article

Nothing to Learn, Everything to Teach

After being tempted with banquets and riches, with visions of war and the offerings made to him by the dazzling Queen of Sheba, it is the wise Apollonius who penetrates deepest into Anthony—suggesting that the hermit's thirst for knowledge was stifled by his stubbornness in isolating himself from the world, in a desert that offered him nothing but hallucinations. “Sometimes torpid, sometimes furious — they remain forever in my conscience,” Anthony admits. “I crush them; they rise again, they stifle me; and sometimes I think that I am accursed.”[1] Flaubert's strangest novel, The Temptation of Saint Anthony presents us with a mystic in agony, divorced from the spiritual serenity he once knew. His search for epiphany is hampered by nocturnal demons who promise him every advantage, every pleasure. The saint repels them, one after another, in an ascetic obsession that borders on insanity.

I suppose that Anthony's strength would have been, to Flubert, the ideal tonic for the modern world, with its conformist materialism and cynical hedonism. In our daily lives, the madness of the anchorite is almost inconceivable. But the artist can still be seen as a monastic figure—amidst appealing images and the spectacularization of events, there are always those who are willing to preserve sensitivity for the simple promise of some small achievement, a glimpse of the genuine. This sentimental education (Schiller called it aesthetic) resembles the madness, and eventual despair, of the mystic — it is no wonder that other eras saw the artist as having a Saturnine disposition: melancholic and temperamental. Even a skeptical artist may end up retaining a certain idealism contrary to the mundane practicality that seeks to silence our conscience to provide us with advantages in the world—for the artistic quest is precisely the awakening of consciousness as an end in itself, with no ulterior motives.

“I'm not sure if it's because of the political climate in the United States or the negative changes in our neighborhood, but the new work is more about change, rejection, and imprisonment,” Tim Rollins tells us about the series The Temptation of Saint Anthony, created with the KOS group based on Flaubert's book. “The kids and I position ourselves as Saint Anthony in relation to the things that happen on the streets. If a kid wanted to drop out of school and make hundreds of dollars a day selling crack, he could easily do it.”[2] In 1982, the artist began a fruitful art education method at a public school in the Bronx with a group of children deemed unsuitable for formal education—the eventual Kids of Survival, with whom he worked throughout his life. Through an artistic practice stimulated by reading literary classics, he sought to circumvent the standardization of school culture. The modern artist is, after all, anti-utilitarian, invested in a practice without precise limits or clear objectives, built on a routine of contemplation and free thought. (It will be up to another article to analyze the real validity of a practice closely linked to conceptual art—which requires a certain maturity of thought from the artist—and which, built on a dynamic of invariable inequality between an adult and a group of children, is neither solely artistic education nor solely professional production. How can we discern the relationships between the teacher and the artistic collaborator, or between children's experimentation and the obedience of students as workers? From the early Frankenstein/Dracula to the later works, there is a noticeable growth that I am not sure is due to the children's progress or to Rollins' greater management. Even so, many of the works are like school assignments: collections of variations on the same central element of the stories, to accommodate each child's expressiveness—the scarlet letter sewn by Hester Prynne, the golden trumpets of Amerika, Oberon's flower in A Midsummer Night's Dream.)

Flaubert based his work on a painting by Bruegel the Younger, which depicts strange creatures swarming around the hut of the notorious recluse. His book also emphasizes the artistic possibilities of Anthony's hallucinations, its plot filled with scenes conceived by an author in the free flow of his imaginative impulse. Perhaps this is Anthony's artistic appeal: the paradox between his hermetic commitment and visual exuberance. But had the saint himself painted, I suppose he would have preferred abstract art, detached from a world he no longer intends to represent to find himself in purity—the anchorite also controls himself by nullifying circumstances, in a self-referential exile in contact only with the eternal: he is as abstract as he is abstracted from the world. But he is not a square — a contradictory human being, Anthony is plagued not only by external mirages, but also by intimate impulses, repressed in his life of deprivation: if God can be seen as an internal principle in mysticism, the devil is also an internal fury. Like an abstract circle seduced by figurative images of apples and full moons, Anthony, too, questions his exile in the face of life's exuberance.

But could spiritual turmoil be a path to epiphany? Tim Rollins/KOS's work The Temptation of Saint Anthony consists of a series of prints composed of two main techniques: (1) the base, which is always the same, consists of a photocopy of an exceptionally violent passage, overlaid with (2) abstract graphic stains, all unique, in watercolor. The mystical hermit perceives the disarray between the planes and seeks to adjust his errant behavior to find channels still open to the divine—this work translates that fundamental condition. The literary base is its superior dimension, the eternal word that does not change: the use of photocopying, with its technical precision and reproductive infinity, gives the series the impeccable succession of the same image, as if transcended from time. The top layer, however, is earthly, belonging to circumstances: the watercolor technique favors shading (like the hues of a confused spirit) by Rollins/KOS manipulated in experimental, almost automatist techniques, thus exploring the human's inherent imperfection and lack of control. Each stain is the result of a distinct gesture, always unique and never flawless, spontaneous yet contracted, developing its own relationship with the text behind it, perhaps violating it as a meta-commentary on that passage's content. The work's small graphic scale, centered on white pages, reinforces the mystic's exile, his obsession, and his immanent struggle.

Flaubert's The Temptation was also illustrated by Odilon Redon in lithographs that certainly influenced Rollins/KOS — Redon's symbolism elevates the scenes to the interstice between the figurative and the abstract, in graphic patches that blur the forms of things. Through the different artistic approaches to Anthony's story, it is possible to represent both the saint's successive isolation and the historical blossoming of abstract art in the West: (i) Bruegel and Bosch present us with a figurative saint set in a concrete yet fantastical landscape, (ii) while Redon haunts him monochromatically in closed rooms or abstract spaces, (iii) and Rollins/KOS ultimately favor perhaps the saint's inner self, in the abstract flows of the everlasting struggle of primal forces. There is therefore an artistic break between Redon and Rollins/KOS: the latter no longer represent scenes from the plot, but rather prefer to explore their themes visually. “We don't illustrate the texts,” says Rollins. “It's about creating a visual counterpart. Something that captures the spirit of the text or relates to its issues. We are literary, but not literal”.[3]Redon respects the text, including its physical appearance: it occupies blank pages. Rollins/KOS, on the other hand, embrace modern indulgence and superimpose themselves on the written words, thus creating a tension that accentuates the violent dilemma of the anchorite.

Is it a collection of feelings? As an abstract, and therefore anti-narrative, series, it contradicts the very idea of literature on a broader level. But the modern novel, with its realistic impetus, although it does not abandon history, nevertheless approaches self-reference, sometimes seeking to mean nothing beyond itself. Proust admired Flaubert's objectivity, who dreamed, as we know, of writing a story about nothing—an indifferent book, pure form, without commentary or arguments, fulfilled in its own appearance. In The Temptation, he is entirely in the symbolic realm, but the heroic simplicity of Anthony also contradicts both the poetic richness of the narrative and its numerous theological arguments. Moreover, the frenetic succession of events ends up emptying its content, as taught by the theory of the sublime: an excess of form generates mental confusion — and isn't the accumulation of images a way of enchanting us beyond the intellect, generating prose that neglects information in favor of aesthetics? Herberto Helder preferred novels that he called interrogative machines. Answers are secondary—asking questions is vital. At all times, Anthony questions his visions' validity. “Are there really such things on earth?” he wonders upon hearing Apollonius's account. The question arises from within, from doubt in the face of life's mystery, opening the world to reflection. An answer should not be stated, but felt, so that it does not close the question. In the book, Anthony's most memorable achievements are not understood, but felt, in moments of great beauty. Rollins often spoke of beauty as a beacon for political art, to escape prescriptive activism and journalistic information. He rejected what he saw as Georg Grosz's caricatured crudeness in favor of William Morris's healthy balance. “How can you make a work of political art that is not negative, but beautiful? It is much harder.”[4] There is an educational slant to all his work, although his pieces are not didactic — rather than teaching, he prefers to give viewers the opportunity to teach themselves.

The exhibition The Temptation of Saint Anthony, by Tim Rollins & K.O.S, is a project by UPPERCUT and can be visited at Buraco until December 6th, when the first Educational Service session, designed by Lea Managil, will take place.

[1] Flaubert, Gustave. (2023). A Tentação de Santo Antão. Minotauro, p. 76. Translation from: The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Temptation of St. Anthony, by Gustave Flaubert, Translated by Lafcadio Hearn, Illustrated by Odilon Redon

[3] Id., ibid.

[4] Id., ibid.

BIOGRAPHY

Tomas Camillis is an author and researcher based in Lisbon, working on fiction and on essays in the interplay between art, philosophy and literature. He has a master's degree in Art Theory by PUC-RJ. In recent years he has participated in researches, taught courses in cultural institutes, helped organize conferences and published in specialized magazines. He currently collaborates with the MAC/CCB Educational Service and Umbigo magazine.

ADVERTISING

Previous

agenda

28 Nov 2025

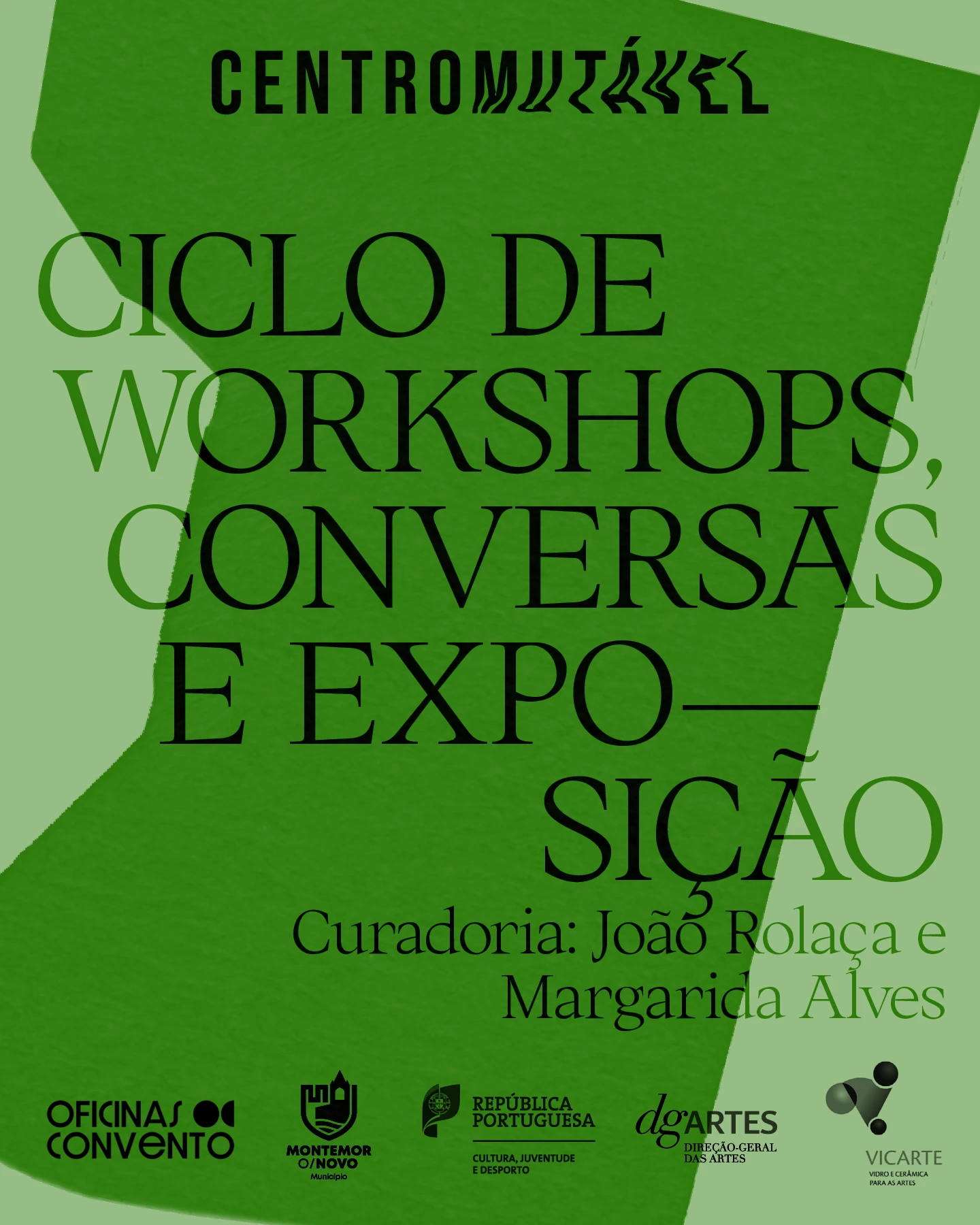

3rd Edition of Centro Mutável, in Montemor-o-Novo

By Umbigo

Next

agenda

02 Dec 2025

Artistic directors for the Sequences 2027 biennial announced

By Umbigo

Related Posts

[A] Guilherme Parente, [L] FCC-bj2nj.jpg)