article

On the road: Porta 33, Village School, Francisco Janes, and Chain Reaction

Food is more satisfying when it is shared and accompanied by conversation. It is not in vain that one of the great treatises of Western philosophy, The Banquet of Plato, has food as the center of classical orality and of a labyrinthine debate on the table, watered with the fire of Dionysian wine, but seasoned with Apollonian judgment.

The food is comforting, the drink is liberating, and the presence of many guests ensures the delight of sharing and dialogue. Introverts let loose, extroverts hold back; cross-talk; secrets confided amid lustful laughter; new friendships, old friendships; memories rekindled in the heat of nostalgia. It is a ritual, as superficial as the dictates of good manners, as deep as the debate over the foundations of States.

We sit at the table and let the magic of food do its ancestral, social, and biological work, which was natural for the ancients and that modern people have learned to forget. We change plates, pass the food between our hands, keep the glasses full, and over time, when the food disappears and the crumbs scatter on the floor, we eat from each other. Life happens.

If we want to keep a cohesive community, nothing is better than this ritual. If we want to overthrow a regime, there is nothing better than the heresy of a group meal.

It is surprising that food, so routine, so elemental, remains the most radical force that civilizations have ever known. Maybe because meals at the table have lost the unifying quality of yesteryear. Perhaps because nothing new and similar has replaced it as social glue or cement. Perhaps also because what is proven and confirmed has to be, from time to time and paradoxically, equally renewed, recalling the past logics that structure communities: sharing, empathy, and generosity.

From these memories, we keep impressions, fleeting brushstrokes of an intense and pleasurable encounter.

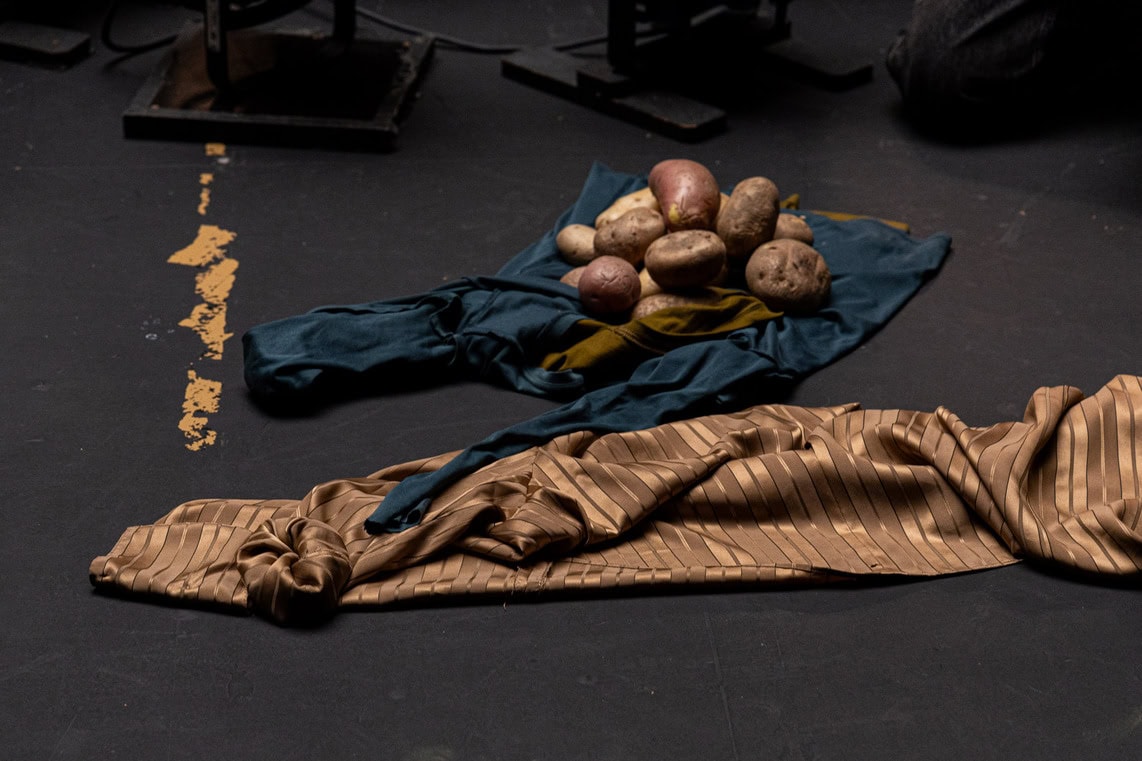

The meeting point was PORTA33. The occasion is the Chain Reaction project by Elizabeth Prentis and Hugo Brazão, whose aim is to establish bridges of dialogue between artists, curators, and institutions during the many scheduled meals, gathering in an “assembly of abundance” – a project by Jesse James and Walk&Talk – optimistic thinking and future perspectives. The purpose is contained and inscribed within a critical and institutional discourse, but the scope is much greater: the construction or consolidation of a community.

More than twenty people sat around the table, exchanging experiences about the regional and national art system, showing what they have been developing over the last few months. The logistical nightmare was compensated for by the satisfaction of the diners and a good mood.

Earlier, in the PORTA33 exhibition rooms, Francisco Janes showed the result of a residency at Escola da Vila, in Porto Santo – an extra-peripheral territory, limited in every way by geography. The exhibition is based on the same working core as Chain Reaction: the local community.

Videos, photographs, and sounds serve as references for the construction of a place that, for the moment, seems to exist on the uncertain edges of a dream. The editing of the videos follows the evocative structure of a poetic and oneiric essay, and the montage leads to an immersion in the film excerpts that Janes strung together during his long residency at Escola da Vila. There is an immediate elementality: the wind, the moon, and sunlight. The videos have something peripatetic, wandering about them; a reverie by the seashore, the dragon trees, and geological phenomena of Porto Santo; a meditation mediated by the camera lens, contemplating the effects of time on living things.

The sound accompanies the video and then fades into darkness. The natural and human landscape is also a soundscape. In the absence of an image, the sound serves as a reference for the imagination, pushing the viewer to complete the multimedia and phenomenological composition designed by Janes.

At once a cultural and community space, the school was rescued from oblivion and dignified by PORTA33. If it weren’t for the goodwill and energy of its founders, Cecília and Maurício Reis, the school would today be a parking lot, adding dryness to the already naturally arid island. The School of Natural Cinema project, which Francisco Janes set up with the founders of PORTA33, is the perfect example of the pedagogical capacity of art and art institutions, which serve here as mentors, facilitators and enablers, managing skills, stimulating curiosity and finding space for skills to awaken from the dormancy to which they have been voted consigned due to the lack, until then, of resources and structures capable of doing so. We realized, in this way, that Janes’ videos are the result of many excerpts captured by the students who took part in Escola do Cinema Natural, and that the polysemy and polyphony they incorporate are justified there. Janes takes the risk of dealing with results that may not be entirely satisfactory, but the goal is never about the result. Rather, it means working on a radical form of generosity that overcomes schisms and prejudices about artistic activity, proposing a praxis that is more communitarian than solipsistic.

The frames follow one another. There is a glare in the fleetingness of time. Each video is a rhizome that gradually expands, suggesting multiple narratives and developments. The artist is just a facilitator, a mediator, someone who pushes for lifelong learning and informal education. This investment may stop there, as an isolated act. But if that’s the case, it’s worth it. Other initiatives will be launched, different ones, for sure, but with the same intensity and passion for life, in which art comes out of itself and allows itself to be contaminated by the uncertainty and evanescence of everyday life, of vital flows, human and non-human. The beauty of these videos and sounds is the crackle of life, the imperfection of the hand that wants to do something, and do it well, but fails to do it perfectly. Jacques Ranciére would certainly know how to put this reflection more eloquently. However, writing and language are also perfectly imperfect.

Back at the table, a bottle is poured, and arms reach across plates in search of more food and drink. The conversation is always inexhaustible. We got to know the Trégua project and the work they have been doing with people deprived of their liberty. There are moral and ethical doubts that make us question the relevance of prisons, their purpose, and the life possible behind bars. Can Art serve as a link between two such asymmetrical realities? Can Art serve the purpose of social integration when many prison institutions seem to fail in this regard? Trégua is a curious project, deeply political and radical in what is done in Portugal and within the social and hybrid practices of art.

The Quimera Collective challenges us with the local artistic reality and the work that young people have to do to make a name for themselves. When opportunities don’t arise, they are invented together, seeking out and using each other’s strengths. RAUM presents a copy of one of its editions. The format deconstructs the sequentiality of the publication, with loose sheets and drawings, and texts that juxtapose each other, challenging the usual logic of the book.

Air plants swing from the ceiling in search of moisture. Everyone talks about the hanging garden of PORTA33 and Cecília – a magical place, they say. And then we went up the stairs, in private, and carefully hopped up to a shed full of green beds and pots: bougainvillea, birds of paradise, more air plants, succulents. Nature finds its way into foundations, beams, pillars, and nets. Cats walk nimbly through the glass roof. We sit in this makeshift paradise and talk about flowers and plants, and landscapes. We step out of time and find reality strange. Everything is abundant on this island.

BIOGRAPHY

José Pardal Pina has been the associate editor of Umbigo since 2018. He has an Integrated Master's in Architecture from Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, and a Post-Graduation in Curatorship from Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. Curator of the Dialogues (2018-2024) and Landscapes (2025-) projects in Umbigo.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

14 May 2025

Does the potato dance?

By António Figueiredo Marques

Next

article

14 May 2025

Various Others 2025, a travelogue

By Laila Algaves Nuñez

Related Posts