article

Finally Home, Lastly Conversation | Espaço Coleção Arte Contemporânea – Lisboa Cultura

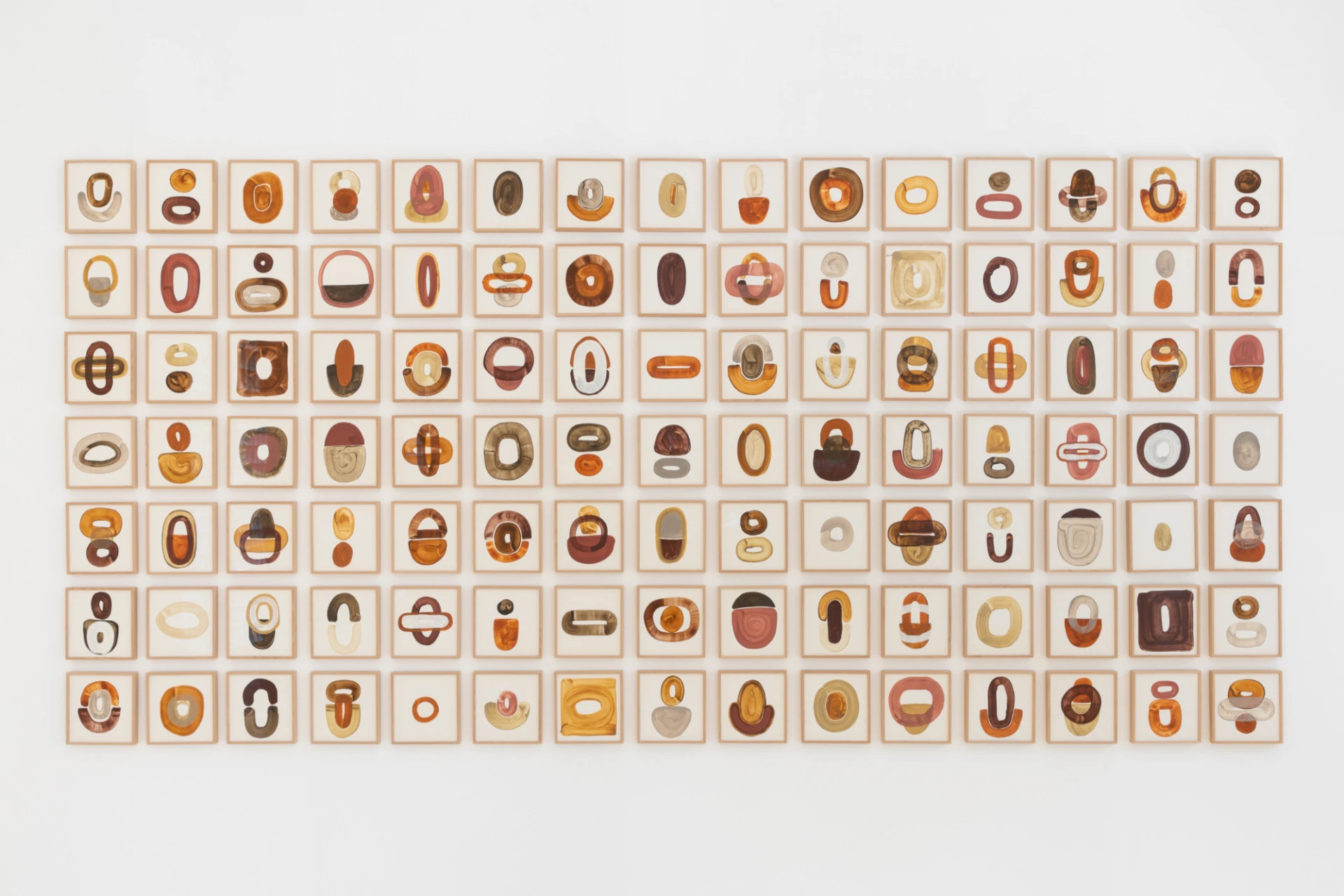

I am writing to you about the first exhibition that presents and articulates part of the collection, composed primarily of some of the acquisitions made throughout 2024, along with some previous ones, drawn by complicity and parenthood. What stands out in the composition of this exhibition are dialogues of "aesthetic affinities and spatial relationships," say Sara Antónia Matos and Pedro Faro, curators of this first exhibition. But that's not all. There are very evident kinship discourses that show us that we are, in fact, at home.

Upon entering a familiar space, we immediately recognize who greets us at the door. It's Fernanda Fragateiro greeting us (not in person) with her clear and concise vocabulary, which quickly disarms us of any timid ceremony—the kind we feel in the first moments of intimate gatherings. We were just finishing greeting Fragateiro in the entrance hall, where we exchanged a cordial conversation before heading to the living room to greet the rest of the guests, when we were stopped by Luísa Cunha. She's in a hurry, as she always follows her own schedule, and often arrives late. So much so that she often lingers at the door. Well, Fragateiro was briefly talking to us about an old work, along with a theme dear to her heart, where she advocates demolition as deconstruction, opposing the notion of destruction, when we hear Luísa Cunha arrive. I hear, behind my shoulder, an attentive voice asking permission to enter, so that it can see what Fragateiro was saying, as if interrupting without meaning to interrupt.

What I'm trying to convey is the peculiar feeling of familial hospitality we feel upon entering a space that brings all these voices, our neighbors, into dialogue. But which voices? What space? Who, where? That is the question, the title of the exhibition, immediately answered by the curatorial proposition of the house that now houses the municipal collection. Evidently, the voices that make up the Lisbon City Council's Contemporary Art Collection cannot all be represented in unison, in the same score, on the same page of the Lisboa Cultura space. The space itself doesn't allow this either, and thankfully so. Rather than maintaining a permanent exhibition, this space cultivates encounters and confrontations through temporary exhibitions—establishing intermittent discourses that reject the fixity of inherent correlations and interpretations. This collection, beyond the plurality of works, is continually under construction. Although the who is a variable, the where is a constant, at least for now, and we can define it in good terms. What was once one of the Municipal Galleries, on Avenida da Índia, is now the Espaço Coleção Arte Contemporânea – Lisboa Cultura. Once again, I insist on the narrative of a place that was already familiar to us.

I am writing to you about the first exhibition that presents and articulates part of the collection, composed primarily of some of the acquisitions made throughout 2024, along with some previous ones, drawn by complicity and parenthood. What stands out in the composition of this exhibition are dialogues of "aesthetic affinities and spatial relationships," say Sara Antónia Matos and Pedro Faro, curators of this first exhibition. But that's not all. There are very evident kinship discourses that show us that we are, in fact, at home. Still, I hope it becomes clear that the inheritance and parenthood I here declare are not marked by a shared nationality, but by the familial nature of the narratives that characterized our society—Portuguese and Lisbon—: passing through colonialism, with the criticism of Délio Jasse, which we already saw last year at the Pavilhão Branco in the Galerias Municipais; by postcolonialism, with the work of Ângela Ferreira, who has accompanied us over the last decade; by the emigration of another generation, with the photographs and accounts of Vasco Araújo—named after the exhibition's title—; as well as by Filipa César's short film, which makes us reflect on the constitution and duration of a revolutionary, violent, slow, and solitary process and project, contrary to what history and literary imagination tell us. And yet, using this same analogy to home and familiarity, it would be impossible not to mention the artist who is, in fact, enveloped in this intimate representation. I refer to Patrícia Garrido, who presents the idea of home as an extension or integral part of a body—her own—through which she explores how memory, identity, affections, and even reality are shaped by the environments we occupy. Yet, the instability of his sculptures, as well as the political instability, tells us that this is a process in constant flux, negotiation, and transformation. I am writing about what we call dwelling, both the body and the house. Ultimately, I hope the mayors paid attention when they opened this space and exhibition.

Well, we find all these narratives gathered around what we consider the memory of (our?) nation-state. And that's also why we feel at home in this exhibition and, eventually, in this collection. There's no curated discourse imposed on how we'd like our city or nationality to be perceived. There's only reality, told by a plurality of identities that, evidently, also use their imagination and subjectivity to reflect on what makes up our history and society. In other words, what I mentioned in a previous text about Basel Art Week doesn't happen, where we didn't recognize the world represented there, but rather an alienated perspective.

But our national narratives are not made solely of social struggles and colonial memories. There is a certain dystopian spectrality, a certain utopian ruin, also very present, both in this exhibition and in what we consider the future of this generation. We recognize another variety of artists who, intentionally or not, confirm this perception. From Igor Jesus, with the distortion of faces enlarged and deformed by the very means by which they are captured; to Jorge Queiroz and Manuel Rosa, who represent sanitized skulls separated from the whole to which they were associated; to André Cepeda with the trail of the accumulation of time in the Anthropocene, solitary and melancholic; to Paulo Nozolino with the decay of waiting and hope; to Isabel Cordovil with the provocation of an agonizing decision; to Marta Soares with the representation of the degradation of urbanization; Rui Chafes with what looks like a hunting trap, instead of what could be a mask; and Ana Jotta with two sculptures nicknamed “patas,” (paws) which recall the bodies in Pompeii, charred by the volcanic eruption.

After everything I've written, I believe readers understand the feeling of familiarity I've regularly evoked throughout this text. Familiarity with critical discourses, mourning, names, and space, but also with a curation that begins in the home and ends in the coffin. That is, one that recognizes the duty and responsibility of a museology and a collection that allows for "generational, geographic, and cultural divergences," fostering public debate "when the global world seems precarious—or even regressing—regarding freedom and civil and human rights," the curators conclude in the exhibition leaflet, emphasizing that they consider public accessibility of the municipal collection essential. Well, here we have it, the collection, at least in part.

Who? Obviously, it was not possible to mention all the names present in this first exhibition about the contemporary nature of this art collection – it is up to the reader to fulfill their quota and discover those who were left out.

Where? At home. In a house. At last. Where relationships deepen and conversations change us.

WHO WHERE / QUEM ONDE is on display until September 7, 2025, at the new Espaço Coleção Arte Contemporânea – Lisboa Cultura.

BIOGRAPHY

Benedita Salema Roby (b. Lisbon) has a degree in Art History (2019) and a master's degree in Aesthetics and Artistic Studies (2022) from the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities of Universidade Nova de Lisboa with the dissertation ‘Graffiti: Considerations on the Aesthetics of Transgression in the Public Space of the City’. She is currently doing her PhD in Artistic Studies - Art and Mediations at the same institution, where she is developing a research, with funding from the FCT, centred on the potential for societal and collective liberation around transgressive (artistic) practices such as graffiti and political graffiti. On this theme, she also participates in the making of documentaries and organises workshops on practice and thought for young people. Her thesis project, entitled ‘The Deconstruction of the (Experience of the) City and the Construction of the Counter-Public Sphere: Transgressive Creative Writing, Aesthetics and Politics’, is supervised by Cristina Pratas Cruzeiro and Joana Cunha Leal. As well as academic publications, he writes about emerging artists and visual and performing arts exhibitions for independent magazines such as Umbigo and Sem Título.

ADVERTISING

Previous

interview

20 Aug 2025

Interview with Marta Castelo, author of Umbigo´s monthly cover

By Maria Inês Mendes

Next

agenda

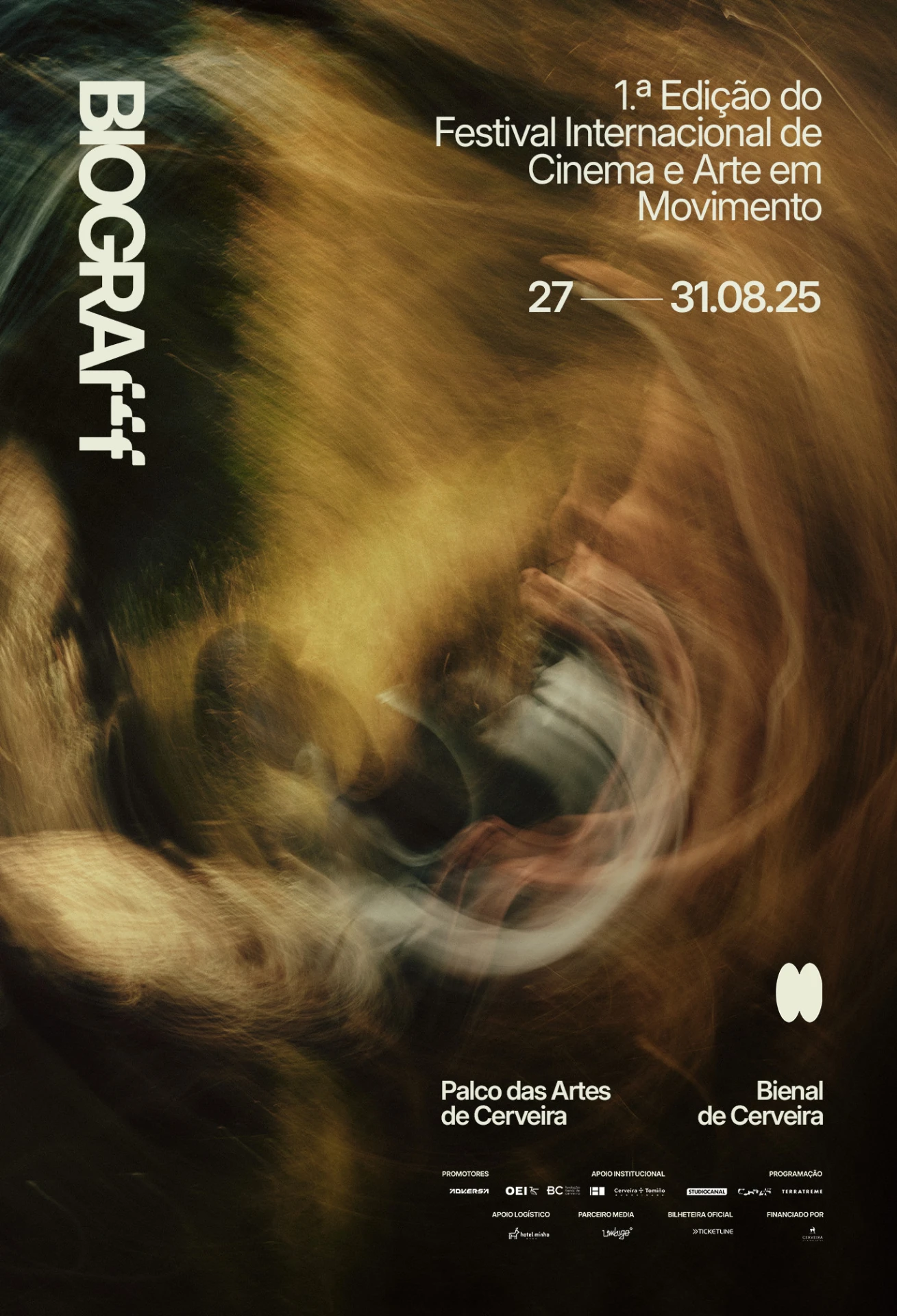

22 Aug 2025

BIOGRAF - International Film and Moving Arts Festival kicks off on 27 August in Vila Nova de Cerveira

By Umbigo

Related Posts