article

ÔNFALO: The Question of Everything

The day I visited the Ônfalo exhibition, Borges’s The Garden of Forking Paths lay in my bag. In moments like this, my instincts rarely let me down. After leaving Brotéria, I settled on a bench at the Miradouro de São Pedro de Alcântara and opened the book.

In the epilogue, André Maurois explained that Borges, in weaving his magical labyrinths, followed the path of the great Renaissance philosopher Giordano Bruno, who imagined an infinite universe without a center. The mythical narratives captured through Hugo de Almeida Pinho’s analog camera, aching to reveal themselves, resonated with Bruno’s ideas against a closed cosmos. I was so pleased to find them in the book immediately after visiting the exhibition.

Ônfalo opens a path to one of history’s most enduring questions: The Center. And the center, by its nature, implies cyclicality. Nietzsche describes this notion as the Eternal Return: the perpetual recurrence through which life reveals its circular structure. Every individual history (or the history of the world) is continually reenacted within each moment, entirely contained and reimagined in the ever-turning cycle of being.

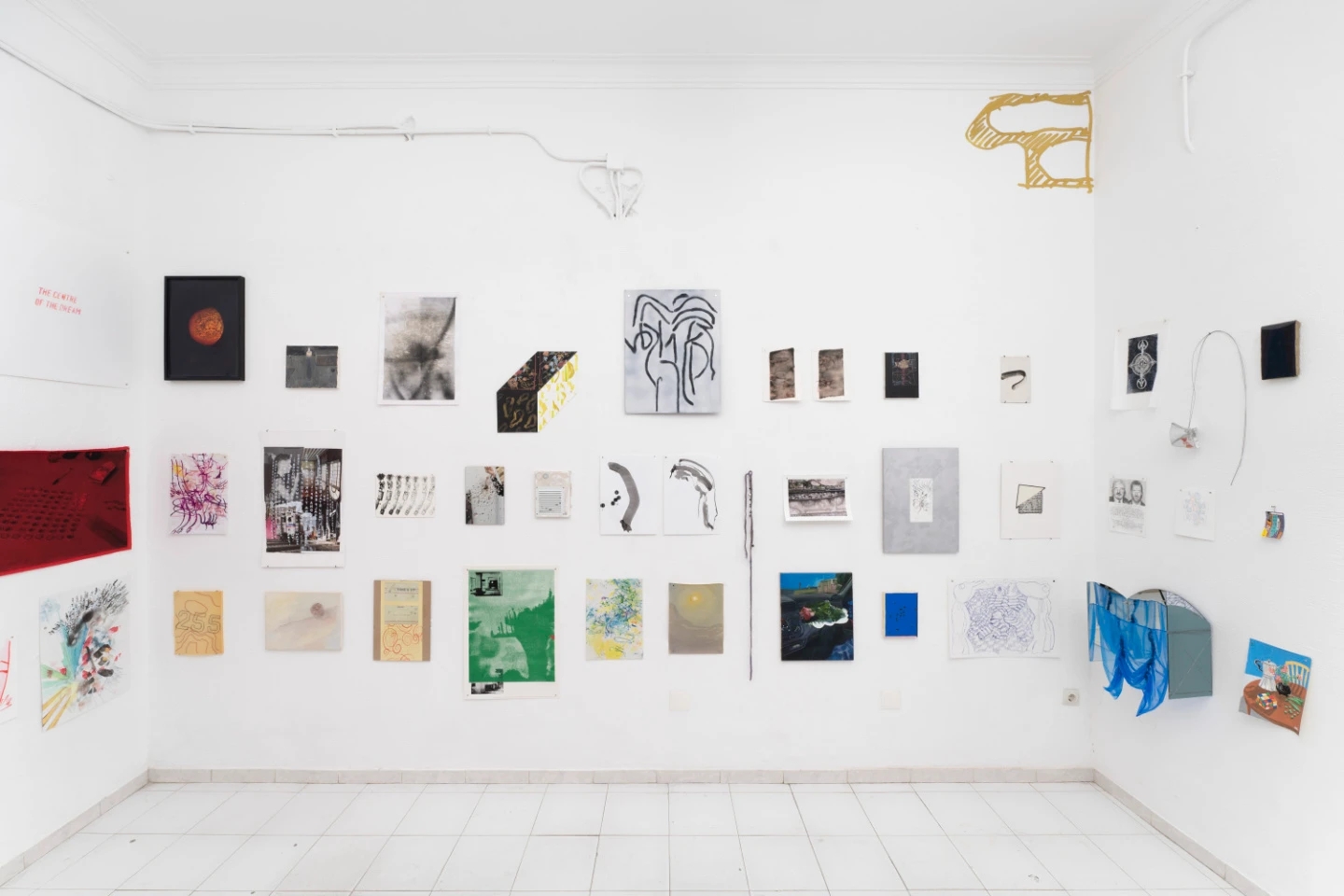

From the beginning, we sense that something is different. The exhibition door at Brotéria, the one we are used to seeing wide open, is closed.

Above it hangs a painting, precariously placed at an asymmetric angle. Not only does it refuse to stand “straight” from any viewpoint, but the image within it is also distorted. Looking closer, we recognize the photograph as depicting the Group of Aphrodite, Pan and Eros, the sculpture in Athens that shows Pan attempting to seduce the goddess of love and desire, Aphrodite. A projection of Pan, his veins pronounced, his animal nature unsettlingly magnified.

Here, form is prioritized over content. The distortion (or more precisely, the negation) of the center sparks the viewer’s curiosity. In other words, the center has lost its “centrality.”

Instead of entering through the main door, we turn toward the smaller entrance just to the left of Brotéria’s grand staircase. The first narrative that greets us there is that of Chance.

Here, within a small mound of sand, lie fragments of bone. Slightly cubic in form, these bones were once used in ancient divinatory dice games to foresee the future. The artist has recreated the Talus bones, taken from the area between the foot and the ankle, at a true-to-life scale in ceramics.

Hugo de Almeida Pinho ascribes a sense of chance to centrality itself. There is one thing on which we can all agree: movement begins at the center. Power, and our position in the world, rest upon the accident of the center.

The game of dice is a gesture of peculiar humor by the artist; after all, humankind can endure much - earthquakes, ruins, death, and suffering - but before chance, we are powerless. We must accept the dice as they fall.

Guided by the word Ônfalo (omphalos, ὀμφαλός), Greek for “navel”, the artist takes us to Delphi, at the foot of Mount Parnassus, once believed to be the center of the world. Among the passing images on the large main screen, we see Robert Fludd’s Utriusque cosmi maioris (1617). I find this symbol fascinating: a single string stretched and tuned by a hand reaching from above - presumably the hand of God - illustrating the idea that all beings, from the divine to the material, vibrate in cosmic harmony. It is a vision that perfectly intertwines with the concept of Ônfalo: the universe imagined as an instrument, where God’s order of notes sustains balance and symmetry across existence.

Found in Portugal’s Serra da Freita, the Pedras Parideiras, a rare geological phenomenon, carry within them a sense of fertility, as if “born” from the “mother-stone.” A small, elliptical biotite stone, astonishingly radiant, rests atop an earthen rise in the corner of the exhibition space, like a piece of science fiction plucked straight from a Stanisław Lem novel. Its shimmer is truly surprising.

The series of photographs is composed by overlapping two images: in the background are photographs taken in the Grutas de Mira de Aire in Portugal, and overlaid on them are archival images from different contexts, ranging from the 16th to the 21st century. One detail that caught my attention most is John Collier’s small-scale 1891 painting, Priestess in Delphi. The painting depicts Pythia, the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo in ancient Greece, holding a laurel leaf and inhaling a heady vapor rising from a chasm in the earth, known as pneuma, as she enters a trance-like state to deliver her prophecies and foresee the future. And in fact, Pythia herself becomes a center: the center of prophecy.

Another symbol I consider important is Benjamin Franklin’s 1754 cartoon Join or Die, one of history’s most famous political illustrations, which can also be read as a reference to the problem of centralization. With this drawing, Franklin argued that the British American colonies needed to unite against the French and Native Americans. Each segment of the snake represents a colony, disconnected from the others. The image symbolizes geographical fragmentation and political division, and, at the same time, reflects a desire for centralization, a will to consolidate power. In essence, it is a “battle for centrality.”

In the final small room of the exhibition, we encounter the rawest narrative. Here, there are no symbols or associations, only a single slide projection displaying a 35mm photograph of a freshly painted wall inside the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome. The image depicts a nativity scene and one of the oldest known Marian paintings, highlighting the importance of the female figure and the idea of nativity as the center of the world, inviting the viewer to silence.

Ônfalo is woven with convex and concave structures. In the convex forms, we encounter the earth’s potential fertility, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and human-engineered drilling tunnels located 12,000 meters below the ground; in the concave, we explore the aphrodisiacal effects of pneuma, caves, and hidden refuges. And in this, we realize that the joyful moment when Hugo noticed a smiling face within a stone in the Corycian Cave may hold the center of everything, much like Borges’ branching paths, where each choice opens an individual center of its own.

The exhibition remains on view until November 8 at Brotéria Gallery.

BIOGRAPHY

Ayşenur Tanrıverdi is an Istanbul-based writer, living in Lisbon since September 2022. She studied at Istanbul University and is the author of two published works of literary fiction. A regular contributor to Cumhuriyet, a major Turkish newspaper, where she focuses on Portuguese culture. Her essays and critical texts on theatre, literature, and contemporary art have also been featured in various art magazines.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

23 Oct 2025

Museu Zer0 – Opening

By Ana Isabel Soares

Next

agenda

24 Oct 2025

Artissima 2025 starts on October 31st in Turin

By Umbigo

Related Posts