article

La Vie en Close: Manuel Costa Cabral at Brotéria

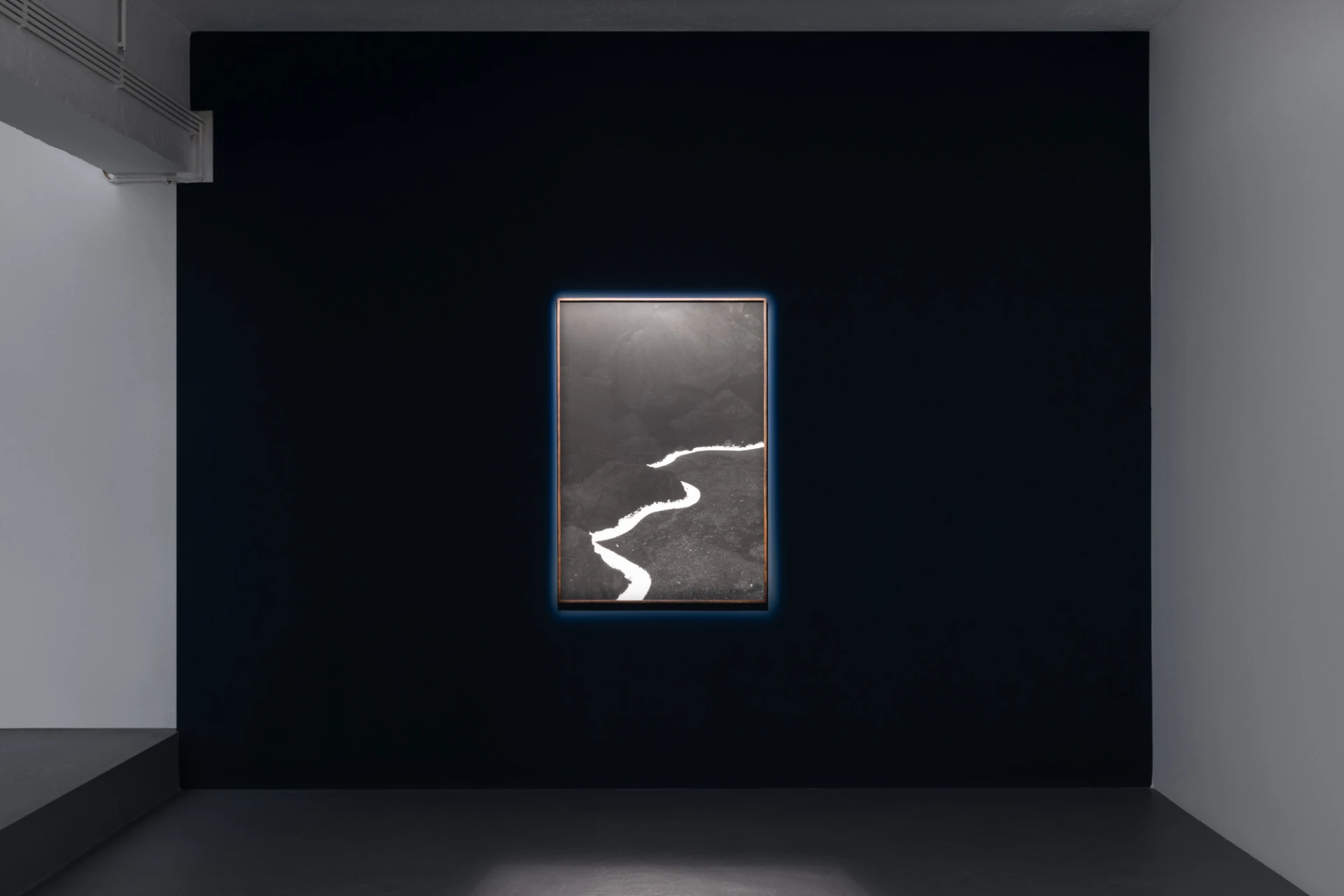

The exhibition Como um Certo Espelhamento, on display at Brotéria, revisits works by Manuel Costa Cabral from the 1960s to the present day. It covers a period of 65 years and is striking for its preserved lightness, which reconciles innocence with a playful quality, creating an experience of reality as an enchanting and bewitching mystery.

There are various colors, which most often follow the principle of tonal gradation. The shapes seem to obey a principle of folding: they are paintings like flattened origami, canvases that recall simple materials, straightforward shapes, and foldable paper. They are boyish message canvases. A boy who went out to see the world and came back without forgetting the first shapes he had seen, the first windows from which he felt the desire to go out and see outside. Costa Cabral's painting seems to attribute to any identifiable figuration—a face, for example—the condition of an unsolvable mystery; as if abstract forms ultimately had a greater connection with the concrete things that—inevitably—motivated the artist to paint. The consensus that a face signifies at first glance thus constitutes a kind of giving up on the search for the perfect form, on the exact translation of a life, of life's experience, which may be only an instant. And the abstraction of the paintings symbolizes self-forgetfulness as a means of resistance. Consider a set of three paintings: a face looking down, a flower, and a striated pattern tapering towards the base of the canvas; all of them suggest, in their own way, an idea of exhaustion and loss. One might say they are sketches of still lives. However, other paintings, from which no consensual forms can be extracted, have the power of dramas to be composed, to be personified, or which, at least, constitute an appeal to our living memory: then we remember sensations, we confuse them with the reality of the exhibition before us. We are no longer bound to a territory, a name, a face that vetoes the recreation of skins on which art essentially thrives. A face is, therefore, a dead flower, dripping with water—either too much or too little—from a striped fan towards the outside of the canvas.

Paulo Leminski, Brazilian poet and inventor, in his 1991 book with the beautiful title La Vie en Close, talks about stupor as a creative force, a word that gives its title to a poem, which reads as follows: “this sudden lack/ this stupid desire/ that leads me to doubt/ when I should believe// this feeling of falling/ when there is nowhere/ to go// this taking or leaving/ this vulgar poetry/ that does not allow lying.” Manuel Costa Cabral's painting serves as the stunned amazement of someone who, in order not to stay in one place, invented other worlds in depth where he could fall. Perhaps that is precisely what a good artist is: rushing to a place that does not exist, just to feel the weight of one's own body traveling through other altitudes, touching other vegetation, rejecting what one has learned as grammar, refusing the mirror, suggesting a certain mirroring.

The exhibition is on display at Brotéria until 11 January.

BIOGRAPHY

Master's degree in Portuguese Studies from Universidade Nova de Lisboa, with a thesis on Nuno Bragança. She is currently writing a doctoral thesis on Agustina Bessa-Luís and Manoel de Oliveira and melancholy. FCT scholarship holder, she has contributed to anthologies and has published poetry and essays in national and international magazines. She has published two books of poetry: “E o Coração de Soslaio a Todo o Custo” (2025) and “Penhasco” (2025). She is co-editor of Lote magazine. She writes literary criticism for the Observador newspaper.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

05 Jan 2026

Dois Stereos, by João Pimenta Gomes

By Mariana Machado

Next

article

06 Jan 2026

The Intersection of Individual and Collective Resistance: Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go

By Ayşenur Tanrıverdi

Related Posts

-rwdro.jpg)