article

The cause and chance

"Perhaps there is, in fact, no great difference between study and play, or between intellect and experience, for what matters, as Longinus said, is talent: that which is learned without being taught, in the systematization of experience. The artist is the one who knows how to pay attention to life itself, for art is not like science—it does not seek objective truth, but the subjective experience of a truth."

In the two initial works in the Juntos exhibition, one perceives the field of synergies and ruptures cultivated by the couple formed by Helena Almeida and Artur Rosa: in 1971, they each paid homage, in a work, to the esteemed Portuguese Baroque painter Josefa de Óbidos. In a volumetric grid of expansive vectors, Rosa segments the painting O Menino Jesus Salvador do Mundo into various depths to both preserve the hierarchies of the original and tension the straightness of its lines with the voluptuousness of Josefa's figures. Almeida, on the other hand, prefers a freer dialogue with the artist: a collection of soft sculptures that subvert the compositions of Josefa's works to better evoke the exuberance and discomfort of her still lifes, which pile cakes and petals into scenes of childlike affection and quiet hostility. It would be convenient to reduce them to opposing archetypes—the meticulous logic of an Apollonian Rosa and the free experimentation of a Dionysian Almeida. More interesting, and perhaps fruitful, would be to try to overcome the simplicity of labels to find improvisation in logic and rigor in chance.

Located in one of the exhibition's first rooms is a series of early works by Almeida that, to the untrained eye, would seem more like Rosa's—although they don't operate under her principles. In general, the attentive artist knows how to select the methods and materials that best align with the temperament of his practice: the works of a cerebral Rosa would certainly be mechanisms constructed impersonally, while Almeida's photographs present us with the spontaneous gestures of an experimental artist. But then what can we say of Almeida's Sem Título, where wooden constructions and rigorous paintings contrast with her usual vitality? And yet, here a central theme of her later practice is already revealed: the crossing of boundaries. In all of them, she explores the arbitrariness of cuts and expresses more interest in the zone of contact between two entities than in the perfection of internal control, in visual games that already contain the spirit of playful calculation present in the artist's most mature period. Later, in Desenho Habitado, he would argue that every straight line is imperfect because there is neither an impeccable support nor a mechanical subject: we draw in a world of chance and singularities, and it is richer to move between things, weaving together distinct phenomena—the essential thing is tension: he is not interested in absolute freedom, but in the experience mediated by circumstances, in the contact between the individual and otherness. His own face is found outside the canvas in Estudo para Tela Habitada, suspending it not on a flawless wall, but on a body moving in the world, suggesting that perhaps the most important thing lies outside the cutout.

In Rosa, however, there is no mediation, for there is no chance—only causality. More classical than Almeida, he is interested in the proportions that once illustrated the harmony of a stable cosmos. Although primarily abstract, in the series Linguagem Logarítmica he uses Almeida's preferred colorless photography not to photograph performances, but to dialogue with the Renaissance mathematical space. Perhaps it evokes Alberti's solitary eye, which, poised up to the pictorial window, contemplates a scene of impeccable composition, the cosmos organized by the intellect. But in Rosa, the perfect grid that emanates from us is not fixed, but mobile, projecting itself like a cascade of solids: it abandons the linear grid of classical perspective, with its immutable forms, for the logarithmic grid of multiplicative expansion, which best represents modern physics and its perpetually expanding universe. From the closed cosmos to the open universe, from composition to rhythm.

Such dispersion would indeed impede classical cohesion—but Rosa accepts neither the unpredictable nor entropy: it is Almeida who does this, understanding the cut as an invitation to transgression. He is more scientific; his framing creates controlled environments where the intellect operates unhindered by chance. For Almeida, movement is the engine of change. For Rosa, it is the revealing of environmental conditions, their causes and effects. Hence his interest in geometry, in bodies reduced to intellectual lucidity and clearly manipulable by it, while Almeida prefers the human body as the locus of total experience. There are no surprises in Rosa's environment—only an undisturbed succession. Yet, it could still promote final dispersion. Instead, he chooses to reinforce cohesion: their trajectories are cyclical, as solids, after being twisted, return to conciseness. This pendular, replicable gesture almost reminds me more of the Greek cosmos appropriated by Nietzsche's Eternal Return than of the modern conception of the universe. In many of his titles, he already advances the gesture's logical conclusion: From the Da Reta ao Triângulo. Even when he allows himself to superimpose limits, he does so logically, as in A Pirâmide e o Papel Cortado, where the cuts in the paper follow a staggered order, line by line. Rosa updates, but perhaps does not subvert, the Renaissance logical space, as he seems unwilling to relinquish absolute control.

In Ouve-me Almeida also works with a closed system, but only to expand, in an experimental process, the elegant silhouette created by the solitary subject, accepting the chance that even comes from intimate dialogue: in this work, it is the couple's breaths that corrupt the figure. For if for Rosa, limits are the end, for Almeida, they are only the beginning. In Saída Negra he explores the indistinct current emanating from the human, moldable only in part, which ultimately marks us back. In Mão atravessada por uma caixa a blow destroys the fragile geometry of a paper box—the free experience of expressive gesture overcomes intellectual imposition. But, in the end, the hand finds itself tied by the thread that delimited the box's edges—the subject, too, is transformed by the experience, for in Almeida, action is not imposed, but mediated: his interest is the beneficial contact between figure and background. The wall is an expanded plane, and the baseboards, its margins—hence her interest in exploring them in performance: the individual's existence alters all limits. There is no outside, for everything is within; the human alters and is altered by the environment, and every line is the margin between what we are and what we can be. And if the individual's reality is experience, the gesture of the hand is truer than the silhouette of the face: in Dentro de Mim, Almeida reveals her own face with a brushstroke. Rosa, in her Auto-retrato, doesn't so much conceal as simulate blurring. The fragmentation of the silhouette seems to suggest its gestalt, or total image, from the pieces. Here, I don't see the imponderable, but rather the mental clarity of the suggested image.

Experimentation presupposes an absence of clear objectives, while the emancipated intellect is a projectile that, in its search for the chosen outcome, articulates everything between causes and effects. And yet, Rosa, too, in certain works, does not so much accept chance as maintain it as a possibility: in Evolução, a mechanism not yet activated retreats into the latency of its possibilities—would its movement be altered by circumstances or would it relentlessly cut through its surroundings? Could this grain of doubt diminish Rosa's usual precision? Perhaps there is, in fact, no great difference between study and play, or between intellect and experience, for what matters, as Longinus said, is talent: that which is learned without being taught, in the systematization of experience. The artist is the one who knows how to pay attention to life itself, for art is not like science—it does not seek objective truth, but the subjective experience of a truth. Perhaps Rosa, then, is like Almeida, deep down: his art is the experience of his principles, in motion. Was he performing with geometry? In this sense, I almost see him as more relaxed than Almeida, because to her, every gesture is of the utmost importance—she studies the possibilities of the human in a world of chance and limits. From the beginning, when he was still dedicated to a more geometric practice, Almeida pondered the importance of logic in a world where each space preserves conditions particular to the human—perhaps he needed to begin with a dubious logic to later reach a significant doubt, while Rosa perhaps prefers the delights of a mathematics of impeccable simulacra and optical impacts that care less about the validity of rational premises.

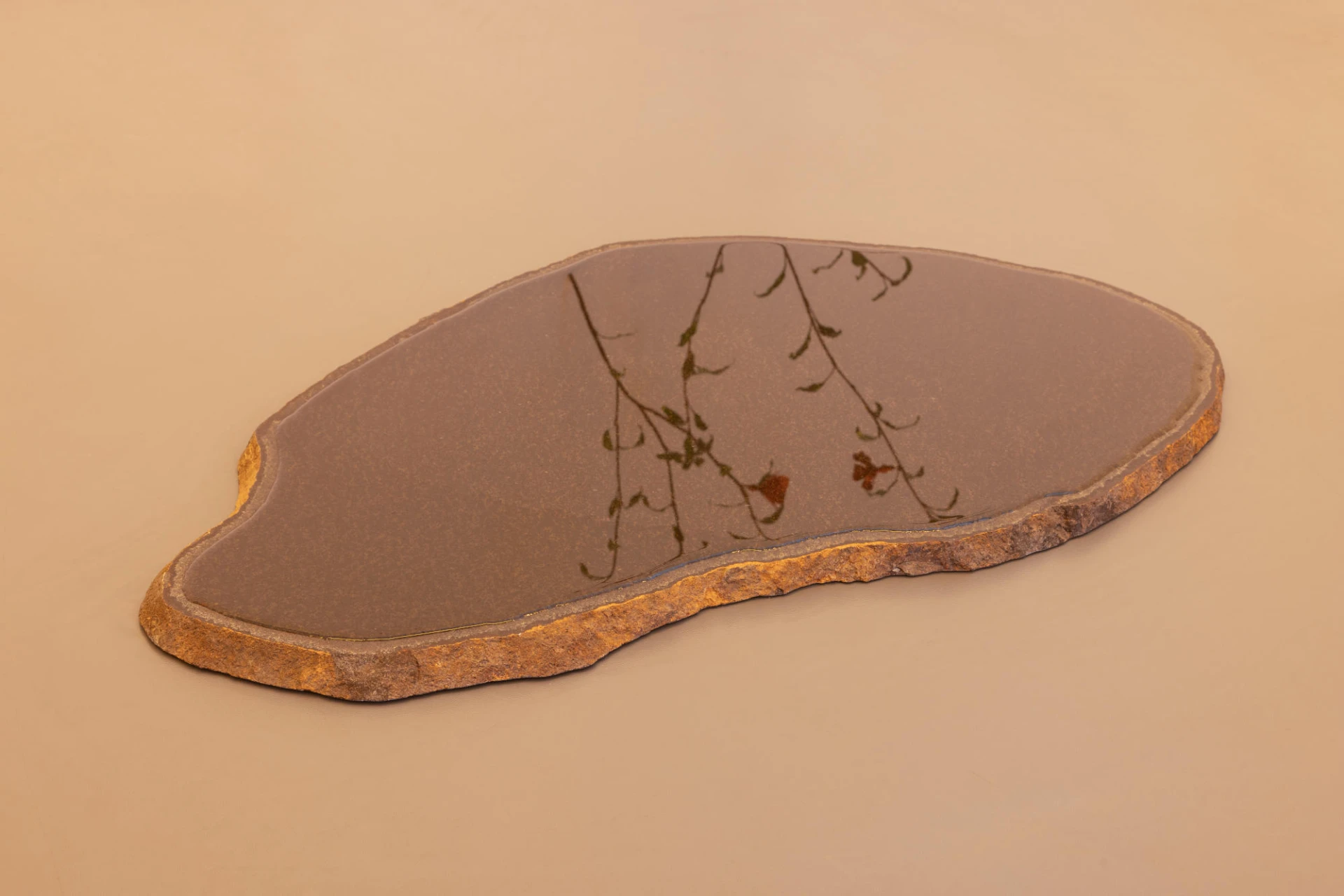

In addition to Juntos, the CAV exhibition space is completed by the show Eu paisagem (I Landscape), by Andreia Nóbrega. Although these are two distinct shows, it is possible to discern revealing similarities between the three artists. Nóbrega's longitudinal panoramas unfold, extensive, as the result of a continuous experience that understands the landscape above all as a collection of patterns, articulating the unfolding of vegetation almost with a textile logic, like tapestries, where the slow addition of units suggests meshes not entirely distinct from the graphic patches of op-art sometimes favored by Rosa. To browse his works is to perceive rhythmic shifts, but here there is more naturalism, more permissiveness, less intellectual dominance. In Nóbrega, there is intuition in control, and the impact we feel when contemplating his landscapes is precisely that of enchantment with the tension, never resolved, between the possibility of order and the imposition of chaos. In this, and although distinct, I recognize at least one similarity with Almeida's temperament: the continuous experience of the artist who seeks that which is only true because it can never be fully resolved.

The Juntos and Eu Paisagem exhibitions are curated and written by Miguel von Hafe Pérez and are on display at the CAV in Coimbra until September 7th.

BIOGRAPHY

Tomas Camillis is an author and researcher based in Lisbon, working on fiction and on essays in the interplay between art, philosophy and literature. He has a master's degree in Art Theory by PUC-RJ. In recent years he has participated in researches, taught courses in cultural institutes, helped organize conferences and published in specialized magazines. He currently collaborates with the MAC/CCB Educational Service and Umbigo magazine.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

25 Aug 2025

Despite everything, we shall continue

By Maria Inês Augusto

Next

article

27 Aug 2025

Notes on a finished photography

By Tiago Leonardo

Related Posts

[A] Guilherme Parente, [L] FCC-bj2nj.jpg)