article

Torcer, Amarrar e Pender: An Articulated Narrative

In her solo exhibition Torcer, amarrar, e pender, Sonia Gomes evokes a kind of hermitage, sanctifying all that the modern world has come to devalue: solitude, slowness, silence, attentiveness, and tenderness. A withdrawal from the world, not as an escape, but as a way to clarify and refine our relationship with the multitude of meanings that now remain “outside.”

I sometimes spend an entire morning trying to recall a dream I had. Only fleeting images flash across my mind - brief, elusive - and the harder I chase them, the more they slip away. Still, though I cannot hold the images, the dream’s feeling embraces my being. In the end, when I understand I cannot capture these images, I settle for the feeling alone.

Brazilian contemporary artist Sonia Gomes’s solo exhibition Torcer, amarrar e pender at Kunsthalle Lissabon felt like a journey to the very source of those images I have long chased in vain. If you look long enough into the layered twists of works, you begin to feel swept into a vortex, a place where a remarkable sense of balance quietly accompanies you. This balance doesn’t reside in a fixed point; it may be found in the feet, the body, or the topmost edge. Gomes’s balanced complexity does not unsettle; it grounds. This is the kind of complexity we need: one that resists, that speaks out, that rises up, and makes us feel it stands quietly by our side.

In his novel Slowness, Milan Kundera offers a metaphor: when we try to remember something, our steps slow down; when we wish to forget, we move faster. In Gomes’s work, I sense a slowness, a gentle rhythm through which memory rises to the surface. This act of remembering becomes a way of re-creating the past, preserving time like a singular, unbroken treasure.

Within knots, objects from past generations (now obsolete in the eyes of the modern world) gather: prayer beads, tassels, buttons. Stripped of their original context, they persist with a quiet yet unwavering determination. Some sewing materials - spools, threads, needles - are tucked away just as they are, untouched by transformation. A declaration of raw existence. A message insisting on simply being, without the need to become anything else. In the pores of the fabric, we can still feel the breath of a past that remains alive, still pulsing.

Since childhood, I watched in awe as fabric transformed in my mother’s hands - she was a seamstress. Each time, this process filled me with wonder. Fabric was never merely a material that covered parts of the human body; it was also a reflection of thought, tradition, belief, and a philosophy of life. The works of Sonia Gomes, brought to life through her hands, reawakened that same childhood fascination. In her practice, the artist’s thoughts seem to translate directly into the material: its softness or rigidity betraying her inner world. Branching with knotted joints, these forms resemble the axons and dendrites of a nerve cell: structures made to feel, not simply to be.

The stitches where the fabrics meet are left visible. Unlike the hidden seams of conventional clothing, these joining points are deliberately exposed. This openness invites transparency, urging us not to conceal the precious accumulations of our subconscious but to honor and reveal them.

A language born in knots

In an era marked by the most ferocious waves of consumerism, I’m reminded of Roland Barthes’ words: “All production is creation, and thus ‘good’; all consumption is destruction, and thus ‘bad.’”

According to this simple equation, imagination gives rise to a powerful form of expression: a discourse shaped by spontaneity, one that resists life’s measured, proven, and documented structure.

Gomes’s work unfolds through two primary natures: one plastic -malleable and sculptural; the other linguistic. Fabric stiffens where it is tied or and softens where it hangs. From these knots, a discourse emerges: one that honors labor, survival, and the value of craft. Within this whirl of color and form, we glimpse the abstract, translucent, yet deeply felt nature of creation itself.

What is made here is the structure itself, formed at the level of material and its transformations, not its representations or meanings. Why does fashion speak so obsessively about “clothing”? Why does it insert an authoritative web of meaning between the object and the consumer? As we know, the reason is economic. The calculating industrial society must produce consumers who do not calculate. It is not the object that incites desire, but the name; not the dream that sells, but the meaning.

“E depois, o sol começa a brilhar”

In this small painting, we find ourselves watching light emerge from a camera obscura. Reality and reflection feed into one another, until the two become indistinguishable. The boundary between the observer and the world begins to blur. One of the most compelling functions of the camera obscura is its ability to detach the act of seeing from the physical body, making vision bodiless. Sonia Gomes’s E depois, o sol começa a brilhar evokes this bodilessness, allowing us to observe the world as if vision itself had been abstracted into pure gaze. Gomes invites us to see, because light, above all, is about seeing.

Similarly, in the work titled Cadeira, we encounter a state of interweaving. Colors mimic fabric, fabric mimics colors, until they come together as a whole. As a result, Cadeira offers the promise of a place. It gestures toward the struggle of the Frente de Luta por Moradia (Front for the Housing Struggle), a movement that opposes the systemic denial of one of Brazil’s most fundamental human rights: the right to shelter. In 1997, the occupation of an abandoned building Nove de Julho in São Paulo marked a turning point. By 2000, the women leading various occupations came together to form the Movimento Sem-Teto do Centro (MSTC), mobilizing and organizing unhoused families.

Housing, here, is far more than a matter of property. It speaks to rights that no one should be deprived of - belonging, safety, continuity - and becomes a declaration of independence. Cadeira recalls Virginia Woolf’s “room of one’s own,” that sacred, unreachable space that no one can access or take away. A place all others, especially women, need to create and move forward.

In her solo exhibition Torcer, amarrar, e pender, Sonia Gomes evokes a kind of hermitage, sanctifying all that the modern world has come to devalue: solitude, slowness, silence, attentiveness, and tenderness. A withdrawal from the world, not as an escape, but as a way to clarify and refine our relationship with the multitude of meanings that now remain “outside.” It becomes a point of convergence, where philosophy and imagination meet in a deliberate knot.

The exhibition is on view at Kunsthalle Lissabon until August 16.

BIOGRAPHY

Ayşenur Tanrıverdi is an Istanbul-based writer, living in Lisbon since September 2022. She studied at Istanbul University and is the author of two published works of literary fiction. A regular contributor to Cumhuriyet, a major Turkish newspaper, where she focuses on Portuguese culture. Her essays and critical texts on theatre, literature, and contemporary art have also been featured in various art magazines.

ADVERTISING

Previous

column

07 Jul 2025

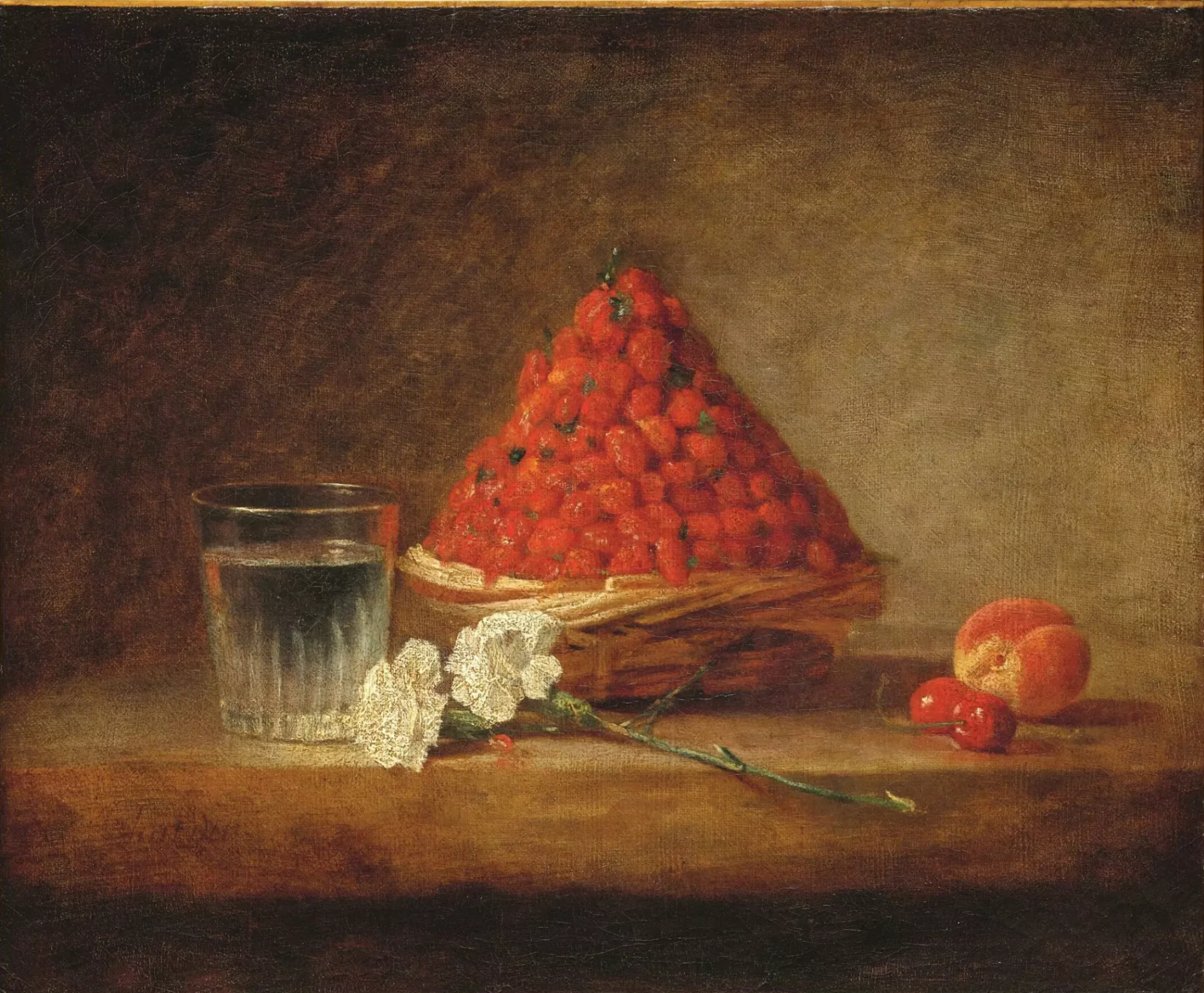

Mixed media on paper #10 - The strawberries of the saison

By Luísa Salvador

Next

article

14 Jul 2025

Life and other forms

By Filipa da Rocha Nunes

Related Posts