article

Second Skins, Hybrid bodies: Alexandra Bircken at Culturgest

“The works presented at Culturgest, previously shown at Kunsthaus Biel in Switzerland, emerge from the conjunction of disparate elements, where heterogeneous materials generate forms that suggest bodies or bodily fragments analogous to human anatomy. Bircken emphasizes how machines themselves are hybrid entities: their internal structures of cables and engine components evoke human organs, arteries, and muscular fibers. This wide range of materials highlights the boundary between humans and their constructed environments.”

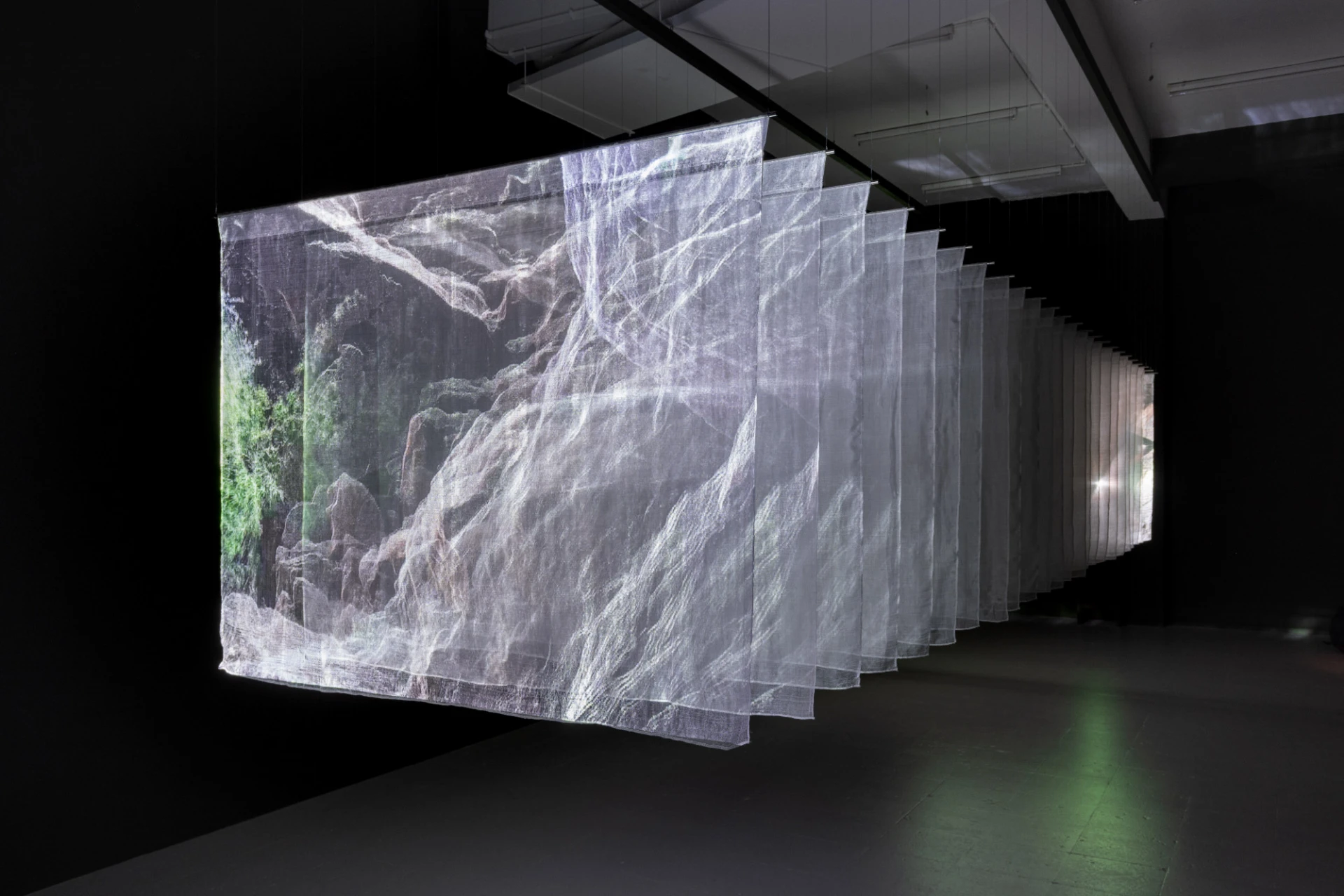

Walking alone through the rooms of Culturgest on a Tuesday morning, observing the striking constellation of sculptural bodies by Alexandra Bircken (1967, Cologne) brought together in the exhibition SomaSemaSoma, curated by Bruno Marchand and Selma Meuli, I could not help but find myself plunged into a delicately violent convergence between the Ballardian universe of Crash (1973) and Julia Ducournau’s film Titane (2021). For those unfamiliar with these references, Ballard’s novel, later adapted into a film by David Cronenberg, follows a group of car-crash fetishists whose morbid fascination with automobile accidents revolves around death, bodily deformation and mutilation, and the fusion of technology and flesh, metal and sex. Central to the narrative are two protagonists whose involvement in car crashes radically alters their perception of people, objects, and desire.Titane, by contrast, tells the story of Alexia, marked by a childhood car accident that results in a titanium plate being inserted into her skull. This traumatic event triggers a visceral attraction to machines, leading her to work as a dancer at car shows and ultimately to engage in a sexual encounter with a car, from which she becomes pregnant. At the same time, she is consumed by repressed rage and love, forces that gradually transform her into something radically hybrid.

The works presented at Culturgest, previously shown at Kunsthaus Biel in Switzerland, emerge from the conjunction of disparate elements, where heterogeneous materials generate forms that suggest bodies or bodily fragments analogous to human anatomy. Bircken emphasizes how machines themselves are hybrid entities: their internal structures of cables and engine components evoke human organs, arteries, and muscular fibers. This wide range of materials highlights the boundary between humans and their constructed environments. At the same time, the “nervous system” of machines, their cables, mirrors the human one.

Many of Bircken’s “bodies” are therefore open, dismantled, exposing their interiors. What emerges is not a simple dialogue between humans and machines. As in Ballard’s Crash, the machine penetrates, both formally and metaphorically, the imaginary, eroticizing wounds and imposing a new model of corporeality. The body becomes a new surface for inscription, a traumatic script written on the skin that redefines subjectivity; the protagonist is no longer the same after impact. Bircken’s bodies, particularly the opened motorcycles, cable harnesses, and fuel tanks, reveal this structure as a surgical incision, where technology functions as a second epidermis.

In Ducournau’s film, the protagonist’s body undergoes a violent metamorphosis in which metal is no longer an armor or prosthesis, but a biological destiny, turning the body into the site of radical hybridization. Similarly, the bodies, or rather, the bodily shells, constructed by Alexandra Bircken are hybrid entities. It is worth noting that Bircken originally trained in fashion, a discipline concerned with garments and shells designed to contain and shape the human body. Her dissected, almost cyborg-like robotic figures, resembling imperfect Terminator bodies, bring to the surface a tension between power and vulnerability. Like Titane, they compel us to reflect on contemporary figures of the Übermensch that surround us today, endlessly reproduced and circulated.

In SomaSemaSoma, the body becomes a site of continuous negotiation: exposed, vulnerable, and endlessly rewritable. Bircken does not celebrate hybridity; she dissects it, revealing its constant tension between control and surrender. As in Ballard’s novel and Ducournau’s film, technology and engines are not external forces, but elements already embedded within us, amplifying our weaknesses as well as our fantasies of power, without saving or destroying us. In doing so, Bircken exposes the contemporary Übermensch as an unstable construct, assembled from precarious prostheses often concealed beneath delusions of omnipotence.

The exhibition is open until February 1.

BIOGRAPHY

Orsola Vannocci Bonsi is a cultural producer and advisor who has called Lisbon home for eight years. Through her work, she fosters connections through her research and the projects she helps bring to life. With experience as a sales director and gallery manager in various Portuguese art galleries, she was also project manager and artistic director of FEA Lisboa, founded the curatorial collective Da Luz Collective, and contributed to the programming of festivals in Italy and Portugal.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

14 Jan 2026

PICKPOCKET, at the Balcony Gallery

By Tomás Saraiva

Next

article

15 Jan 2026

complexo brasil, at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation

By Ana Grebler

Related Posts

[A] Alexandra Bircken, [L] Culturgest-lehev.jpeg)

©photoElaBialkowskaOKNOstudio-7yoip.jpg)