article

A sweet repulsion: Bartolomeu Santos, at Espaço Cultural das Mercês

If we were the wolf of the ancient story, we would be excused for understanding the exhibition THREE LITTLE PIGS, AND EVERYBODY ELSE not as an examination of the grotesque plasticities of twisted organs and viscous structures, but as a collection of delicacies arranged in an aseptic space to reinforce the impact of their deliciousness—perhaps they contain a formal hybridism akin to both abstraction and figuration, perhaps they promote an abstractionism whose heightened suggestiveness also stimulates concrete allusions and reflections.

Made of sponges, they retain a soft roughness still perceptible even after the epoxy coating, which lends them a shine capable of nuanced the repugnant into something more akin to confectionery, like a glaze preserving the tender contents. I see in these works the influence of artists like Belén Uriel and Mona Hatoum, who articulate the ambiguity of attractive and repulsive objects, in a strangeness that suspends immediate meaning. To polish the disturbing is to inhabit this space where the gustatory aversion and funereal interest of the gastronomy of figures like Brillat-Savarin or Grimod de la Reyniére also converge. But if the banquet is a ritual of excess, Bartolomeu Santos's exhibition displays them with clinical concision. By punctuating the works in this hospital space, covered in white paper, it transports us to a state of asepsis that envelops everything in an analytical aura. Thus, the works also end up stimulating the viewer's placidity in the face of the object's strangeness.

Could this also be a metaphysical placidity? Roman haruspices used to inspect the organs of sacrificed animals, divining divine designs. The Mesopotamians also explored such omens in their study of liver shapes, and near Piacenza, an Etruscan diagram was discovered as an oracular guide to the analysis of sheep livers. If the universe is a massive body where all its parts maintain harmony, then the viscera also reveal the overall picture. Could the heterogeneous chromaticism of these pieces, their surfaces composed of overlapping tonal patches and distinct textures, be an allusion to the cosmic landscape, with its constellations and nebulae?

Plato didn't seem to be interested in such anatomical practices, but he also believed, in his own way, in the direct link between the intimate and universal truth—both the intellect and its world of forms were fond of geometry, a discipline of rational constructions whose perfection is absent in nature. With its structure of ascending geometry THE WAY HOME is like a ladder of Platonic solids, still in its infancy: mismatched in position and wrapped in an organic covering, they possess a handcrafted, loose, or spontaneous precariousness that both synthesizes the mystical intimacy within the organic intimacy, as if extracting a cube of polished metal from the liver, and conceals the supposed perfection within the precarious, which protects it by nullifying it (the work PIECE, a circle covered in stitched fabric, also has a similar approach). THE WAY HOME is also a Platonic language, for which all knowledge was once a memory that would return us to the metaphysical home where we lived before birth. It could also allude to the story of the three little pigs forced to change their home by the breath of a predator. Almost all the works, in fact, allude to the theme of storage, or transportation. In addition to the enveloped boxes already mentioned, there is the innocent backpack of (HOW) WE LOCKED OURSELVES OUT OF OUR MINDS, the only explicit figuration in the exhibition, and the decadent and delayed movement of the bilious discharge of DELAY. Others, still, fold in on themselves, in this logic of the portable not entirely distinct from the structure of our organs, which gather their own expansiveness into the most compact form, encapsulating their grooves and creases, to then display, on the outer layer, an impeccable smoothness.

And if we were to cut through such smoothness, or even open our own epidermis, there we would see not the absolute inside, but a collection of new outsides, which would open to encounter other structures, always smaller, always external. In VAST AS PLEASURE, but especially in THE FLOOR WAS YOURS, there is an interesting exploration of the plastic possibilities of such a gesture, confusing inside and outside, or right and wrong, in structures contracted into a labyrinthine sinuosity, like a Klein bottle whose projective plane was improvised by an organism of involuntary intelligence. Also in the artisanal seams, in some of the accentuated works, the motif of the scar is suggested, nothing more than the stitched outcropping of the inner flesh over the outer skin.

Diseases are even more repugnant blooms. Their unfamiliar haunting doesn't exclude the supernatural, as they are the ultimate externality sprouting from within, corroding the lustrous mechanics of healthy organs into a gray spontaneity. For if the young body is like a machine, disease is its unforeseen event, an expressive outburst that undermines it, even in a gesture conducive to gluttony in its most morbid state, as in the induced pathology of foie gras or the decay of fungal cheeses. If the healthy liver was once a source of cosmic divination, could our desire to sicken it for the sake of taste be a sign of our current hedonism? Transforming the useful into the vitally superfluous is one of the alchemies of art, turning us all into aesthetes drawn to the repulsive plasticity of a well-crafted disease, just as gastronomy exceeds nutrition in gluttony, offering us the gift of fat, the ultimate symbol of human dominion over the environment. Wouldn’t all art be an existential fat?

Besides the three little pigs, we could also recall the story of Hansel and Gretel, in the candy house that fattens the meat of children destined for the old cannibal's oven. Fairy tales, fantastical and absurd, not only neglect the principles of literary realism, which preserve the verisimilitude of causes and effects, but also encourage a suspension of immediate meaning—instead of plausible logic, they prefer the impact of images, the drama of situations, and symbolic suggestion. These preferences are maintained here, both preserving the strangeness of the original story and expanding our relationship with the works. This is because the visual arts are not temporal manifestations, like literature or music, but spatial: they are organized in space and present themselves to the viewer in immediate simultaneity. Organized in this way, the works relate to the story autonomously, and not as mere illustrations. They are yet another collection of images and sensations that, by disregarding the narrative sequence that grants each object a specific weight, amplify their resonance. In this sense, the choice of the white cube is understandable, distancing the works from external circumstances, even if the cracking sounds emitted with each step remind us of the concreteness of the body, also forcing us into the role of the wolf, whose silence aims to surprise the three little pigs.

Another aspect of the unease present in fairy tales stems from their link between innocence and terror, as if they were stories manifested by the psyche of a wise infant still ignorant of the weight of violence, inserting it into the most unusual settings, thus highlighting it. Certain portraits of Francis Bacon are also similar, writes John Berger, who relates them to old Walt Disney animations: in both, the characters' naiveté does not mitigate the violence that deforms them, but rather accentuates the hostility of the act. In the works of Bartolomeu Santos, there is also a certain candor and lightness that ends up deepening their alien hostility. Their glassy look, although adding to their delicacy, when combined with such tortured anatomies and visceral flourishes, confers a disconcerting cynicism.

The exhibition THREE LITTLE PIGS, AND EVERYBODY ELSE, by Bartolomeu Santos with text by Rui Gueifão, is on display at Espaço Cultura das Mercês until October 15th.

BIOGRAPHY

Tomas Camillis is an author and researcher based in Lisbon, working on fiction and on essays in the interplay between art, philosophy and literature. He has a master's degree in Art Theory by PUC-RJ. In recent years he has participated in researches, taught courses in cultural institutes, helped organize conferences and published in specialized magazines. He currently collaborates with the MAC/CCB Educational Service and Umbigo magazine.

ADVERTISING

Previous

agenda

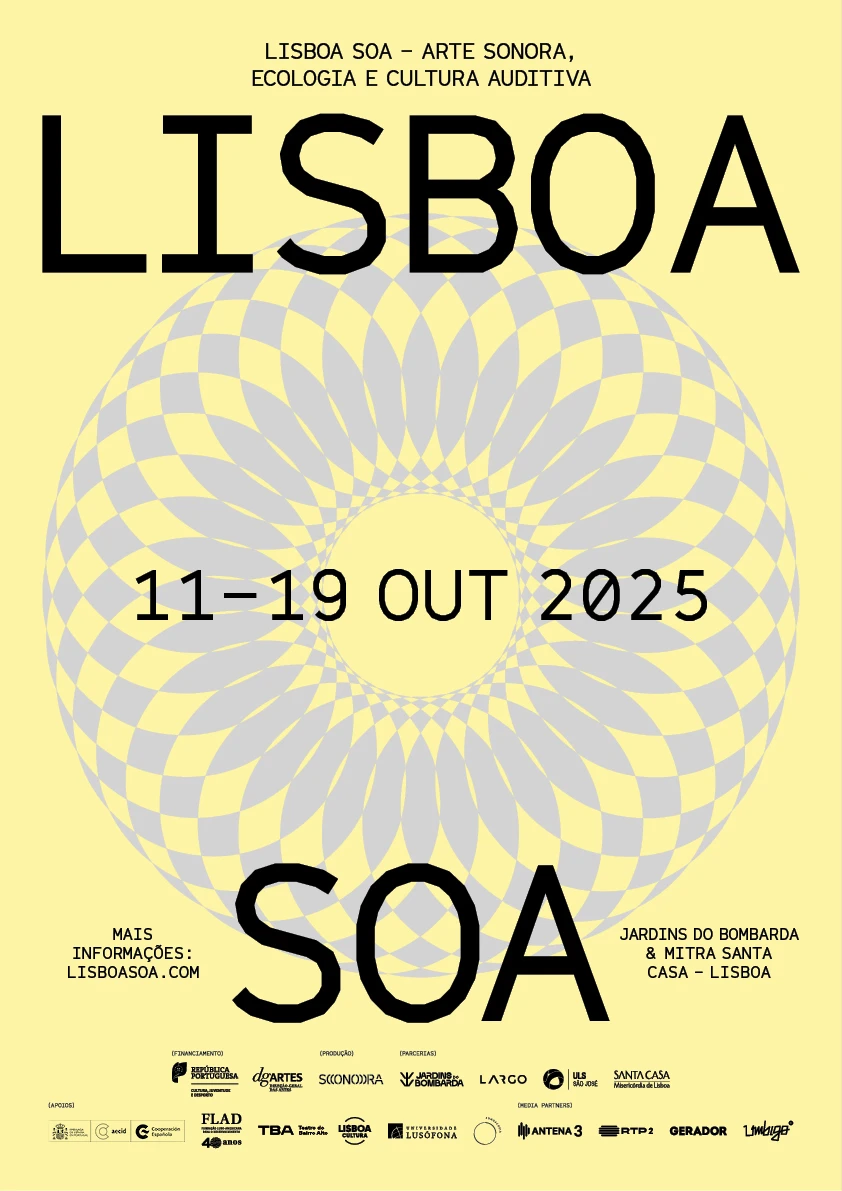

10 Oct 2025

Lisboa Soa 2025 kicks off this Saturday with nine days dedicated to the sound and listening of the city

By Umbigo

Next

article

14 Oct 2025

A Syllabary to Reconstruct II, at MACE

By José Pardal Pina

Related Posts

[A] Guilherme Parente, [L] FCC-bj2nj.jpg)