article

Prolonging the encounter: Anas by Gäetan

Ricardo Valentim organizes and hosts at his home Anas, an exhibition of portraits of Ana Jotta by Gaëtan. There are numerous parallels and connections between the two, friends from the time they both briefly spent at ESBAL.

A first glance at Gaëtan's work seems to give us an idea of its subject matter, but perhaps it misleads us in our apparent perception of its totality. Self-representation, an absolute focus since the early 1990s, present almost from the beginning, was sometimes accompanied by other subject matter. However, before portraiture, Gaëtan turned to paper. For Galeria Módulo (Porto) and later at the National Gallery of Modern Art, in 1977 and 1978, he created several Desenho-objeto, a series of constructions in twisted paper and sisal rope, which, intertwined, minimal, and vague, attempted to create subtle disturbances in architecture. Moments of fickle artifacts and near-erasure for Gaëtan, who restricts himself to the figure.

In 1979, at the collective exhibition Arte Actual Portuguesa, the artist hung two large sheets of wrapping paper, like deflated, suspended cones. If in this effective gesture one can sense an approximation to Robert Morris's sculpture, and in the material experimentation of Desenho-objeto perhaps a glimpse of Richard Serra's Verb List strategy emerges, one understands, by exploring these preambles, that Gaëtan was punctual and precise in his interventions. Working on paper without graphite, oil, or any other intermediary for his hands and body, he seems to be preparing the support for the future design, not so much through purification, but by apprehending it and making himself understood, in rituals that, though obscure, were certainly more magic than exorcism. In the same year, in his second solo exhibition at Módulo (upon the gallery's arrival in Lisbon), Gaëtan concluded the cycle of operations with a somber temple: in an antechamber, four similar ropes, made of rolled-up paper, hang along the walls, from ceiling to floor; in the back room, on an austere altar, rests another rope, "rotted by burial"1.

The foundation is ready, the theme is missing. Três Utopias Bárbaras, at Diferença (1980), was the third solo exhibition, and the ceremony continued. On the wall, Gaëtan draws (this time!) three analogous figures, with a monolithic aura, yet still predicting humanity within them. The charcoal lines overlap in thickness, speed, and fervor, and, familiar with the portraits about to emerge, we identify the elemental and instinctive qualities of that time. The audience was invited, through a text, to think, look, and act upon the pre-anthropomorphic figures, helping them to imprint the remaining breath. The following year, self-representation arrived.

These notes seem significant to me in explaining an artistic work often characterized as obsessive (and perhaps it was), which, however, emerged from an experimental, judicious, and diachronic foundation. While it is true that the artist's modesty guaranteed "a strong dose [...] of the unplanned" in his work2, the care with the titles of works and exhibitions, the devised mottos for sets of works, the categorical application of literary, film, music, and art history references, the rigorous thought in the assembly of each exhibition, are evidence of a diligent attention to the creative exercise. It is worth noting the fundamental precept of Gaëtan's drawing: being right-handed, he always chose to use his left hand.

Ricardo Valentim organizes and hosts at his home Anas, an exhibition of portraits of Ana Jotta by Gaëtan. There are numerous parallels and connections between the two, friends from the time they both briefly spent at ESBAL. The first entry on Jotta's exhibition list is Gaetana, Sala de Estar (EMI Gallery – Valentim de Carvalho, 1985), a presentation with Gaëtan and (Eduardo) F.M. In 1987, Gaëtan opens Une Chambre en Ville at Diferença, and in 2022, Ana opens Une Chambre en Ville at the Cité internationale des arts, Paris. In 2005, Gaëtan wrote an essay in the catalog of the retrospective Rua Ana Jotta (Serralves). And in 1982, Gaëtan drew and painted his friend, an encounter that comes shortly after his descent into self-representation and one of the notable detours of this journey.

There is a fondness for the domestic in Gaëtan: a large portion of his work is born from the mirror, but also from tables and trays, chairs and armchairs, roosters and squid for food. He turns from himself to furniture (Toucador, 1981/85), from furniture to drawings (O Carnaval dos Animais, 1986), from drawings to furniture (Plural Majesmático, 1981/85), and from drawings of furniture to himself (Gaitão, 1987), in a spiral circuit that reveals the comfort of someone secure in their place. What is at home, nearby, possesses availability, the same availability that so often led him to choose the most accessible model. This resourcefulness is still observed in the opening, playing and scheming (Vissi d'Arte, 1958/85, Nmkitpah, 1989). When he hires another model, this one is blind—Gaëtan avoids inspection of the sitter, whom he frames in fragments, faceless (Sermão a Jan Sanders, 1984), establishing the necessary command for the brief exit. Among all this, the closest point, in formal terms, to self-representation is when he draws Jotta.

Gaëtan stated several times that being the subject of his works was of no particular importance (so much so that he avoided the term "self-portrait"); the essence lay beyond that. Accepting that such a vast undertaking is more than an inventory of ego-dives, a nostalgic escape, or a tiring psychic investigation, the truth is that these "Anas" have a distinct stamp. The lines seem more considered, careful, yet also less resolute. When the artist depicts himself, it is difficult to read his face, always expressive but guarded, frank with a hint of irony, hypnotized by thoughts that fade away, searching for something with his gaze. In the drawings and paintings with Jotta, Ana rests or ponders, alienated, behind her hand, imperturbable, without a break in gravity or vibration. When Gaëtan draws himself with a frontal gaze, he observes himself/us; Jotta's frontal gaze observes only Gaëtan. From different results, what is added or highlighted to the complete oeuvre?

If, in following the litany of Gaëtans and Gaëtans, it seems easy to suggest a grasp of time, titles like Photomatou, A Última Morada e até La vue de Delft (which alludes to a fateful scene in Proust more than Vermeer) are peremptory in the consciousness of the brief, and yet the nearly transparent skeletons are hidden from view. In Anas, sincerity is more present.

The Anunciação stands alone. A diptych painted in acrylic tempera, majestic in size, inspired by the starting point of Jesus' narrative, recounting the long tradition. In Leonardo's version, the angel Gabriel is on the left and the Virgin Mary on the right. Here, we have Gaëtan on the left and Anna on the right, against monochromatic gray and orange backgrounds, respectively. They avoid each other, not with embarrassment, but with gentleness and fearlessness, in a particular silent council that both attracts and rejects, one that we lack the complicity to communicate.

Anas counts 14 Anas, to which is added a Gaëtan and two photographs, with another Ana and another Gaëtan portraying themselves, in the same frame. A project by Ricardo Valentim that renews the understanding of a body of work that seemed well-defined and, after all, Desenhado à faca3 persists in ingraining. The hand, blind and prudent, continuously and endlessly traced variations on a theme (remember that Gaëtan called the three series A Arte da Fuga), which is not exactly what we see. He captured and glimpsed passion and spirit, not in plain sight or at the core, but just beneath the surface, in a craft of control drawn from "improvisation"—the name of several of the Anas. It is an intimate work, an insistent silence against death, or the unused page.

Anas, by Gaëtan, is on display at Rua de São Vicente 19 (Lisbon) until September 6.

1Gaëtan: instalações [Material gráfico], 1977-1979, Biblioteca de Arte Gulbenkian

2 Interview with Gaëtan, by Raquel Santos, Entre Nós, 2005, RTP Arquivos

3Gaëtan, Quantum Satis, 1981 (colecção Ana Jotta)

BIOGRAPHY

Diogo ES Dietl, who holds a degree in History from Universidade Nova de Lisboa, has been following contemporary artistic creation since 2012, occasionally working on its edges through writing, consulting, promotion, production, and co-curating.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

29 Aug 2025

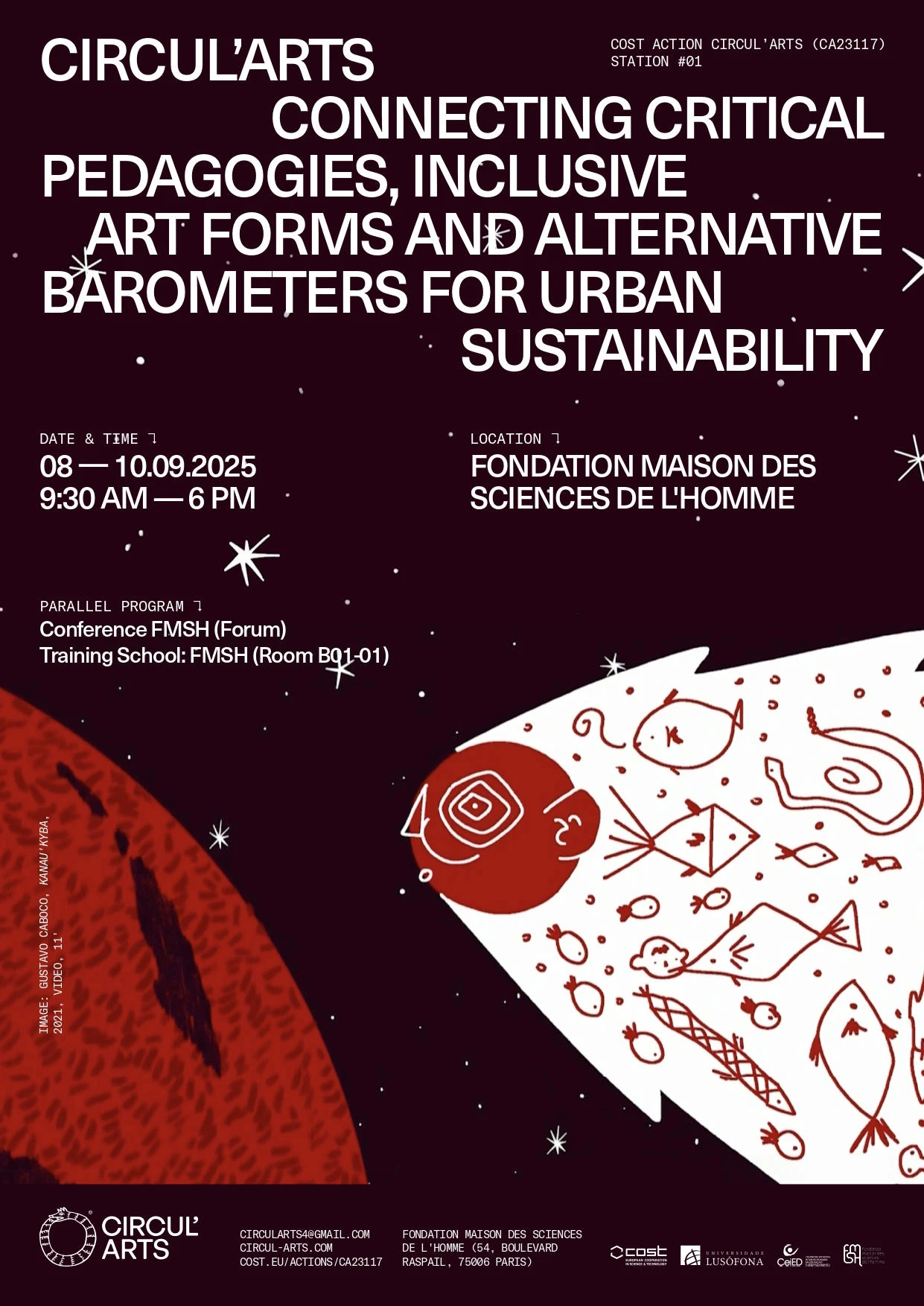

CIRCUL’ARTS: practices, critical and alternative barometers for urban sustainability

By Umbigo

Next

article

03 Sep 2025

About the Bienal de Arte Contemporânea da Maia 2025

By Mariana Machado

Related Posts