article

Trunfo ou Triunfo: A Deconstructive Approach to the Concept of Power

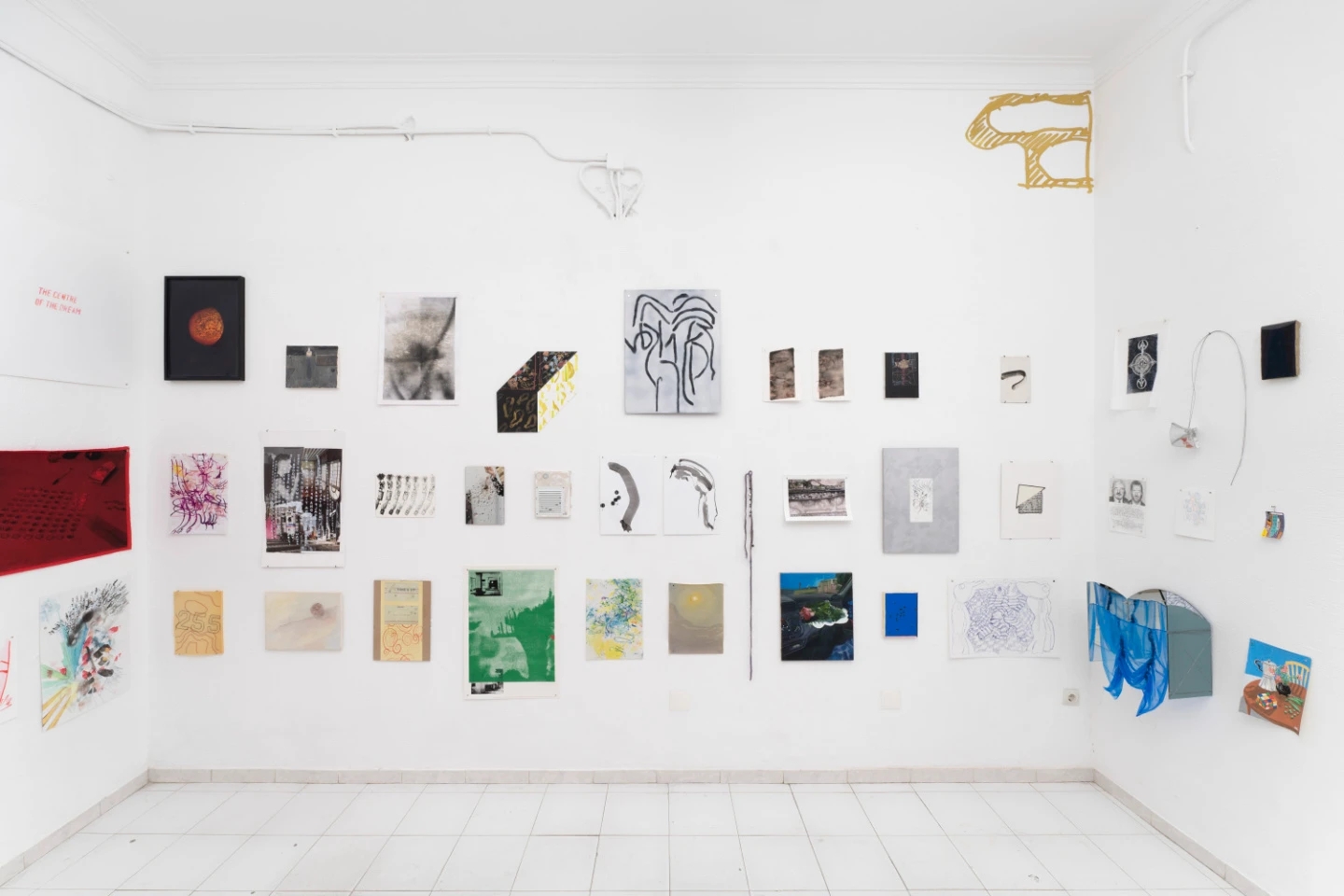

Ana Fonseca’s exhibition Trump or Triumph, shown at OSTRA practice, examines discursive practices that put thought to a game of truth, transforming it into an object of reflection - whether moral, scientific, or politica

We are confronted with two phonetically resonant words, Trump and Triumph, both of which derive from the Latin triumphus and, through centuries of shifting contexts, have come to embody a kind of internal opposition, standing today as representatives of a paradox born from their shared origin.

Today, the word Trump carries multiple unsavory meanings, having become a “brand” often evoking the enforcement power of large states. And I suppose the same dark silhouette appears before all our eyes, but for now, let's set this image aside.

The word Trump appears among the card games listed by Rabelais in his 1534 Gargantua. From the sixteenth century onward, across European cultural centers such as France and Austria -particularly Vienna- the terminology of card games evolved within leisure practices favored by the upper-class intelligentsia. This semantic drift continued into the nineteenth century, during which trump came to denote both a figure endowed with superior qualities and the act of “calling for trumps”, that is, summoning the trump suit in partnership.

Finding a reference to Rabelais in Ana Fonseca’s work feels like a fortunate coincidence, because Rabelais is a foundational figure of humor and satire in literature. Fonseca’s practice similarly unfolds through the layered expansion of witty inventions, emerging organically through her intelligent playfulness. Her artistic language draws strength from historical thought without relying on it, foregrounding humor that invites both delight and reflection.

Recalling several of the artist’s earlier exhibitions - Put Your Thinking Hat On, Alegoria do Valor e do Merecimento, or Master Baker - it becomes clear that humor in her work is not a material added to art but a natural extension of it. Within this altered world, where the artist freely projects her own singular character, Fonseca plays with both the form and content of objects, adding new layers of illusion to an already illusion-filled reality. The effect is simply dizzying.

By the late fourteenth century, the word triumph had come to mean success in battle. In Roman antiquity, it referred to the ceremonial processions held to celebrate military victories. In the modern world, however, some forms of triumph no longer have a living counterpart; certain words have fallen into obsolescence, emptied of their original force. Much like horses, whose role has been reduced to entertaining the wealthy, these are words that belong to another era, stranded in a time no longer their own.

The concept of “game”, in its simplest terms, is a space where ostentatious seriousness, dogmatic order, and all bewildering emotions are enacted on the plane of amusement and laughter. And yet, it can be perilously unpredictable. Trump and Triumph function both as themes and as instruments of reasoning. The viewer must sense the fine line between game and our ordinary nature for truth to be fully revealed. In the game, we oscillate between concealing our emotions and ambitions and being consumed by them. This echoes Spinoza’s counsel for attaining truth: set aside grief, laughter, and excitement: make your move.

One of the defining features of Ana Fonseca’s engagement with the world is the multiplicity of meaning she derives from her relationship with materials. This lends her artistic approach a depth that is candid, direct, ironic, celebratory, subversive, and exalting all at once. Here, the question Fonseca poses at the outset is crucial:

Can there be a trump without a counterpart?

Does the notion of “triumph” hold any significance within a democracy?

Today, we find ourselves reflecting on the concepts of power and authority more than ever, for we are directly affected by events. Political forces seem to breathe down our necks, and wars and destruction are no longer distant phenomena, they are right beside us, visibly and unavoidably.

In Subject and Power, Foucault examines the concept of “biopower.” He designates this emerging form of authority as biopower, a disciplinary power that approaches the human body as a machine. Law begins to function more like a norm, and the legal system becomes part of a broader apparatus aimed at regulating the forces of life. In short, biopower, with its focus on life itself, produces a society of normalization: a society that compels individuals to conform, rendering them “normal.” It imposes truths upon them regarding themselves, enabling power to envelop the body without resorting to violence, making it compliant and docile. In this sense, Ana Fonseca opens a fertile space for reflecting on the semantics of power.

The exhibition defines its own architectural boundaries through angular symmetries and a kind of circularity. The circular dimension of the card game atop the antique, classically styled wooden table finds its echo in the drawing on the canvas. Around the table there are no chairs, no call to play, yet still seems to expect our presence. The gap opened between the game and the player becomes the void of the space of inquiry. Ana Fonseca makes the presence of the chairs in the room felt through their absence.

The artist engages with the concepts of soft power and hard power, introduced by American political scientist Joseph Nye, presenting them as possible modes of operation for authority. Ana Fonseca’s sensitivity to drawing, guided by her principle that “Everything starts with a question to be thought through drawing” renders these notions with remarkable subtlety. The inclusion of a hand grenade alongside elegant objects in the same frame is striking; figures at their peak simultaneously “point” to below. Their facial expressions have either been demonized or their bodily contours erased. I am reminded of Anton Chekhov’s principle regarding story structure: if a rifle hangs on the wall at the beginning of a tale, it must fire by the end. The objects in the painting carry an uncanny potential, and as viewers, we take pleasure in this tension.

The philosophy underpinning the artist’s work is built on destruction, purification, and reasoning, and for precisely this reason, it is highly susceptible to fragmentation. The exhibition opens a space rich in textual and symbolic context, where meaning is constantly deferred, in line with Derrida’s principle that there is nothing outside the text.

Ana Fonseca first brings binary oppositions together, then dismantles them and generating fresh meanings. In today’s world, where ethical approaches in politics are eroded, such inquiries are more vital than ever.

Trump or Triumph can be visited at OSTRA practice until February 14.

BIOGRAPHY

Ayşenur Tanrıverdi is an Istanbul-based writer, living in Lisbon since September 2022. She studied at Istanbul University and is the author of two published works of literary fiction. A regular contributor to Cumhuriyet, a major Turkish newspaper, where she focuses on Portuguese culture. Her essays and critical texts on theatre, literature, and contemporary art have also been featured in various art magazines.

ADVERTISING

Previous

agenda

05 Feb 2026

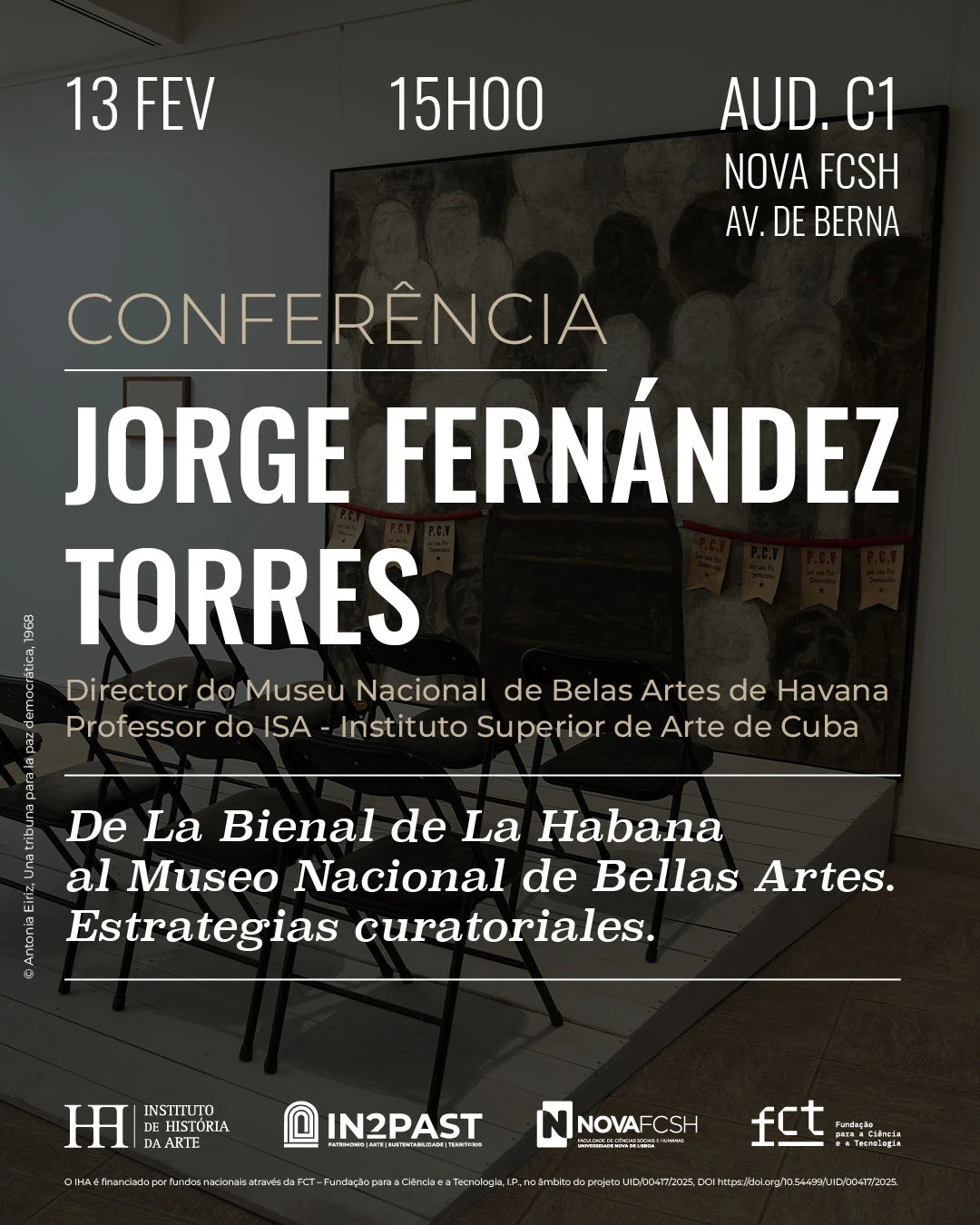

Conference with Jorge Fernández Torres: De La Bienal de La Habana al Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. Estrategias Curatoriales

By Umbigo

Next

article

06 Feb 2026

Traslados, by Marcelo Moscheta

By Débora Valeixo Rana

Related Posts