Without ignoring my inattention or inexperience as a factor, I cannot remember ever having heard the term ‘tribute’ applied to an art exhibition consisting of pieces by the subject himself. It immediately brought me back to the ‘music’ field: cover bands, faux rock stars, amateur musicians living and feeding off the successes of other people in fringe nightclubs on the outskirts of cities, attended by bikers and other punk notables whose aesthetic and stereotype are somewhat similar to the figure of Lawrence Weiner.

Avoiding the characters’ outward appearances as the only proof of the resemblance, perhaps this reasoning is not quite as nonsensical as one could assume. In one of the artist’s legendary statements – found in that compiled corpus of texts known as Art In Theory 1900-2000 -, he tells us: ‘Anyone who makes a reproduction of my work is creating art that is just as valid as that made by me’[1]. This freewheeling translation ‘from one language to another’ – profoundly marked by the conceptual language of late 60s – could certainly be included in an old-fashioned discussion in today’s art – except in the field of painting – about the gesture itself. This sentence remains relevant, however, because it was not only insignificant to the artist whether the piece was made by him or not, it was also inconsequential to him whether it was built at all or whether it was just language.

To use the same metaphor, Weiner is not an interpreter of his own work – even if he could be – but rather a composer who passes on the musical score and is not held accountable for what is done with it once it is accepted, or else ambiguity – which allows for subjective interpretations – would not be among the most widely discussed topics in the American artist’s oeuvre, and one that provides the motto for the title of this exhibition. He uses the term mise-en-scènes to define his practice, and says: ‘Art that imposes conditions – human or otherwise – on the audience for its appreciation is, in my eyes, aesthetic fascism.”[2]

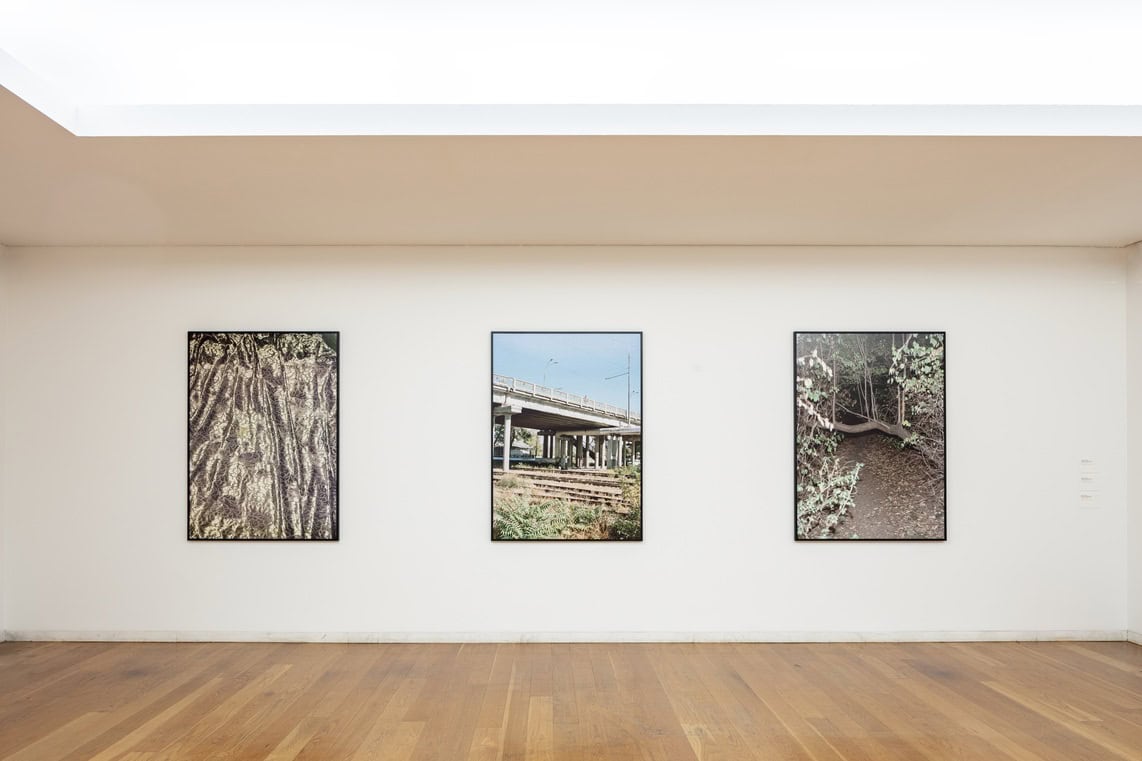

But what is this gestural sensuality that the curators of this tribute speak of? The answer – slightly at odds with the dismissal of the material previously defended – can be found in the same statement that validates this artist’s practice as sculpture, something which he claimed in the first place. In a 1997 interview with Benjamin Buchloh, when questioned about the reason for this designation, Weiner replies: ‘I understood then that I was working with the same materials that people who are called sculptors use. I dealt with clay, I worked with all the removal and gluing processes. It is a problem of labelling. I also came to appreciate that I was dealing with very broad structures in an highly formalised way (…) I don’t believe I was doing anything much different from someone who handles 14 tonnes of steel’[3]. From language, equipped with ‘a total literalness and metaphorical drive’[4], the artist achieves materiality through a ‘realistic and performative relationship with the viewer’. In the different materials we can see in this exhibition – books, posters, magazines, records, as well as the usual wall sculptures -, we understand how language, as a material, is related and adapted to its support; how it deals with the mass, the surroundings and its context. I say ‘we understand’ because these relationships are individually created from the audience’s seat, and for the artist these relationships are sensual and performative, much like a dance.

From a personal standpoint, the piece that best fulfils the purpose of a tribute is perhaps A REMOVAL FROM THE LATHING OR SUPPORT WALL OF PLASTER OR WALLBOARD FROM A WALL, inextricably bound up with the photo of Weiner bare-chested, with his usual long beard and a cigarette in his mouth, ‘drilling’ the walls of Bern’s Kunsthalle himself, in that crazy affair called When Attitudes Become Form. If one applies the same exercise to the title of the exhibition – I’ve Always Loved Jezebel -, the same exercise that would be applied to any of the artist’s other works, I could say that it leads us to a sense of nostalgia, referring to the ethics, integrity and attitude to which the consistency of the artist’s work has made us familiar. This is my interpretation, but in these terms – Lawrence Weiner’s -, it is valid and it does exist.

I’ve Always Loved Jezebel is at Galeria Cristina Guerra in Lisbon until November 9, 2024. It is jointly staged by Thiago Tannous, Pontogor and Joaquim Pedro in partnership with the Moraes Barbosa collection.

[1] Harrison, C.; Wood, P. (2003). Art In Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Blackwell Publishing, p. 893.

[2] Idem, p. 894.

[3] Translated from the book by Delfim Sardo entitled O Exercício experimental de Liberdade, from the interview with the artist called “Art is not about Skill”: Benjamin Buchloh Interviews Lawrence Weiner On His Sensual Approach to Conceptual Art. Available in: https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/art-is-not-about-skill-benjamin-buchloh-interviews-lawrence-weiner-on-his-sensual-approach-to-54588

[4] Sardo, Delfim. (2017). O Exercício Experimental de Liberdade. Orfeu Negro, p. 28.