article

Sex and Solitude by Tracey Emin: Radical Womanhood and Shared Viscerality

The brutal yet tender shared reality of Tracey Emin, made of continuous oxymoronic contradictions, is a beacon that illuminates a common experience of female resistance and necessary sisterhood.

In 1963, Annie Ernaux decided to do something that at the time in France was illegal, dangerous, but mostly stigmatized: she chose to end an unwanted pregnancy. Her experience was marked by solitude and silence, which she would share years later in her memoir L’Événement (2000). Walking through the rooms of Palazzo Strozzi, where the exhibition Sex and Solitude by Tracey Emin is currently on view, I sensed something of that same visceral feeling: an exquisitely feminine pain that becomes body, memory, art. A shared suffering that turns into sisterhood, motherhood, identity.

The exhibition traces the British artist’s entire career, from the 1990s to 2024. One of the first works on display, on the main floor of the Palazzo, is Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (1996), shown in Italy for the first time. In 1996, Emin locked herself naked for three weeks in a temporary studio built inside a gallery in Stockholm, working and attempting to reconcile with painting, a medium she could no longer physically endure after two abortions. Visitors could observe her through small fisheye lenses on the walls. The entire installation - paintings, objects, furniture - was preserved intact and is now presented in its original form in Florence.

Like Ernaux, Emin experienced abortion at a moment of profound vulnerability: young, alone, at the beginning of her career. Like Ernaux, she faced a doctor who didn’t want her to go through with it. The choice that she made, and the trauma surrounding it, became a central part of her artistic language. Emin has often mentioned that one of the reasons she continues to speak so openly about abortion, and broadly violence experienced mostly by women, is precisely because so many don’t. And that silence, she says, weighs on her.

Tracey Emin has never stopped portraying the body. A body violated, ill, resilient. Rape, cancer, abortion: each of these tragic experiences, which she has lived through, enters her work with both brutality and tenderness. At Palazzo Strozzi, we encounter paintings, sculptures, neon works, and textiles, some created especially for the exhibition, that share all the same carnal urgency, the same emotional intensity. The bodies in her paintings merge in abstraction and are charged with desire, but also with pain. Her sexuality is never sanitized: it is always tragically true, inseparable from suffering.

For this almost violent honesty, Emin says she has often been seen as a “witch”, a “banshee”, accused of creating a sort of pornography of pain. Yet her art is, on the contrary, a radical space of truth. In her practice, pain and love, suffering and vitality coexist and collapse into each other. The name of the show—and the large pink neon on the façade of Palazzo Strozzi—Sex and Solitude, is a combination that defines not only her work, but the very existence of many women: the ongoing tension between the desire for connection and the inevitable isolation of existence.

The brutal yet tender shared reality of Tracey Emin, made of continuous oxymoronic contradictions, is a beacon that illuminates a common experience of female resistance and necessary sisterhood. As Annie Ernaux highlights in her book, when describing her profoundly feminine experience:

“It’s possible that a story like this will cause irritation or repulsion, that it will be dismissed as being in poor taste. But having lived through something—anything at all—grants you the inalienable right to write about it. There are no inferior truths. And if I didn’t go all the way in telling this story, I would be contributing to the silencing of women’s realities, taking the side of the male domination of the world.”

The exhibition is on view at Palazzo Strozzi until July 20.

BIOGRAPHY

Orsola Vannocci Bonsi is a cultural producer and advisor who has called Lisbon home for eight years. Through her work, she fosters connections through her research and the projects she helps bring to life. With experience as a sales director and gallery manager in various Portuguese art galleries, she was also project manager and artistic director of FEA Lisboa, founded the curatorial collective Da Luz Collective, and contributed to the programming of festivals in Italy and Portugal.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

02 Jul 2025

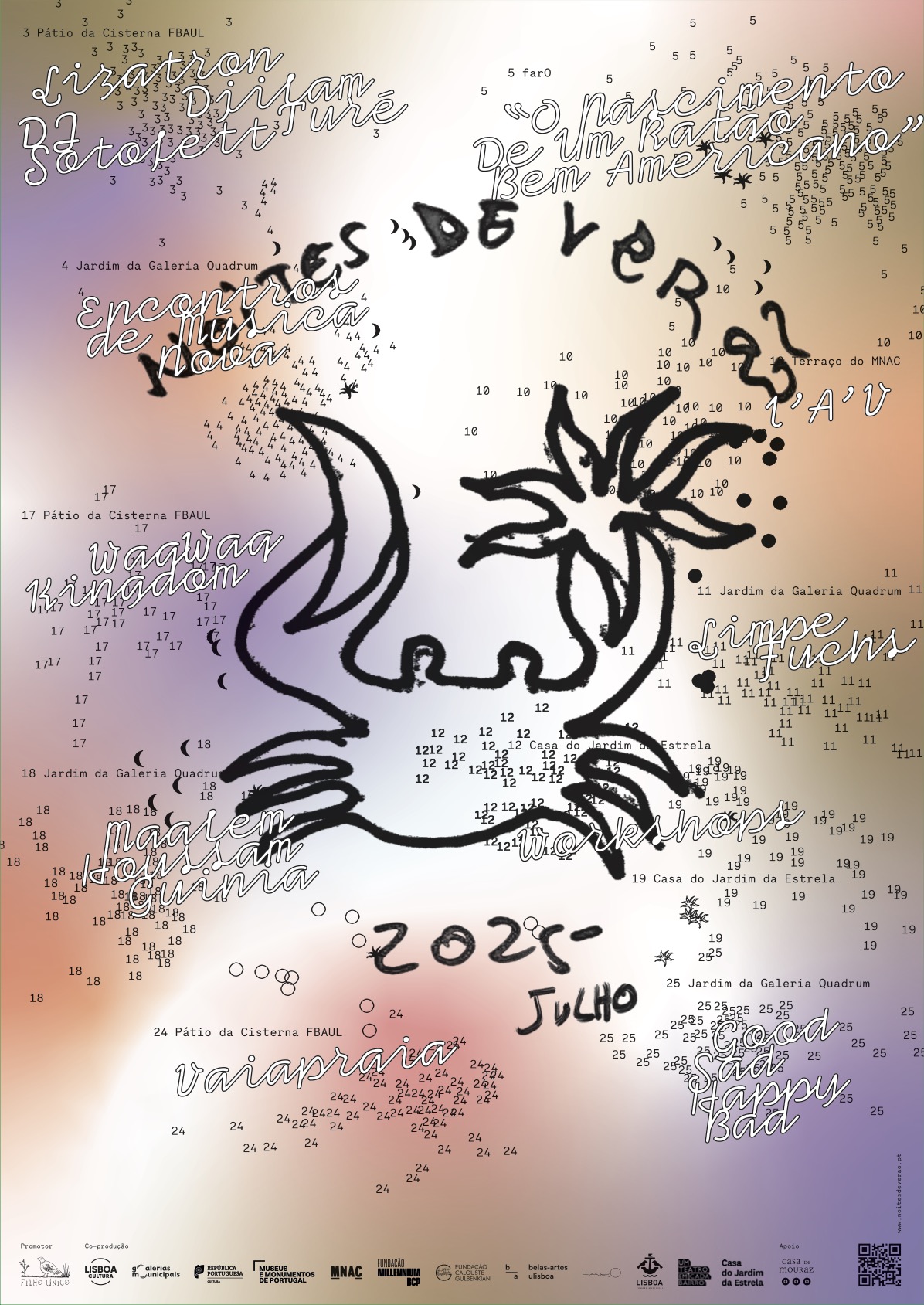

Noites de Verão 2025 kicks off on 3 July in Lisbon

By Umbigo

Next

column

07 Jul 2025

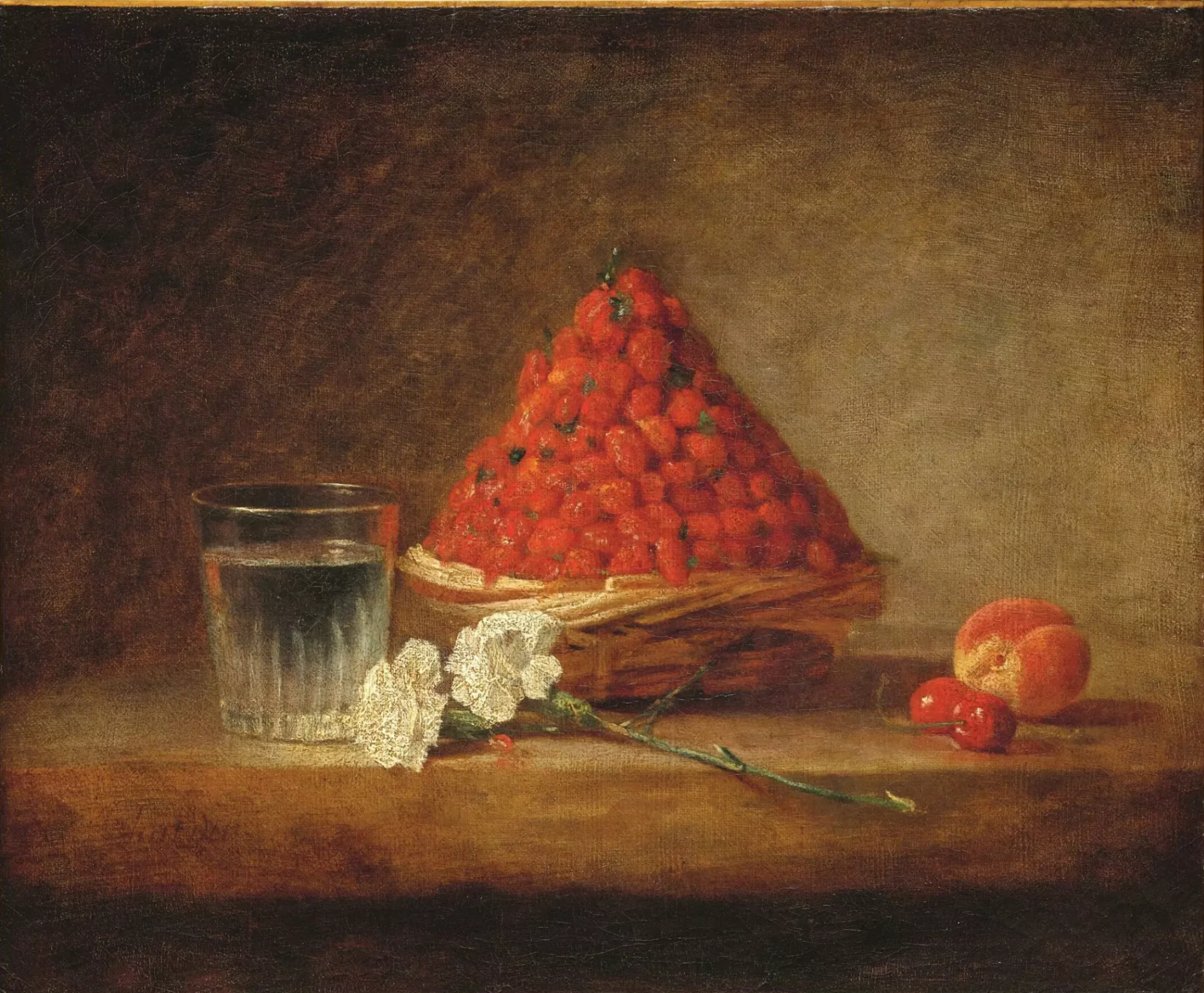

Mixed media on paper #10 - The strawberries of the saison

By Luísa Salvador

Related Posts

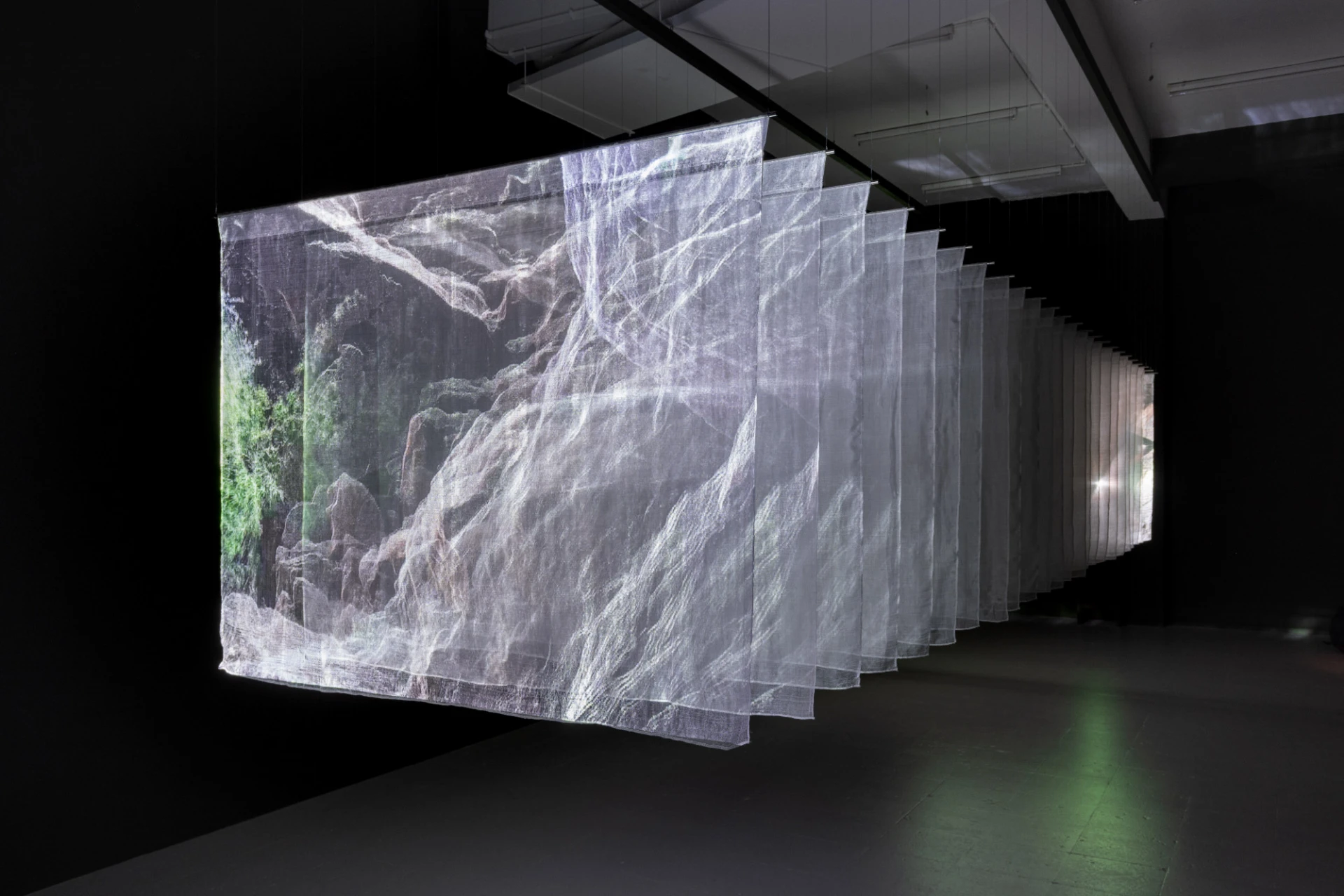

[A] Alexandra Bircken, [L] Culturgest-lehev.jpeg)

©photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio-7yoip.jpg)