article

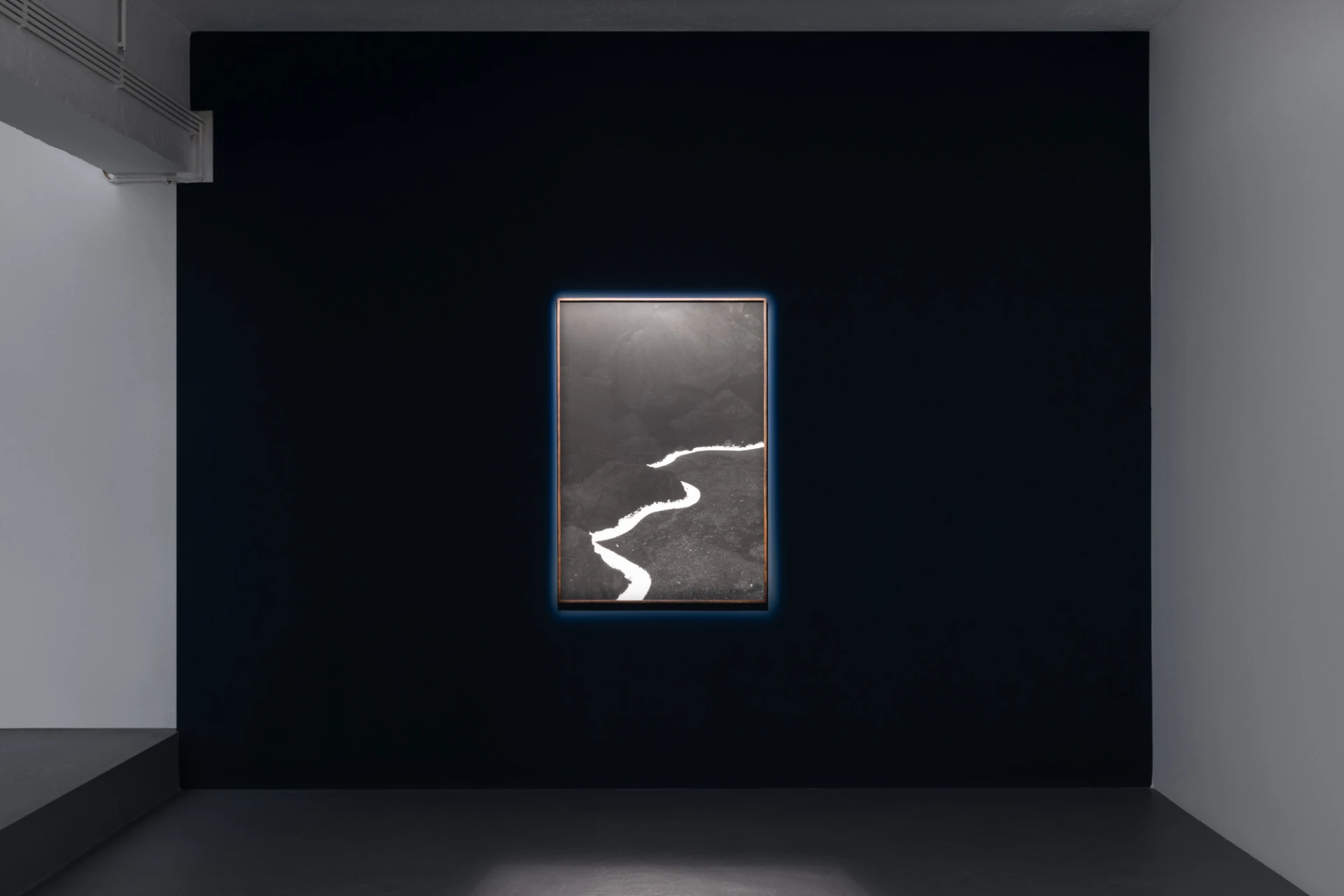

Selva Oscura, by Tito Mouraz, at 3+1 Arte Contemporânea

Ultimately, black is the most generous color. It is in darkness that the possibility of reading resides. To know how to see is to know how to walk in the dark: this seems to be the motto of Selva Oscura, by Tito Mouraz. And to photograph: to respect the opacity of bodies; in their covering to see the justice of things that are not fully revealed, and to condemn the stripping away of the mystery of the images seen, after all, bodies-always-to-be-touched.

If we consider the beginning and end of the exhibition, the journey is a return to the darkroom, metonymically and symbolically the place where the images are revealed. Thus, the light, disseminated by the white walls where the eight photographs are displayed on the upper floor of the gallery, composes the vestige of darkness, upon which the last photograph is seen, in the basement. The metaphor of the descent into hell, conveyed by the quotation from Dante—from which the photographer takes the title of the exhibition—is ritualized by the descent of the stairs. Light is, in effect, the translating residue of black, which in turn indicates the last road of the journey (/visit to the exhibition) and the first dwelling place of a panoramic sense of this photographic collection, through access to the basement that closes the exhibition. It is in the descent into a luminous darkness that the exhibition gains a face, an expressiveness, a tone. That is, the possible recognition of a message begins at the end. The end returns to the “mezzo del cammin di nostra vita”. Dante's Inferno appears as a calendar for our time, a frame for the moments whose record we are excluded from, in the form of desire and the temptation to inscribe and preserve the passing instants through which we gain memory. And isn't photography already a form of memory, of telling ourselves that we are an integral part of a configuration that has passed, sudden in its singularity? We pass, therefore, with what we see. We are kidnapped by the things we look at. Sudden passion of the gaze turned into lasting love, if, as Lacan wrote, love is giving what one does not have to someone who does not want it.

Handrails, barriers, tape, paint, posts, sidewalks, grass, cement, bricks, metal, nails, rock, tar, sky or smoke—more than sky and smoke, for the limits, the skies, of these photographs are formless like smoke—are the figurative elements of the nine photographs presented. They seem, more than figurative elements, to be means of signaling something whose figuration is projected. It is not clear whether we are situated in the instant following the birth and witnessing of a form, or in the moment preceding it. But everything perils in a curve, in a dilemmatic intersection of meaning. Hence, perhaps, the diary-like character pointed out in the beautiful exhibition leaflet signed by Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida and Humberto Brito. What is a diary if not an album of indecisions, a writing that inscribes surprise as a deferred state of reality? The idea that we cannot live except one step behind or one step ahead of the present that frames us, ultimately living empowered to witness ourselves, the capacity to look at ourselves, and to see ourselves looking? Selva Oscura is, therefore, and quoting from the program notes, "a series of breaks, false starts, dead ends, aporias."

Light and darkness cannot be differentiated by a greater or lesser disposition for vision. The idea that light is what allows us to see is deconstructed. Light illuminates precisely because, devoid of shadow, that is, of contrast, it dazzles. And, if vision depends on contrast, the truth is that Tito Mouraz seems to be defending darkness here as the guardian of some truth, or rather, of secrecy as the only possible truth: perhaps all that can be seen are shadows, in a confusion of scales, to which, incidentally, all the photographs contribute, except for two—one showing the edge of a road and a door, and another the edge of a road and a post surrounded by weeds. Apart from these two photographs, the others make it impossible to identify the dimensions of the elements that compose them. The difficulty in perceiving the size of the forms inscribes an experimental character in this exhibition, which is, at the same time, a refined and perfect whole—in the complete solidity that characterizes it—a draft of itself, a rehearsal of a work of which only glimpses are seen, of which fireworks are expected. But this does not happen as a promise that the exhibition would be a disappointment; rather, it activates the desire to look, to let oneself be intoxicated in an archive that is foreseen to be endless, for there is no other way to live than to think without a concrete horizon. One lives and creates with the awareness of the end, but the engine of creation will be more than of a subdued belief in the infinite. Thus, this is an exhibition conceived as an integral part of an artist's diary, which is his own work unfolding before our eyes, a praise to the incompleteness of days and to the redimensioning that art always operates on what surrounds us. It is this inherent incompleteness of creation that can turn a map into a novel, a photograph into a compass, and light and shadow into ways of provisionally reconciling the stardust of which we are made. We are, therefore, the clear (stained? noisy?) version of a lost shadow. Selva Oscura is the path of the search for that ancient refuge, for that lofty cellar from which we all originate.

The exhibition, on view at 3+1 Arte Contemporânea, is open until January 17.

BIOGRAPHY

Master's degree in Portuguese Studies from Universidade Nova de Lisboa, with a thesis on Nuno Bragança. She is currently writing a doctoral thesis on Agustina Bessa-Luís and Manoel de Oliveira and melancholy. FCT scholarship holder, she has contributed to anthologies and has published poetry and essays in national and international magazines. She has published two books of poetry: “E o Coração de Soslaio a Todo o Custo” (2025) and “Penhasco” (2025). She is co-editor of Lote magazine. She writes literary criticism for the Observador newspaper.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

06 Jan 2026

The Intersection of Individual and Collective Resistance: Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go

By Ayşenur Tanrıverdi

Next

article

07 Jan 2026

A Morte Escreve a Floresta, by Nuno Henrique

By Débora Valeixo Rana

Related Posts

-rwdro.jpg)