article

Improvisation in 10 Days by Tarek Atoui: Polyphonic encounters as sonic resistance

In his book "Sonic Agency" (2018), Brandon LaBelle describes sound as a political and relational force, able to cross physical and geographic boundaries and engaging bodies and spaces in radical, deeply sensorial ways.

LaBelle’s words came into my mind while I was wandering through Tarek Atoui’s unique solo exhibition at Hangar Bicocca in Milan, the first in Italy. Atoui (1980, Beirut) is an artist who has turned listening into a collective act as well as an artistic practice and who defines himself as a “nomadic being,” seeing sound as a space for encounter and exchange.

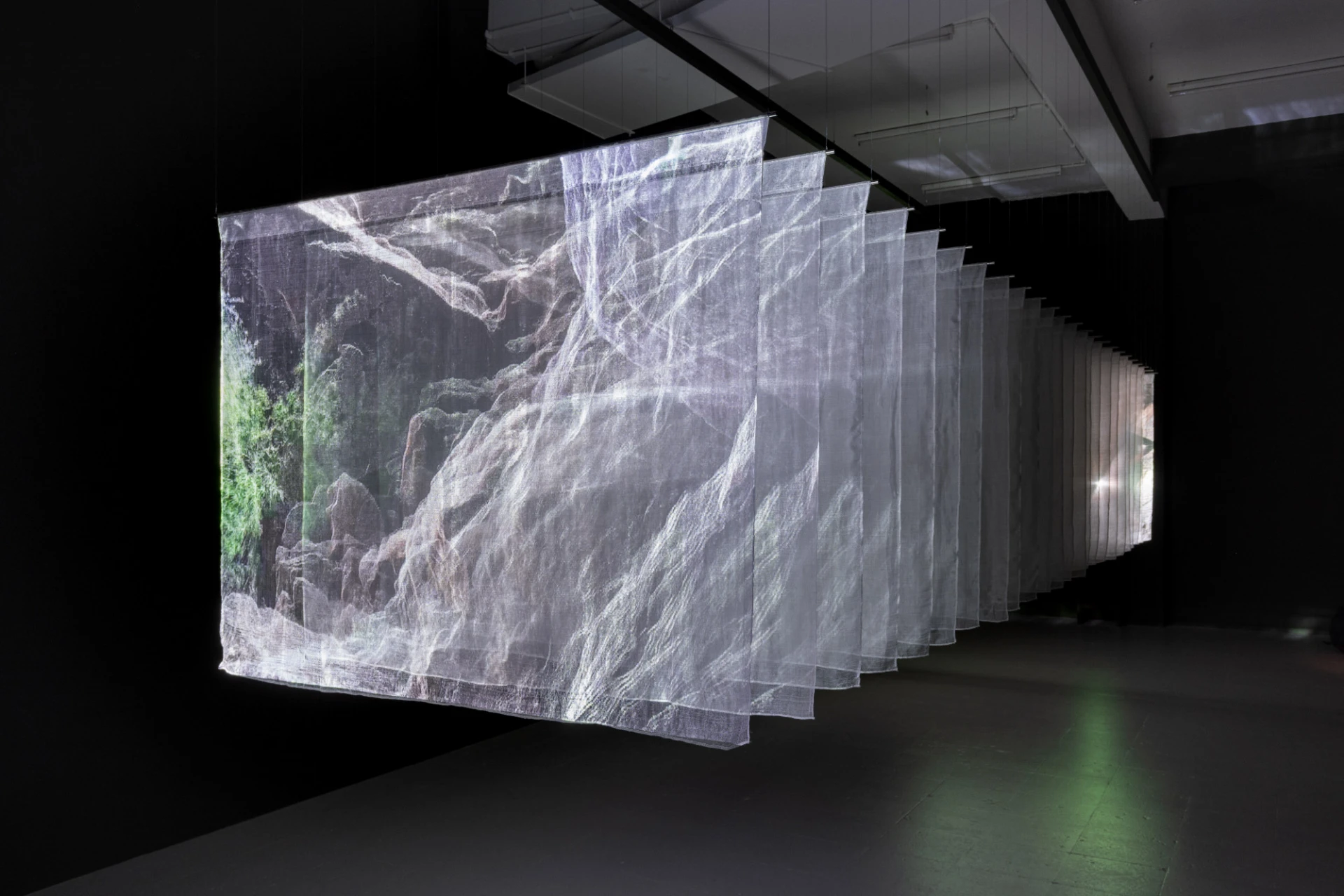

Improvisation in 10 Days radically transforms the identity of the exhibition space, turning it into a living organism that breathes, pulses, and resonates. The title refers to the show’s early phase: ten days of on-site improvisation and composition that generated the core of the exhibition. The resulting sounds continue to resonate through the gallery, activated by a network of algorithms that Atoui calls master brains, triggering the instruments without the need for human performers.

The exhibition is an evolving organism, made up of works adapted and reinterpreted for the vast industrial spaces of the Shed. One of the core body of work is Souffle Continu, powered by airflows generated by engines and controlled by computers. The name references circular breathing, a technique used by wind instrument players to produce a continuous stream of sound. This group of works emerged through collaborations with deaf students, as Atoui sought to explore sound through physical, embodied experience. In the works from this group, Wind House #1 and #2 (2023-2024), vibrations of sound waves propagate through space and are felt both sonically and physically by the audience.

Another group of works, The Rain (2023-2024), was developed during a residency in South Korea, where Atoui collaborated with traditional musical instrument craftsmen. The resulting pieces are exquisitely customised from refined materials, such as as ceramic, porcelain, hanji paper, and metal, inspired by the four natural elements. Interestingly, the intellectual property of the instruments remains with their maker, while Atoui considers the sound composition and the activation system to be his true artwork. It is a subtle reflection on authorship and the role of the artist as someone who is not a solitary creator but as a facilitator and orchestrator, but mostly someone who must collaborate.

Perhaps the most poetic moment of the exhibition is Water’s Witness (2020-2023), a project based on field recordings and studies carried out in port cities around the world. Once central to daily life, many of these harbours have become sealed-off, inaccessible security zones. Sitting on massive stone blocks, which are, in fact, sound sculptures, I listened to vibrations and sonic traces that seem to return those places to us. Here, sound becomes a sensitive archive, a fluid memory of what once was and what might be again, but also an archive of sounds and past echoes tied to these places.

Atoui’s exhibition invites us to listen differently, with the body, with the skin, with empathy and memory: to cross sound the way one crosses borders or coastal cities. I recall how John Cage rejected the centrality of the composer; similarly, Atoui dissolves authorship by involving diverse communities in a process of collective creation. In his open-ended, layered approach to composition, we can perhaps feel the influence of Atoui’s Arab heritage, not only in the notion of collaboration and hospitality typical of Mediterranean cultures but also in the modal and polyphonic structures of Arabic music which creates spaces where multiple voices coexist without hierarchy. He opens up passageways, restoring sound’s political, collective, and accessible power and, more importantly, he invites us to do the same.

BIOGRAPHY

Orsola Vannocci Bonsi is a cultural producer and advisor who has called Lisbon home for eight years. Through her work, she fosters connections through her research and the projects she helps bring to life. With experience as a sales director and gallery manager in various Portuguese art galleries, she was also project manager and artistic director of FEA Lisboa, founded the curatorial collective Da Luz Collective, and contributed to the programming of festivals in Italy and Portugal.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

18 Jun 2025

‘Somos Todos Capitães’

By Mariana Machado

Next

article

23 Jun 2025

By Laurinda Branquinho

Related Posts

[A] Alexandra Bircken, [L] Culturgest-lehev.jpeg)

©photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio-7yoip.jpg)