article

The passive spectator - Vieira da Silva: Painting in Motion

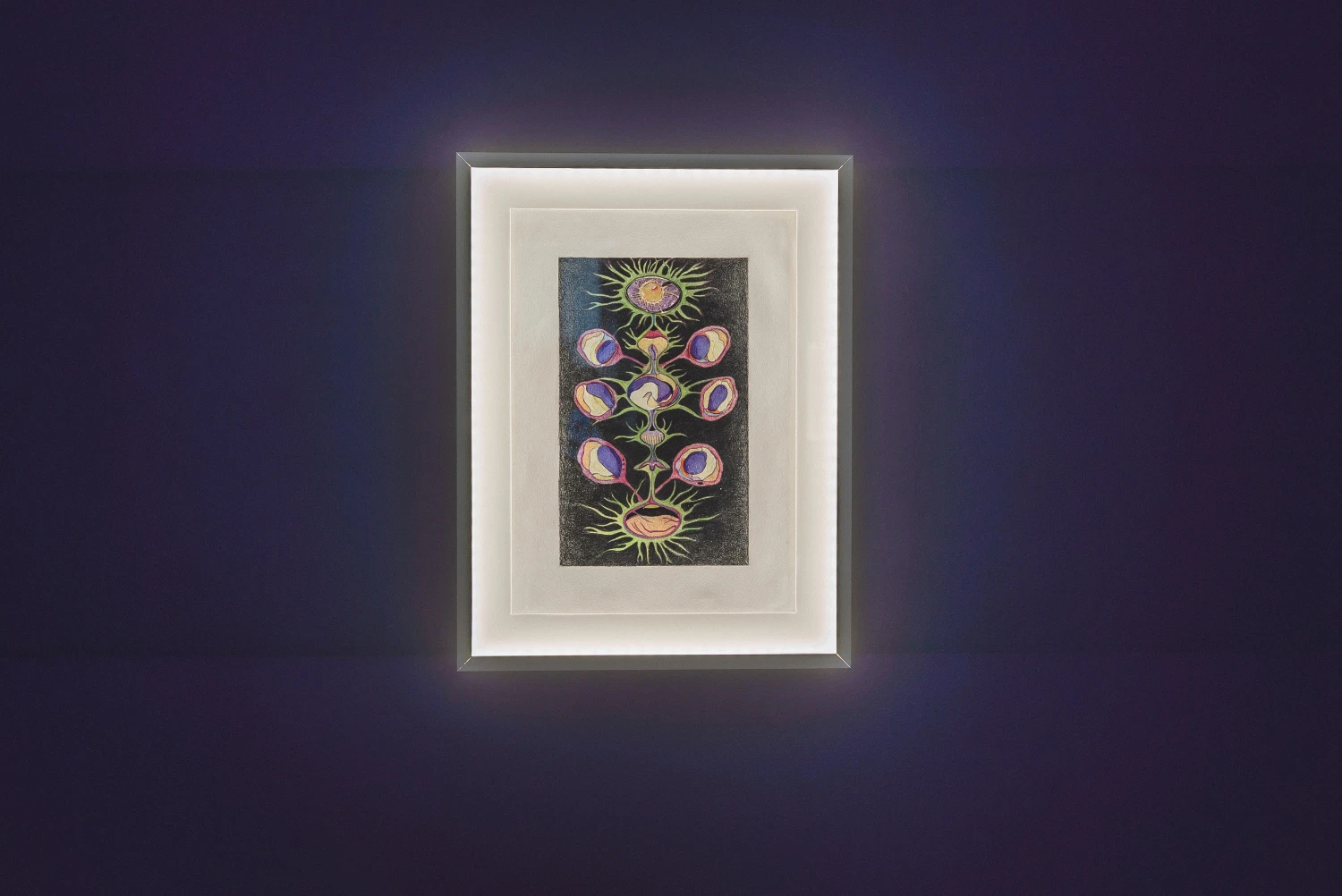

Vieira da Silva: Painting in Motion is the first immersive exhibition in Portugal dedicated to the work of a Portuguese artist. Musician and composer Rodrigo Leão created the original soundtrack especially for this animation of Maria Helena Vieira da Silva's painting.

If Western art embraces the stability of a Byzantine icon, which at the top of the church fits the dome to cast its eternal gaze upon our deviations, or of Jacques-Louis David's Marat, who died in the bathtub to awaken to eternity, imposing himself marble-like on the inconsistency of our memory, it is also the history of movement, more agile in modernity. For Mário Cesariny to be able to draw, jolted by the Lisbon tram, shaky silhouettes that comment on our incomplete mastery of circumstances, there were at least two things: (1) a Picasso in love with the linear conciseness of Altamira's paintings, who in a few quick gestures aimed to capture the essence of something, and (2) equine transport finally replaced by railways — although Erasmus wrote his Praise of Folly on horseback, it escapes me how the animal's cadence might have influenced his prose. Even earlier, Titian contrasted the ideal beauty of the Greek nude with the earthly nude, with countless reclining bodies, countering the touching innocence of the ancients with an eroticism that displayed its concreteness in chaise longues and beds. Later, it was Ingres who elongated the spine of his reclining Odalisque, thus confirming Hogarth's maxim: beauty would not be the stability of the parts in a cohesive whole, as predicted by the Greek canon, but the line that winds in hypnotic movement. In the 20th century, a young Duchamp, interested in synthesising futurist dynamism with cubist fragmentation, added to such critiques of stable beauty with his Nu Descendo uma Escada, a body now devoid of even anatomy, as it is merely the mapping of the succession of a movement. Also energetic were the oblique constructivists, admirers of machines as much as Henry Ford, who pasted on the walls of his factory some excerpts from Emerson on self-determination, the same thinker who influenced the poet Walt Whitman in his vision of a self in constant expansion with the world. I wonder if the ghastly ecstasy of the French revolutionaries was caused not only by the upheaval of social change, but also by the arcs of the heads rolling on the scaffold, as well as the cascades of flesh unfolding in the Rococo paintings, to which they were unaccustomed.

Where does this modern fascination with energy come from? Our phobia of fixity excludes from our beliefs any external design or transcendent determination — for constructivists to dismantle geometry into divergent sections, it was necessary to abdicate God and the monarchy, memory and astrology, destiny and the apocalypse. It was necessary for Descartes to doubt everything except himself, for Robespierre's emissaries to destroy the immense cross of gems and gold made by Abbot Suger and kept for almost half a millennium in the Abbey of St. Denis, for Darwin to profess a nature that is not the race of prior preference, but of adaptation, and for Einstein to tell us that everything moves in a universe without a centre, where each body affects the other. For the modern human is the self-determined individual for whom nothing is sacred or alien to his designs, whose greatest treasure is his own freedom to think and act — existence precedes essence, the existentialists tell us. And modern art is, even in its most stable examples, such as Mondrian's paintings, an attempt to activate the viewer, awakening their interest in acting in modernity.

Vieira da Silva's work contemplates both the logical impetus to structure the environment that once determined us and the expressive outbursts that impose themselves on our spirit and bathe us in disconcerting feelings when we are allowed the freedom to live authentically. In modernity, the individual is also his own biggest problem, because while on the one hand he is assured of his strength and lucidity, on the other, he uses them to recognise his own limitations and the enigmatic nature of his existence. These are the two forces that construct Vieira da Silva's paintings. His brilliance lies in not resolving contrasts, preferring instead to make them explicit in their tensions. He embraces everything, without reducing anything — rather than simplifying the exuberance of our experience, he structures its complexity.

The exhibition Vieira da Silva: Painting in Motion participates in this recent enthusiasm for the immersive experience, a residual activity of the acceleration of our daily lives. If modern art sought new forms that would activate the viewer's consciousness, such experiences use an imposition of visual and auditory stimuli to achieve the opposite — they think for us, outsourcing the experience. The exhibition imagined, for me, a supposed movement of the works of Vieira da Silva, an artist whose paintings aimed to stimulate autonomous mental movement. Even though it was an exhibition dedicated to childhood, it is as if it did not trust the quality of the original works enough, supposedly too serious for children's interests, preferring to appeal to visual artifices more palatable to an audience accustomed to the maximum convenience of all services. If good children's work is intended for the child in all of us, then adult work is also intended, perhaps, for the maturity present in children. It is important, when encouraging childlike wonder, not to feed adult laziness. Mass culture and propaganda, instead of activating us to develop, prefer to impose themselves on the passive viewer. They have therefore accustomed us to an assault of stimuli that reduce our sensitivity and attention, fostering a daily life determined by convenience. It is telling that the video in the exhibition is on a loop with no breaks — the imposition of stimuli binds us to endless entertainment.

Since the 1920s, countless works have explored film technology, such as Duchamp's Anémic Cinéma and Murphy and Léger's Ballet Mécanique. However, these works are authorial exercises, originating from within the characteristics of the genre, questioning its possibilities and awakening new mental regimes in the viewer, while the exhibition Pintura em Movimento (Painting in Motion) proposes, under the argument of promoting Vieira da Silva's work, to highlight elements of her paintings to arrange them in new compositions and rhythms, superimposing on them a temperament alien to the artist herself. As such, the exhibition neither provides a new understanding of her work nor stands as an authorial construction. ‘Because paintings are silent and static, the most obvious way to manipulate them is by using movement and sound,’ John Berger tells us. [1] Peter Greenaway makes a similar criticism of cinema as a whole, saying that filmmakers often limit themselves to filming literature, rather than rethinking the very concept of history through the possibilities of film — which is what video art sets out to do, in the words of Hans Richter: ‘I discovered that abstract form in film is not the same as in painting, where it is the ultimate expression of a long tradition, while film must be discovered in its own properties.’[2]

As early as the 19th century, various artists linked artistic practice to technological development in order to move away from what they understood to be the passive contemplation of museums in favour of useful art realised in furniture and utensils, domestic architecture and urban planning. The issue, however, is not about the differences between galleries and squares, industry and craftsmanship, contemplation and exercise, but above all about the need to branch out the artistic experience, which, when well constructed, is always a state of intimate activity — the distinction between a medieval illumination and a Bauhaus chair is that, it was assumed, the furniture would also nurture the body of the modern individual, for whom acting and thinking would be part of the same process. Art, therefore, does not provide us with an entertaining escape but rather a transformative encounter. The stillness of the paint on the canvas does not diminish, but rather accentuates the dynamism of certain works — it does not manifest, but rather suggests a movement that the viewer will articulate through their own possibilities, in turn also having their own cognition transformed by the impact of the perceived image. The work thus expands into the realm of the open regime, as it depends on the viewer. Such restrained dynamism has been explored by countless modern artists, such as Vieira da Silva, who were interested in the imaginative apprehension of human perception.

Movements such as the Bauhaus, for example, facilitated contact with art, but always through new works. They did not intend to multiply Rembrandt's paintings or Bernini's sculptures, but to construct other artistic models. For the simple technical reproduction of paintings, writes Walter Benjamin, removes the aura from the works. If, to experience a work, it was previously necessary to go to the place where it was inaugurated, now images of the works assault us at every moment and in every place, reducing them to mere objects manipulated without commitment to their integrity. The modern spirit, uncompromising towards anything that escapes human control, has ended up infantilising otherness. I wonder if the role of museums is not also to popularise the work without removing its reverence, making pilgrimage a recurring activity in the daily lives of their audience.

Vieira da Silva: Painting in Motion is the first immersive exhibition in Portugal dedicated to the work of a Portuguese artist. Musician and composer Rodrigo Leão created the original soundtrack, specially composed for this animation of Maria Helena Vieira da Silva's painting. The exhibition is on display at the Arpad Szenes—Vieira da Silva Foundation until 31 December.

[1] Berger, John. Ways of Seeing, ep. 1.

BIOGRAPHY

Tomas Camillis is an author and researcher based in Lisbon, working on fiction and on essays in the interplay between art, philosophy and literature. He has a master's degree in Art Theory by PUC-RJ. In recent years he has participated in researches, taught courses in cultural institutes, helped organize conferences and published in specialized magazines. He currently collaborates with the MAC/CCB Educational Service and Umbigo magazine.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

27 Nov 2025

About Cynara Complex: Diana Policarpo at VNBM Arte Contemporânea

By Daniel Madeira

Next

agenda

28 Nov 2025

3rd Edition of Centro Mutável, in Montemor-o-Novo

By Umbigo

Related Posts

[A] Guilherme Parente, [L] FCC-bj2nj.jpg)