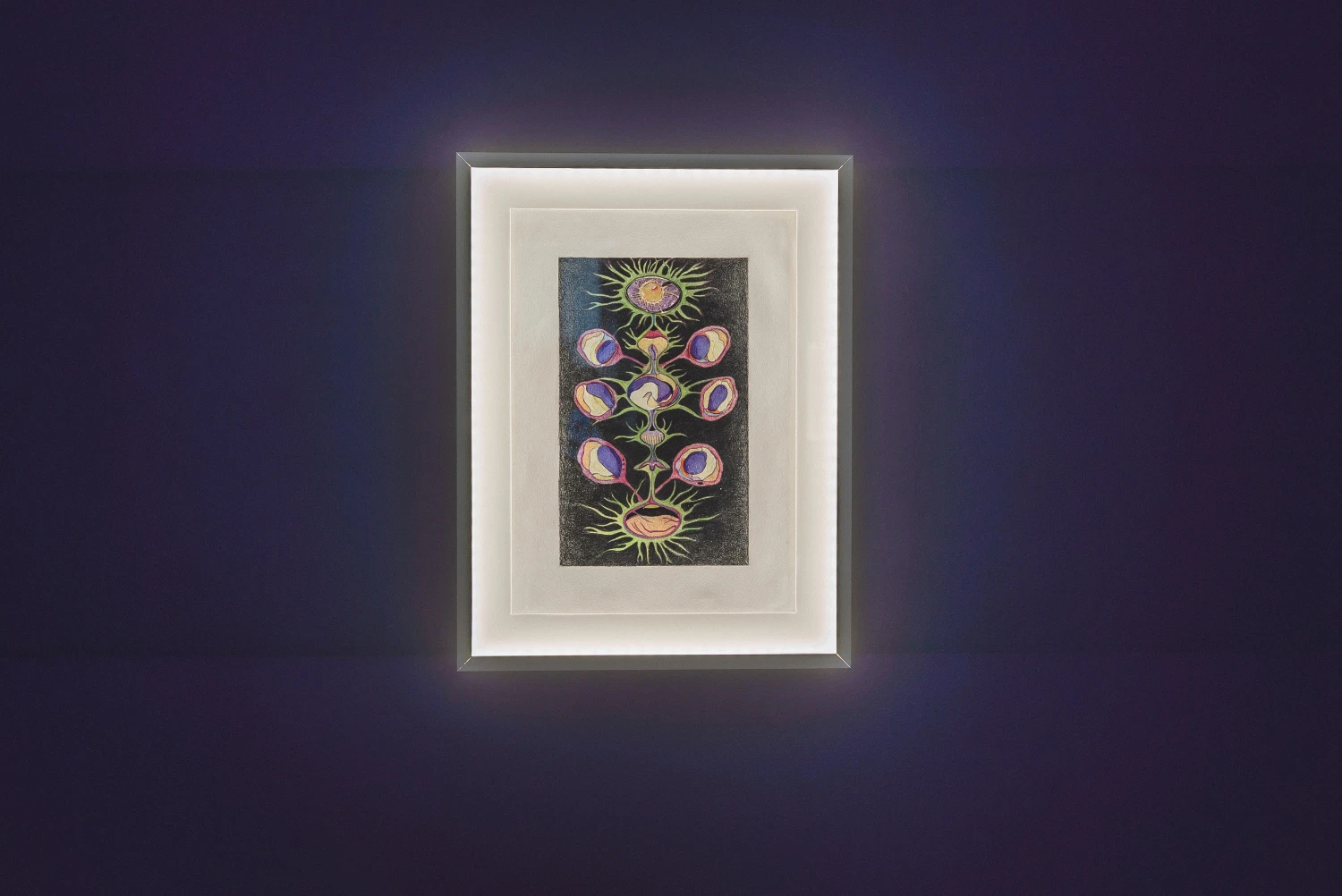

Curated by Flávia Frigeri, Anatomy of Space brings together approximately 70 works by Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, attempting to chronologically outline the evolution of her pictorial language – always permeable to its own time, but never entirely absorbed by its references. Abstraction, the curator explains, was a conscious decision for Vieira da Silva, a path traced at her own pace. And it is precisely in clarifying the maturation of her artistic language, achieved through various curatorial decisions, that a substantial part of this retrospective exhibition resides. Therefore, the text I write will inevitably follow the narrative sequence of the exhibition.

So, let's start at the beginning, which is where – I've heard – things should begin. We enter the exhibition and are greeted by the first exhibition section dedicated to presenting the artist and contextualizing her work. Here, we find Vieira da Silva portrayed by herself in Autoportrait (1930), and by her husband Arpad Szenes in Portrait de Marie Hélène (1940). We see her immersed in her creative process – slow and meticulous, almost surgical – and we also observe the interior of her studio, which was simultaneously a workspace and a recurring motif in her paintings. But it is in Denise Colomb's photograph (Maria Helena Vieira da Silva in the Studio, 1948), which occupies a prominent wall in the exhibition space, that the exhibition's theme seems to be launched. The image shows the artist in her Paris studio, surrounded by her books, objects, and some still-incomplete paintings. With numerous overlapping layers, the photograph presents the artist multiplied and projected onto the studio space. Several facets of Vieira da Silva are found here. And it is significant that the first image in the exhibition shows us these various versions of the artist. Because, ultimately, what the exhibition proposes is precisely to reveal the multiple conceptual and formal layers that make up her artistic language.

But what layers are we referring to? A second exhibition core leads us to Vieira da Silva's initial understanding of space and abstraction. In La Chambre à carreaux (1935), for example, we see a room formed by squares and rhombuses that suggest a rhythmic composition of colors. The piece, which refers to an early phase of her career, introduces what would become the guidelines of her work. The interplay of perspective and color in service of the representation of space is revealed, as well as the influence of the Portuguese decorative tradition, clarified by the use of tiles as a constructive module. In turn, Marseille Blanc (1931) marks the moment when the artist became interested in the geometry hidden in the urban fabric – those lines and geometric constructions that, in such a simple way, capture the essence of space. I then return to what I had previously written about Fred Sandback's exhibition Alinhavando o Espaço. At the time, the text I wrote dealt with a series of linear constructions on display – sculptures that, within the limits of possibility, were stripped of their weight and mass. I remember the exhibition rooms almost empty, with wires that crossed, intersected, and organized the space, and I find this same cartographic exercise again in Anatomy of Space. Interested in mapping space and reducing it to an anatomical structure – lines, planes, and perspectives – Vieira da Silva also seems to be aligning space.

This cartographic exercise becomes particularly evident in Cities: Real and Imagined, which brings together many of her works on the structure and skeleton of space. In this regard, it seems pertinent to recall that Vieira da Silva attended some anatomy classes at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Lisbon. Contrary to what might be expected, these classes did not contribute to an improvement in her figurative technique, but they traced a path towards abstraction, which would be revealed in the way the artist represented urban centers. Sometimes, her paintings remind us of the cities that have shaped his personal imagination. We see the warm lights of Paris reflected on the Seine River; the bluish tones and triangular shapes that remind us of the gondolas of Venice; and the buildings stacked on the hillsides of Lisbon. We see all this, and yet nothing remains but our intuition to allow us to confirm what we see. At other times, her paintings show us cities that are more (than the) existing ones: other places, outside of time and space, that condense within themselves observations and details that resonate in all other cities. In Livro do Desassossego, Fernando Pessoa writes: What is universal in the Santa Justa Lift is the mechanics facilitating the world. What is true in Reims Cathedral is not the cathedral nor Reims, but the religious majesty of the buildings consecrated to the knowledge of the depths of the human soul (p. 134). He also tells us that in our experience of Earth there are only two things: the universal and the particular. To describe the universal is to describe what is common to every soul and every human experience. To describe the universal of cities is, therefore, to use what is common to our experience to weave abstract impressions of space.

In Vieira da Silva's work, feelings of alienation and confusion stand out: a sense of disorientation that permeates his labyrinthine constructions. In the piece La Ville Tentaculaire (1954), for example, the city is represented as a tentacular organism that envelops us. The vertiginous lines, which cut across the canvas like cracks or wounds in the city's fabric, seem to foreshadow an imminent collapse. And the labyrinthine forms, where the gaze gets lost, reveal a system as destructive and cryptic as it is captivating. The same applies to his representations of internal and external spaces, where the transitional environments—the hallways, the stairs, the corridors—suggest the fragility of the urban fabric itself. In these geometric constructions, there is the imminence of an abyss, but above all, the feeling that urban space is in constant mutation, threatening to disappear or disintegrate. These are, after all, the universal impressions of a city, and it is impressive that, however fragmented or abstract it may be, Vieira da Silva's painting is sufficient to evoke in us a feeling of immersion in an urban reality.

If Cities: Real and Imagined refers to the artist's understanding of space, Checkers, Dancers and Chess Players highlights her work on movement. In this core – where some of her most notable works are gathered – the spaces represented are, above all, spaces in motion. In the works included in this set, some figures become an integral part of the architecture: they are the ones that activate the space and that, with it, move, distort and vibrate. In Ballet ou Les Arlequins (1946), we see some harlequins that seem to dance, dragging with them the tiles that make up the background. In turn, Danse (1936) and Les Grilles en Émeutes (1939) show us some figures that move on a geometric grid. Note how these canvases reveal the movement of the figures imprinted in the undulation of the tiles, and how this dynamic also introduces a subtle temporal dimension, albeit inscribed in the very construction of the image.

The time of Vieira da Silva's canvases is, above all, the time we linger over them (Her pictures no longer empty themselves at one single instant, but play themselves at their own speed, the eye being carefully directed through the intricacies of their elaborated structure.). As we have seen, her paintings have become progressively more complex and more time-consuming. If some figuration persists at the beginning of her career, increasingly dense labyrinthine grids emerge towards the end. In any case, there is a reflection on the anatomy of our experience – undeniably anchored in time and space – that runs throughout her artistic journey. Perhaps that is why Anatomy of Space closes with a core that brings together a series of canvases around the color white. Ending with white – this element repeated in her canvases – not only highlights the evolution of the artist's understanding of abstraction, but also suggests a return to an a(na)atomic unity of pictorial matter, mirroring what Vieira da Silva's work has actually been throughout the decades.

Umbigo travelled to the Basque city at the invitation of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

BIOGRAPHY

Maria Inês Mendes is is studying for a master's degree in Art Criticism and Curatorship at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Lisbon. In 2024, she completed her degree in Communication Sciences at NOVA University Lisbon. She has written about cinema on CINEblog, a page promoted by NOVA's Institute of Philosophy. She is currently responsible for UMBIGO online, where she publishes regularly, and collaborates with BEAST - International Film Festival.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

26 Nov 2025

The first Bukhara Biennial - Recipes for Broken Hearts

By Katya Savchenko

Next

article

27 Nov 2025

About Cynara Complex: Diana Policarpo at VNBM Arte Contemporânea

By Daniel Madeira

Related Posts