article

The Branches of Life: Vivenciar at 3+1 Arte Contemporânea

The exhibition is a dialogue between Carneiro's illustrations and the works of Charlotte Moth, a British artist who assimilates all of this. It promotes the mythology of Carneiro, but through different formats, both allowing the viewer to experience the experience recounted in Carneiro's illustrations and reinforcing, through the play of reflections, this reality that is the intertwining of all things.

Creating is not imagination, it is taking the great risk of having reality.[1]

Clarice Lispector

In his work The White Goddess, Robert Graves writes that each letter of the ancient Irish Celtic alphabet corresponds to a tree sacred to the Druids. “The Druistic schools were founded in woods or groves, and a large part of their mysteries concerned branches of different types,”[2] particularly how they intertwined in the forest webs between the treetops. But Beth-Luis-Nion (Birch-Sorbus-Ash for its first three letters) represents not only a deep connection with nature but also their belief in the alliance between language and reality. For the Celts, it was through poetic testimony that reality would be revealed. Even “when armies fought, the poets on both sides would retreat to a hill to judiciously discuss the battle […] and the combatants would later accept their version of the event, if it was worthy of commemoration in a poem.” [3] Wittgenstein might have resisted supporting them. As a young man, he professed that language would only be true when elementary: a logical discourse to represent verifiable facts. Later, he reconsidered words not as mirrors, but as tools. Language would be a game of its own rules that does not reflect, but rather formulates, our conception of reality. But it was precisely the tenuous interstice between evidence and invention that the druids sought—when poets judged battles, they cultivated a lucid investigation of the essence that rose beneath the event, "refining a complex poetic truth into an exact attestation." [4]

One of Alberto Carneiro's illustrations featured in the Vivenciar exhibition presents a curious representation of the human: an enormous mirror and an eye staring wide-eyed at the landscape. Could his entire philosophy be condensed here? The artist doesn't invent—he contemplates the gentle wonder of nature, then reflects upon it. Thus, he composes the reality of human experience. A fundamental body renounces the superfluous to surrender to perception: sense and consciousness united in an art that is the attentive dialogue between subject and object. We absorb the world, nurture mental constructs, and weave them back into nature. But not to transcend it: to evoke its immanence, transforming it into itself, making it finally find itself.

Or perhaps there is no dialogue, something alien within us that resists nature, our intellect: a machine that imposes upon it the strange architectures of its rational order. In the other illustrations, tangles of geometric solids abound. Could these be the enchantment of rational reveries, the result of the sheer power of the independent human? Their intertwining in the landscapes, however, suggests precisely an interaction with the world—called Projecto para intervenção na paisagem (Project for Intervention in the Landscape), they are more than future sculptures: I see them as the cartography of a consciousness acting in the world. Their complexity hinders logical clarity. Also, in the bulk of our experience, we lack precise relationships of cause and effect—the three times, the intimate and the external, the intellect, feeling, and sensation: everything intertwines in the present moment.

It was on his childhood farm that Carneiro, a pioneer of Land Art, developed a practice that explored the individual because of their vital connection with the environment. His delicacy does not override reality—with it, he constructs meaning. In the interstice between everything, perhaps the complexity of our existence is elucidated. He therefore cherished the balance of gardens, situated between the uncontrolled woods and the seclusion of the tower, where humans dialogue with nature. In them, he sought balance between subject and object, composing works through subtle and systematic touches, adapting to the attributes of each thing, therein glimpsing the general rhythm of life. Perhaps he understood essence not as the perennial substance beyond experience, but as something formed by it, like someone who no longer swims against the current of a river, discovering it circular, devoid of a source. His harmony renounces classical beauty, an absolute construction of the intellect that imposes its preferences on the world. He preferred the honesty of things that, polished by the artist's hands, become precisely what they are—what they already were, latent. For the essence is perhaps not the impeccable composition, but rather the common pulse that gives birth to distinct phenomena: a well-viewed stone contains the whole world.

The exhibition is a dialogue between Carneiro's illustrations and the works of Charlotte Moth, a British artist who assimilates all of this. It promotes the mythology of Carneiro, but through different formats, both allowing the viewer to experience the experience recounted in Carneiro's illustrations and reinforcing, through the play of reflections, this reality that is the intertwining of all things. Its lucid subtlety demands no attention, as it does not invent for the sake of impact, operating within the existing to, without fanfare, reveal its gifts. I was reminded of the druids perhaps when seeing his photographs of intertwined branches, evoking an ancient thematic interest of Aries and, like him, glimpsing the tenuous natural structures.

And if each thing manifests the same rhythm in its own way, in other works this latent pulse is suggested in the relationship between certain objects that, at first glance, seem disparate: glass cylinders and twisted iron rods, fossils, lids, and geometric solids. Never organized by the norms of classical beauty, they are arranged in a harmony that respects a more malleable order, available perhaps not to the intellect, but to poetic intuition. We should not be suspicious of the presence of artificial things: since humans and the world are children of the same nature, the manufactured can be a sibling of the natural. It is also in what the hand constructs that the attentive spirit reveals the essence of nature. Perhaps this is why he opted for photographs, mirrors, and holograms, models that do not stray from reality because they relate to it inexpressively. But they also transform it—his works favour dark tones, distancing us from the materiality of facts in Favor of a more complex contact with reality, because, coupled with human experience, it sometimes distances to bring us closer. The great difference between classical and modern is that for Da Vinci, the structure of reality lies in the world, and for Cézanne, it lies in experience. It is difficult to unravel, in perception, the thread that connects it to reality, escaping arbitrary fantasy.

Perhaps this is why, in some works, he incorporated the image of the portal and the promise of the afterlife, in the curved branches that intertwine in thin thresholds and in the apple tree, an ancient symbol of paradise. But his portals do not lead us elsewhere: the door is destiny itself. Glory is not reserved for the afterlife but is present now; it is we who fail to see the shreds of paradise in all things. If the Gothic style intertwines branches in transcendent vertices, Moth bends them downward to reveal to us this immanent paradise that is perceptive maturation. The Greek golden rule was also the revelation of perfection in matter, and the shells of Force Fields, so often the symbol of a perfect writing that guides the forms of the cosmos, allude to it. But here, the holograms that enclose them impede the objectivity of a clear perspective, thus playing with the multiple points of view that make up our subjectivity.

To assume an absolute alliance between language and reality is to believe not only in an existence entirely accessible to humans—also in our capacity to articulate it. But our experiment is more of a kaleidoscope, too vast to be understood. There is always something that escapes the nexus of discourse. We find ourselves, it seems, between imprecise languages and fleeting realities. The essential, as Wittgenstein said, is inexpressible: "Whereof one cannot speak, it is better to remain silent."[5] Realism is not the arrogance of easy certainties, but a lucidity in the face of the uncertainties and unknowns of a life whose essence, if not clarified, can nevertheless be suggested by art as a total experience. The attempt to express the inexpressible is right, elucidating without determining—instead of an escape that feeds false senses of freedom, a maturation that expands reality. Under the mirror of consciousness, the eye widens, not knowing if what it sees is a reflection of itself.

The exhibition Vivenciar is on display at 3+1 Arte Contemporânea until the 26th of July, curated and written by Caroline Hancock.

[1] Lispector, Clarice. (2009). A Paixão Segundo G.H.. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, p. 19.

[2] Graves, Robert. (1997). The White Goddess. London: Faber and Faber Limited, p. 33.

[3] Graves, Robert. (1997). The White Goddess. London: Faber and Faber Limited, p. 18.

[4] Graves, Robert. (1997). The White Goddess. London: Faber and Faber Limited, p. 19.

[5] Wittgenstein, Ludwig. (1980). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, p. 203.

BIOGRAPHY

Tomas Camillis is an author and researcher based in Lisbon, working on fiction and on essays in the interplay between art, philosophy and literature. He has a master's degree in Art Theory by PUC-RJ. In recent years he has participated in researches, taught courses in cultural institutes, helped organize conferences and published in specialized magazines. He currently collaborates with the MAC/CCB Educational Service and Umbigo magazine.

ADVERTISING

Previous

article

15 Jul 2025

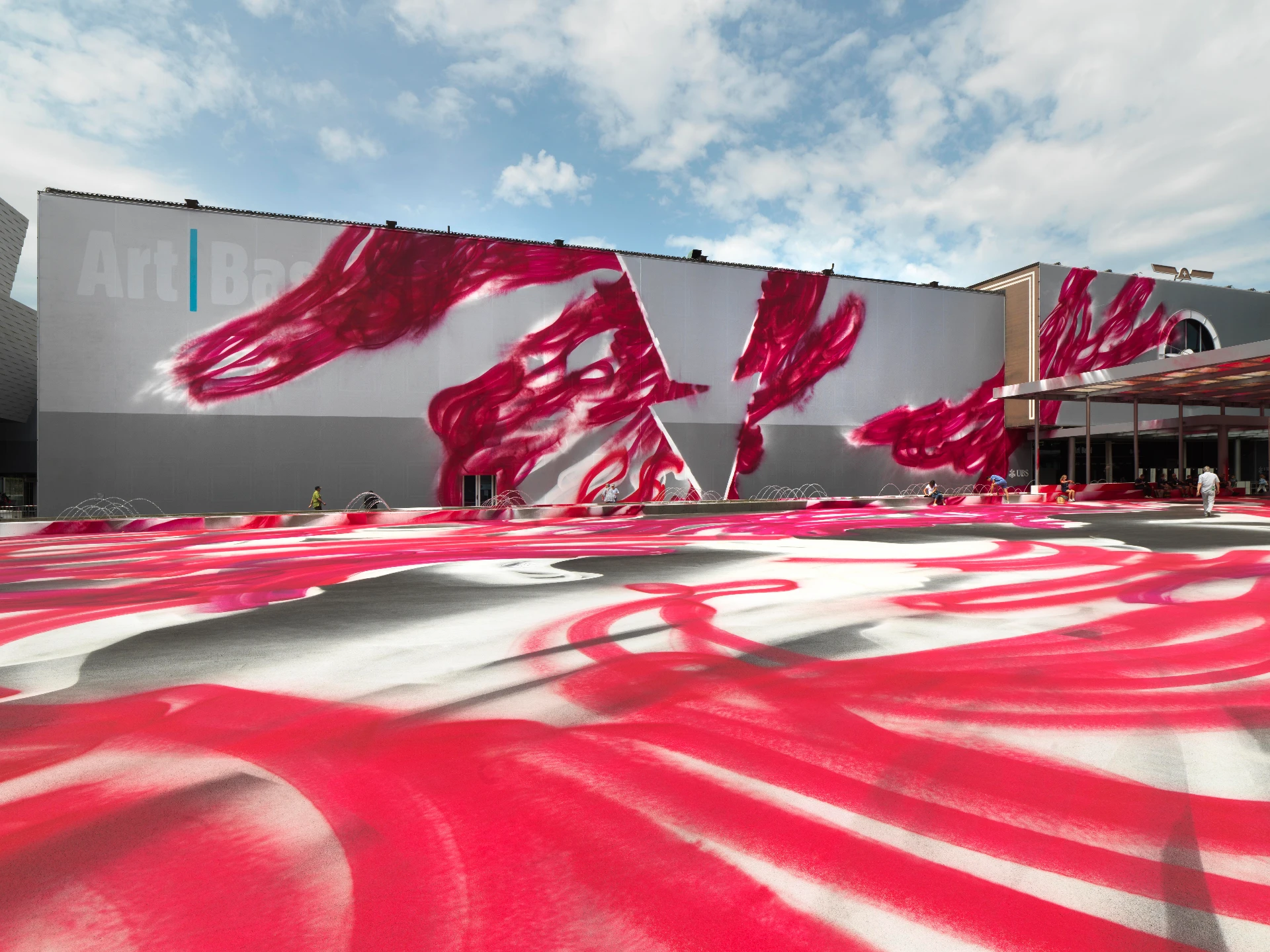

The Art World, at Basel Art Week. Which world do we seek?

By Benedita Salema Roby

Next

agenda

16 Jul 2025

Umbigo #93 - Regeneration

By Umbigo

Related Posts

[A] Guilherme Parente, [L] FCC-bj2nj.jpg)