When I was in Belgium for the first time, in 2017, I spent ten days in Liège – an industrial city on the margins of the River Meuse – and just a couple of hours in Brussels: enough time to pass by the Manneken Pis, the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula and catch my flight home. This time, I travelled to Brussels for the 41st edition of Art Brussels, which took place in the Brussels Expo Hall from 24 to 27 April. I saw the city in the breaks from a packed press programme, through the art nouveau windows, but no more than in the conversations in the cafés, the exhibition texts, and the business cards I was busy collecting.

Nele Verhaeren – director of Art Brussels – made clear from the outset the main goal this year: to establish a close relationship with the city and its principal cultural institutions, affirming Brussels not only as a political centre, but also as a vibrant cultural and artistic capital. Perhaps that’s precisely why the press programme began with a visit to some of the city’s most important galleries and private art collections.

We left the historic centre to head to lxelles, a commune known for its students, artists and intellectuals, with dozens of galleries just a few steps away. Among them, the QG Gallery stood out with the exhibition High End and Above by Frank Gerritz, where the deconstructed canvases strain the limits of the pictorial surface and, ultimately, the fine line between painting and sculpture. I then remember the Xavier Hufkens gallery, which, at the time I am writing, is hosting the exhibitions Mysterious Leap, by Matt Connors, and And there is a place you will not be able to return, by Nathanaëlle Herbelin. The outcome” of research into the mechanisms of translation between observation and representation, Mysterious Leap presents a series of small and large-scale paintings. These works bring together the colours, shapes and textures that are a constant of the artist’s visual universe; fragmented compositions that – although visually distinct – dialogue with each other, engaging in a game of repeated contagion. In And there is a place you will not be able to return, Matt Connors’ abstraction gives way to Nathanaëlle Herbelin’s raw and melancholic figuration. Through a series of portraits and paintings of interiors shrouded in atmosphere, the artist recounts moments of intimacy and rituals that, in the Jewish religion, mark the process of mourning. As I write, Dinner with Hard-Boiled Eggs comes to mind, a representation of Se’udat Havra’ah, the “meal of condolence” that follows a funeral. I recall the vigorous brushstrokes, the almost grotesque figures and the hard-boiled eggs on the table – a symbol of the cycle of life and renewal. At the same time, I reflect on the intimacy of sharing a meal and the small gestures of collective resistance. Here, individual history appears inseparable from collective history, dogged by violence, political tension and a deep sense of uncertainty.

This sense of political disquiet seem to loom heavily over the city’s art scene. I sensed it again at BOZAR – Centre for Visual Arts, with the exhibitions Familiar Strangers – The Eastern Europeans from a Polish Perspective and Khorós, by Berlinde De Bruyckere, and later at Art Brussels. After all, if on the one hand, fairs are a space for the market to go through its motions, on the other they are also a meeting place where critical thinking – through art – can gain greater traction.

In 2025, more than twenty thousand visitors passed through Art Brussels. At the top of Heysel Park, 165 galleries from 35 different countries gathered, more than 30 percent of them returning from previous fairs. The usual established names were joined by emerging artists and galleries and a series of projects with a strong curatorial focus. As a highlight I would pick the inauguration of The Screen programme; where six galleries presented a video by one of their artists, underlining the significance of time-based media in contemporary art; and Céline Condorelli’s project, a site-specific installation that aims to reimagine the entrance to the fair. Represented by Galeria Vera Cortês, the artist installed a structure similar to a theatre curtain, suggesting that when we enter Art Brussels, we are already stepping onto a kind of stage set.

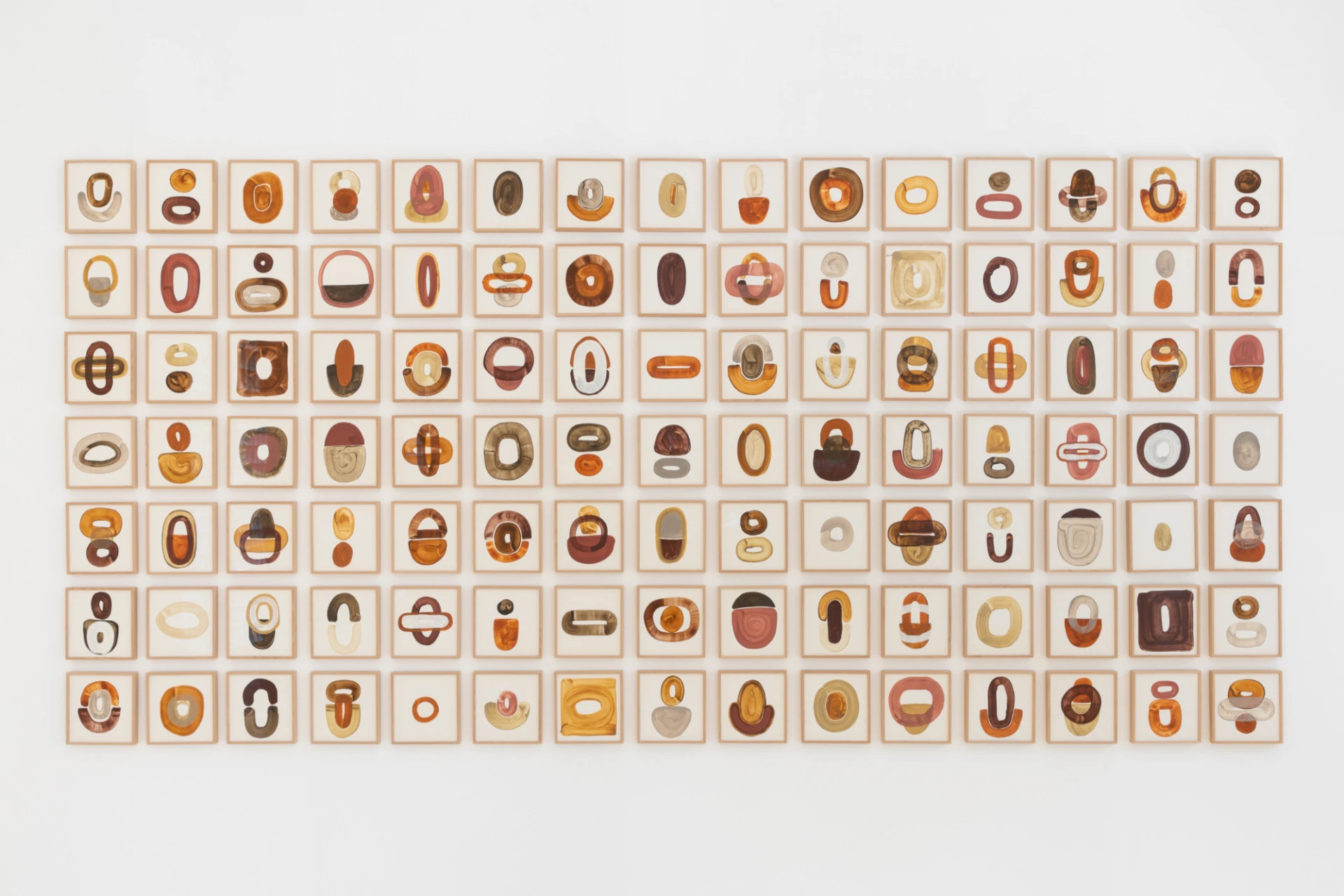

Like a theatre production, the fair stages and produces a narrative about contemporary artistic production. For two days, I wandered through its halls. They were white, almost sterile, and contrasted with the concrete surfaces and exposed steel beams of the Brussels Expo Hall. The overwhelming scale of the space led me to ask: How can I write about this enormous piece of theatre? I turn to the book that kept me company on the plane to Brussels: Techniques of the Observer, by Jonathan Crary – a must-read I had somehow kept putting off until now. The author introduces the fourth chapter of the book with a reflection on retinal after-images, an optical phenomenon that describes the presence of sensation in the absence of a stimulus. I inadvertently appropriate this idea and apply it to the exercise of writing. After my visit to Art Brussels, I sit in a café near Avenue Louise and close my eyes, as if recovering from a kind of visual overdose. And then I write down some of the images flashing before me that flare up with the same intensity with which they later fade away:

*

(1) The mutant bodies of Salomé Chatriot, represented by the Berlin gallery OFFICE IMPART. The artist’s breathing and heartbeat are fed into a database, later transformed into this electronic sculpture. I see a speculative anatomy, where the eroticism of flesh is intertwined with the metallic sheen of steel. Body-machine. Machine-body. An unsettling reconciliation between the intimate and the artificial, the organic and the digital, between the human body and whatever – who knows – we will become.

(2) Kafka’s boat (1990), by Wolf Vostell, on the EAST gallery stand: a Second World War military boat, with a few bodies piled up and, among them, a small television set. This work – as sensitive as it is brutal – is a reference to the first military conflict captured on our TV screens. Since then, violence has become commonplace and death a condiment to spice up our mealtimes. Kafka’s boat is not a recent work, but it seems to reflect contemporary times. Next to it is Jesus with a TV heart (1995), which drives a wedge between sacred iconography. Jesus’ heart has been replaced by a screen whose image is distorted by static interference. An empty space remains behind in his chest cavity. Is love of one’s neighbour already mediated by our screens, conditioned by a need to be seen? Could it be that Jesus too – symbol of Christian religion – watches violence flicker on the screen, sometimes powerless to act, and at other times deeply blasé?

(3) I WISH I HAD A TIME MACHINE – words that occupy the physical space of the exhibition Time is not a line, by Karo Kuchar, for SUPPAN gallery. They swirl before me in disorderly fashion, forming new constellations and dissolving like dream matter. HAD – MACHINE – TIME – I – WISH / MACHINE – WISH – I – HAD – TIME. Interested in deconstructing the linearity of time, the artist offers up a dreamlike universe where we can finally escape the present that imprisons us. Her pieces, created in fabric and then stuffed to give them more volume, are doorways to another temporal dimension. They are reminiscent of clouds or cushions – after all, the suspension of time would appear to rely on both flight and sleep. I then imagine a body that leaps into the void, throws itself over the portal and disappears. They’d already be on the other side by now. Maybe they will be sending a smoke signal, or a fax to their old office. On this side, the words echo once more. We read: THIS TIME, I FOUND A TIME MACHINE.

*

These are brief, fleeting impressions – a summing up of my short stay in Brussels: enough to conclude that I will have to be back again, soon enough.

Umbigo travelled to Brussels at the invitation of Art Brussels.