column

Mixed media on paper #10 - The strawberries of the saison

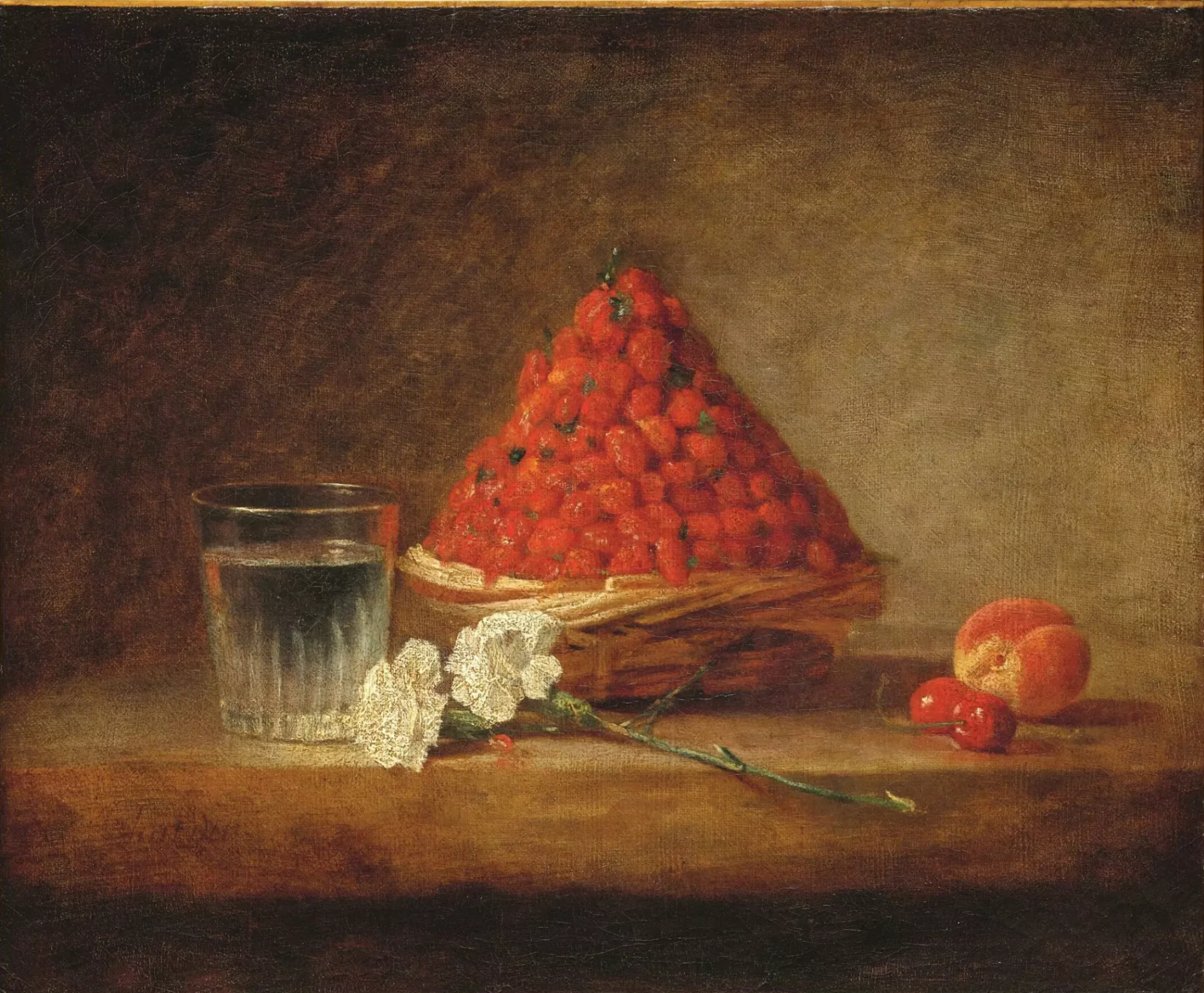

In the summer of 1761, Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699-1779) presented his composition "Le Panier de fraises" no "Salon Carré" in the Louvre in Paris. It was one of the painter's last still lifes, at the height of a renowned career that spanned all of Europe, with prestigious clients and commissions.

In the summer of 2025, Jonathan Anderson (1984 -) presented his collection for Dior Homme at the Hôtel des Invalides, also in Paris. It was his first collection as creative director of Christian Dior, at the height of a career as a designer for other fashion brands, notably his own, JW Anderson, and more recently, Loewe.

These two seemingly distant moments, both temporally and conceptually, have something in common. Strangely enough, or perhaps not so strangely, some of the spectators at the Dior Homme show on the 27th of June, 2025, noticed that there was a very particular, vivid and out-of-place painting in the room, anachronistic to the moment that was unfolding. It was Chardin's painting, Le Panier de fraises. We'll come back as to why. First, let's look at some information about this curious painting.

With a relatively simple and uncluttered pictorial composition, Le Panier de fraises (1761) is a beautiful example of what a still life can be. With only a few elements represented, this painting captures the vibrant characteristics of a given season — summer. Strong and saturated tones, a search for the light of dawn or dusk, so as not to confront the high temperatures of the rest of the day. The apparent simplicity of things that have strong attributes: lots of colour, lots of flavour, because the sun and the warm temperatures of the season give them these characteristics. Panier de fraises celebrates all this summeriness.

The central element is a wicker basket topped by a well-balanced pile of small strawberries, but full of colour and, supposedly, flavour. It is almost a pharaonic monument that can be glimpsed there: a pyramid of intense red, an elaborate construction, made up of a multitude of small elements. Each strawberry, a small cone, a small irregularity that could, at any moment, bring down the entire composition. What unstable and shiny fruits these are! Beside it, also placed on the same wooden table, is a glass of water, of basic appearance, fitting in the banal everyday life. Glass and transparent liquid, but the hint of refreshment in the liquid gives a haze of opacity to the glass. We are looking at a glass of fresh water. Ice cold, even. Crossing these two elements, placed on the surface, are two white carnations. Fresh flowers, which at the time were a kind of princess among flowers, were only dethroned by roses, the queens of the floral world. But in Chardin’s painting, there is a resounding confirmation that the season depicted is indeed summer: opposite the glass of water, a peach and a pair of cherries can also be found. Both hot-climate fruits. I couldn’t help but be intrigued — this is not how I recognise summer and its fruit.

One of the things I like to check most when I see a still life is its seasonality. Still lifes tell us a lot about habits, landscapes and principles. There is an example of a painting from the mid-17th century in the Netherlands in which an orange appears among some objects. The orange was not an ordinary detail. It revealed the patriotic tendencies of the painter who conceived it. The orange was a symbol of autonomy, a metaphor for the strength of a royal house in a divided country. With Chardin's basket of strawberries, we will never know if there was some similar political meaning in the choice of this fruit. But it tells us that in the summers of the 18th century, strawberries were a seasonal fruit. I am sensitive to the cause of strawberries, because, as I was born in May, I always had strawberries at celebrations. Recently, I have noticed the phenomenon of strawberries appearing earlier, sometimes arriving as early as March. Suddenly, May is the season for cherries, something that throughout my childhood, adolescence and right into adulthood was a summer fruit. It was the harbinger of the arrival of that season, along with apricots, nectarines, peaches, plums, and many other strong, vibrant, and sweet fruits. And so the phenomenon has been arriving sooner. With this painting, Chardin informed a 21st-century viewer, in this case me, that strawberries were synonymous with summer. I have to admit that this will depend on the geography. For example, in a BBC article from May this year, it is predicted that 2025 will be an excellent year for strawberries in England. The combination of warm days and cool nights are known factors that make strawberries sweeter. With the cool night temperatures, strawberries rest, putting all the energy they have during the day to produce more natural sugars. This seems to be an explanation. It makes sense that in Portugal they arrive earlier, with the recent temperatures observed here when summer finally arrives. Our spring will have characteristics that are more favorable to the development of strawberries. And so, unintentionally, Jean Siméon Chardin reveals to us the changes in climate in a short period of centuries.

Chardin painted and presented Le Panier de fraises at the Palais du Louvre, which in the 18th century was not yet the museum we know today but was already a place where several Salons of painting and sculpture were organized. Le Panier de fraises, when presented at the Salon Carré in 1761, was highly praised and admired by the artistic fringe of society at the time. Denis Diderot wrote about this painting, which was equally appreciated by the Goncourt brothers. They describe a still life that revealed the very substance of the objects, the air and the light, organized and tidy, in contrast to the “beautiful disorder” of other previous paintings by the painter. Indeed, this still life has something of a contradiction. On the one hand, one admires the rigor of the composition, the clarity and extreme care in the representation of the elements, the softness of the realistic details. But it is also a painting of extreme sensuality, in that it captivates our senses, between the vibrant colours and the suggestion of the sweet taste of the fruits. It is bold in its duality.

Last year, Chardin was once again in the spotlight. The painting Le Panier de fraises, after many years in the possession of the same family, was put up for sale. It was in danger of leaving France. In a marketing and patronage move, the Musée du Louvre decided to launch a campaign to acquire the painting. Two thirds of the purchase price was guaranteed by the LVMH group, another third by the Louvre, and surprisingly, ten thousand people contributed the remaining third in their own right. Around 1 million three hundred thousand euros, with an average donation of one hundred euros per person. The Musée du Louvre is currently the owner of the painting, which is to say, the French State. Le Panier de fraises, called a “National Treasure”, has not left France. On the day that Jonathan Anderson introduced himself as creative director of the house of Dior, a brand of the LVMH group, Panier de Fraises was in the room. On loan to the patron group that was responsible for much of its acquisition, the painting’s presence was a demonstration of power. Who knows, maybe strawberries will now also become a metaphor for other subjects outside the artistic spectrum. But for now, if there were any doubts, Le Panier de fraises is a painting that celebrates the beauty of summer. And what a rich treasure that is. This saison seems to be, after all, about what strawberries can do.

BIOGRAPHY

Luísa Salvador (Lisbon, 1988) is a visual artist and researcher. She has a PhD in Contemporary Art History from NOVA FCSH, having been awarded a scholarship from FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology (2015-2019). She has an MA in Contemporary Art History from NOVA FCSH (2012) and a degree in Sculpture from FBAUL (2009). In parallel with this activity, she develops her artistic practice. She has been exhibiting regularly since 2012. She won the Young Creators Award 2018 in the Visual Arts category. Alongside her artistic practice, she also writes, including theoretical texts and chronicles. In 2018 she founded the quarterly publication "Almanaque - Reportório de Arte e Esoterismo", of which she is the editor. She lives and works in Lisbon.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

©photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio-7yoip.jpg)

03 Jul 2025

Sex and Solitude by Tracey Emin: Radical Womanhood and Shared Viscerality

By Orsola Vannocci Bonsi

Next

article

-94e37.jpg)

11 Jul 2025

Torcer, Amarrar e Pender: An Articulated Narrative

By Ayşenur Tanrıverdi

Related Posts